Modal Progressions

Thinking about musical notes the way a painter thinks about color choices.

A Few Thoughts on Modal Music

I talk a lot about modes and how to use them effectively. A few previous articles I posted like “Borrowing Musical Structures” and “Scales and Modes are the Same Thing?” talk about concepts like “Parallel Scales/Modes”. Parallel simply means that we are using scales and/or modes that all start on the same note. Having the starting point is a great way to compare and contrast notes that come after the first one.

Before we jump into modes, I’d like clear my head by talking about how modes are often neglected. When I was first learning about modes it was in a college class and I memorized what I had to for the sake of passing tests. I don’t count that as learning because it was a bunch of numbers and letters. It wasn’t until later in life that I began to embrace modes and really try to learn them as tools. When that happened, my musical abilities sky-rocketed. Modes made every other concept easier because of a few “rules” that I came across.

All modes are their own “scale” because they have a formula, which is a set of numbered degrees that describes the notes used.

They create basic chords by using every other note in that mode, which can be applied within that mode AND within other modes.

They have Tritones (pronounced “Tri” - “Tones”), which are intervals of three whole steps that cause tension. This kind of tension acts like someone pointing you in a direction. If you use a Tritone, then you get pointed one way or another. If you don’t use a Tritone, then there is no direction to consider. Both have their uses.

They act like puzzle pieces. Each mode has its place with the grand scheme of things. The beauty of these puzzle pieces is that you can turn them and find many ways to let them fit. We’ll be turning quite a few pieces in this article.

And now for the big one…

Modes are NOT something that happens to overlap with a scale. They ARE tools that help shape sound the same way an artist mixes paint.

That last one is big bullet point for me because there are so many videos and articles out there that try to explain modes in a simple way so people can begin to understand them. I’m guilty of that as well. Modes can be hard to grasp because there are so many overlaps. For examples, the Ionian mode uses degrees 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. The Lydian mode uses the same degrees but with a ♯4. The Mixolydian modes also uses the same degrees as Ionian, but the seventh mode is a ♭7. You might not think that slight changes would make a big difference, but they are everything when mixing musical colors. So let’s jump into modes so you can see the variety they provide.

Major, Major, Major…

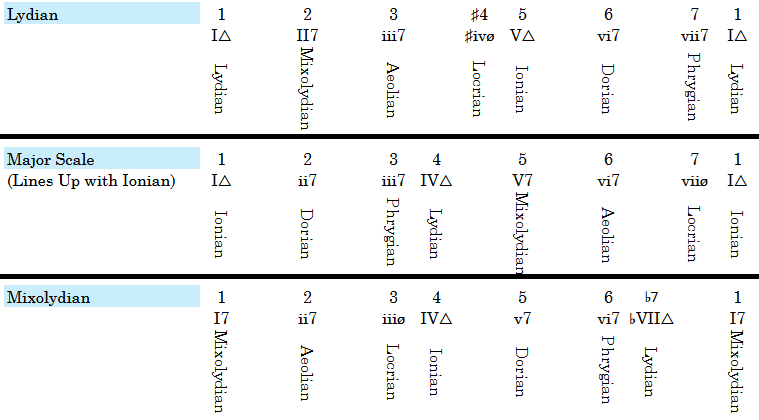

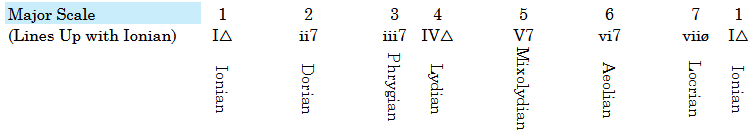

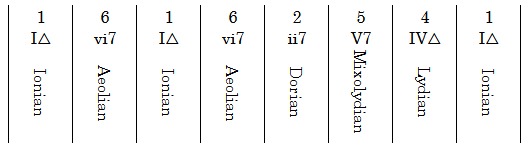

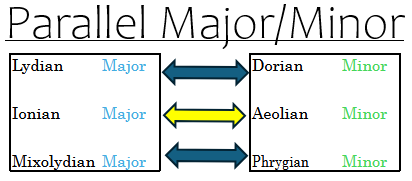

Above I have the three major modes: Lydian, Ionian, and Mixolydian. Each has their degree numbers, roman numerals for tetra chords (4 note chords), and relative modes associated with each degree with the major modes.

Instead of calling Ionian by that name, I’ll call it the Major Scale because we will be using that scale as the primary scale for all three modes. In other words, “THE MAJOR SCALE” is the framework for what we play in any “Major Context”. Lydian, Ionian, and Mixolydian are modes we can turn to that all line up with the Major Scale because they use the degrees 1, 3, and 5. The remaining degrees are what helps us shape our sound as we construct a song. So the Major Scale is the frame, and the three modes are pallets of color.

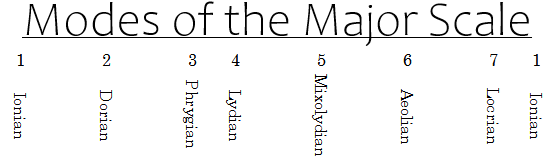

The basic way of learning these three modes is that Ionian starts on the 1st degree of the Major Scale, which is true since they line up perfectly. Lydian starts on the 4th degree of the Major Scale, and Mixolydian starts on the 5th degree. Look at the order of modes within each horizontal strip and you’ll see the same pattern of Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, Locrian, and back to Ionian.

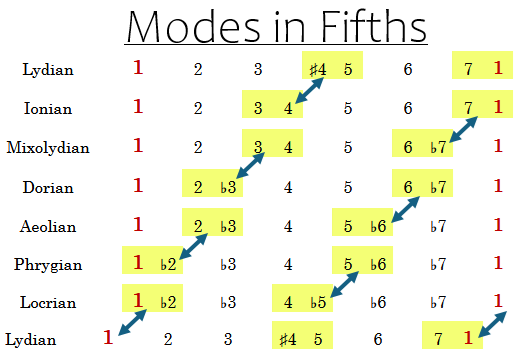

But that’s not what makes modes special. I’ve organized the above chart so that Lydian with its ♯4 or “raised 4th” is above Ionian, while Mixolydian with a ♭7 or “lowered 7th” is below Ionian. This is how you should be organizing modes, because it connects key changes in a variety of ways.

Reorganized Modes

Yes, the above order is what we play from each degree, but that keeps you in one key. Even if we play in another key with a mode like Lydian, we stick to seven notes and seven basic chords. That’s boring because all we’re doing is painting with seven colors that can only add up to a limited number of mixtures. Since there are twelve total notes, it sure would be nice to mix in some of those missing five notes with a starter set of seven. Here’s how.

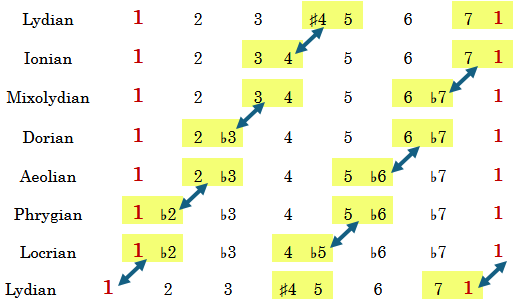

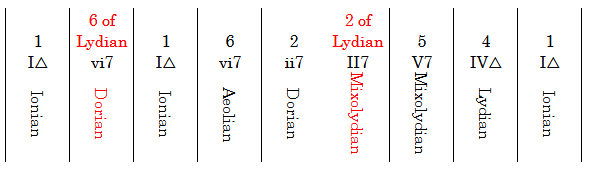

Above we have the modes organized in “fifths”, which is to say that they line up with the Circle of Fifths. The half-step intervals are highlighted in yellow and changes between each mode are shown by arrows. Sticking to the major modes, we can start on Ionian and change either the 4th or 7th degree note to access Lydian or Mixolydian. That simple concept is how we can figure out what to play over chord changes.

Let’s say we playing a Major Scale song in any key and see that only one note has been raised or sharpened. That’s a great clue that we are using notes from the next key over on the Circle of Fifths in a clockwise direction. Let’s also assume that the chord we are playing over should be the sixth chord. The sixth chord in a Major Scale starts the Aeolian mode, but by sharpening one note we are likely sharpening the key. That means that we can use the above order of modes and see that Dorian is right above Aeolian. So for this key change we play that mode. Now the formulas mean something! We can play Aeolian with a ♭6, but since we sharpened the mode we should use a ♮6 (natural 6th). If you practice your scales in terms of degrees, then finding a ♭6 or ♮6 is a lot easier than trying to find a specific lettered note. I mean, who wants to play D Aeolian and memorize every technical lettered note when you could just count to seven and learn about the ♭ and ♯ variations?

Putting It to Use

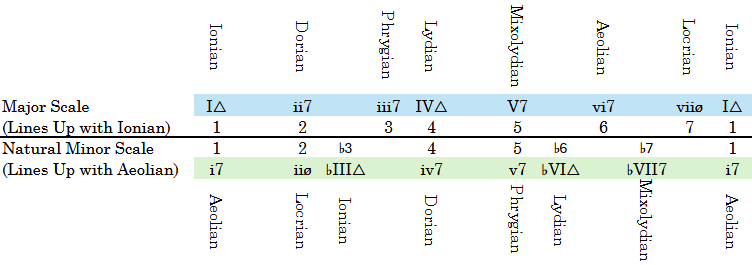

So lets give it a go! Above is the same set of major modes for reference. Below are two progressions of chords with the associated modes that fit them. Think of each bar line in the same terms of a bar line using a 4/4 timing. The first progression is a vamp, or back-and-forth, between the 1 and 6 chords for the first four bars. The last 4 bars takes us through a standard movement of 5-to-1 from the 6 chord to the 2 chord to the 5 chord. This means that if we are in C Major Scale, Am is the 6 chord, Dm is the 2 chord, and G is the 5 chord. The note A is the fifth degree of D and D is the fifth degree of G. That’s what sets this up in 5-to-1 movements. G is also the fifths degree of C, but instead of jumping to the Tonic chord, we stop by are the 4 chord to mellow things out. This can be played in any Major Scale because the degrees of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 are always used.

The second progression adds in some of the Lydian mode. The first change is when Dorian is substituted in place of Aeolian. Both modes use a m7 chord, so the harmony remains the same. The change is on the ♭6 of Aeolian. Dorian has a ♮6, so using that changes the tonality and tension for brief moment. We’ll get more into tension soon.

The next change is when we keep Dorian as the 2 chord, but we split the bar up with a brief II7 chord that uses Mixolydian. This time we still change the same note that we used in altering Aeolian to Dorian, but now the harmony is changed as well. A dominant chord like a II7 leads us a fifth to a V7 perfectly because dominant chords work great in 5-to-1 movements. A II7 to V7 makes the 5 chord a little stronger, but it still gives way to the 4 chord and then ends on the 1 chord.

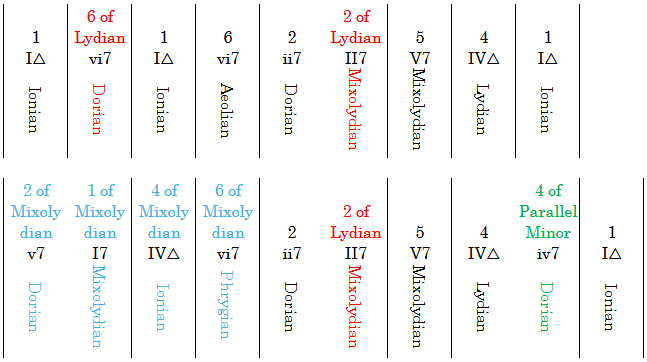

Adding in Parallel Minor

Whenever we are in a Major Scale, we can mix in the parallel Minor Scale. In other words, the Major Scale is still our primary framework, but we can pull in some laid-back Minor tonality to add to our sonic colors. Below we have the Minor Scale with a ♭3, ♭6, and ♭7. Notice how this lines up with the Aeolian mode and how each change in modes skips two modes when we think about the changes in terms of “modes in fifths”. That order is Lydian, Ionian, Mixolydian, Dorian, Aeolian, Phrygian, and Locrian. Below we can start on the 4 chord with Lydian, skip both Ionian and Mixolydian, and arrive at Dorian to get a mode out of Parallel Minor. The same is true for each mode. For example, the 2 chord in Major Scale is Dorian. Skip over Aeolian and Phrygian, and you’ll get Locrian.

Now to mix in all of these great colors!

Below is the same progression as before, but with a second movement. This time we take a quick detour through Mixolydian to use a Dorian 5 chord, Mixolydian 1 chord, and an Ionian 4 chord. This makes the 4 chord feel like its 1, but hang on as we move into a Phrygian 6 chord that is still a m7. That still moves perfectly to a Dorian 2 chord from our main Major Scale. We then repeat the end of the first progression with a little twist. Instead of a standard 4 chord to 1 chord to mellow things out, we take a 4 chord in Lydian and briefly modify it to be a m7 Dorian chord. This is where our parallel Minor Scale comes in. This takes a mellow 4 to 1 and turns it into a “minor 4” to 1 and adds an extra layer of mellow on top of mellow. It’s like having a campfire on a cold day and then adding in a fuzzy blanket.

Boiling it All Down

Here’s a quick recap of this big concept.

#1: The modes of each degree of the Major Scale are as follows.

#2: Learning your modes in “fifths” along with their degree formulas gives you access to key changes and modal movements.

#3: Major modes work with the Major Scale, which can borrow from Natural Minor. Minor modes work with the Natural Minor Scale, which can borrow from the Major Scale. Locrian is tension and directing your ear toward another mode.

#4: Each Major mode is paired with a Minor mode. You can think of this as Lydian and Dorian are the two sharpest modes, Mixolydian and Phrygian are the two flattest modes, and Ionian and Aeolian are balanced in the middle. This balance is what make Ionian/Major Scale and Aeolian/Minor Scale our main frameworks for music.

And there you have it. I know this is a lot, but don’t worry. We’ll work on this a bit more in the next article. If you have any questions, let me know with a comment.