Scales and Modes are the Same Thing?

Taking a quick look at the relationship between scales and modes.

Addressing the Problem

When people starting learning about a concept known as “modes”, they tend to think of a mode as “an interpretation of a scale”. I know, because I did this for a long time. To better understand this, let me go over what a scale is in basic terms so that you don’t have to have a strong knowledge of music to get it. To get started, I’ll use quotes to help focus on key aspects of scales and modes.

Any “Major Scale” can be thought of as the seven notes sung as “do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti” and “do” again. If you can understand “do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do”, then you already have a basic understanding of a scale. A mode is when you start on any of the seven notes and sing from that note to itself again. For instance, the “First Mode” of a Major Scale is “do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do” because it starts on the first note of “do”. The “Second Mode” of the Major Scale starts on “re”, so the notes are “re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do, re”. Each of the seven modes starts on a different note, but uses the same notes.

That’s where the pitfall comes in. Since each mode uses the same notes, many people think that there is no difference between scales and modes when first learning about modes. To make the difference obvious we can look at this from the terms of “degree number” and “interval distance”.

Degrees Give Space

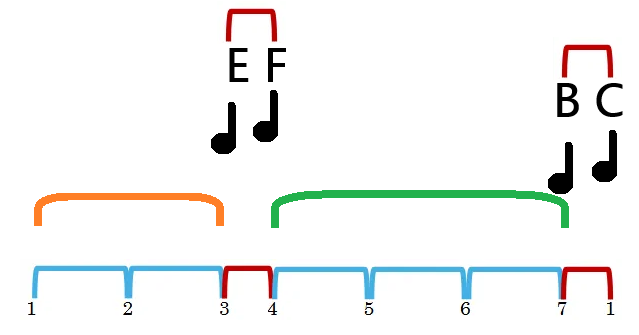

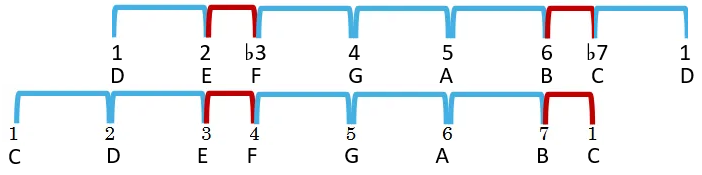

Let’s redefine the Major Scale for a moment. Instead of sounds, we can use the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. In previous articles I’ve pointed out that each degree represents a note and that all notes are a whole step apart EXCEPT for the intervals from 3 to 4 and 7 to 1. Below is a chart to help see what I mean. Notice that degree notes 3 and 4 are right next to each other. The same goes for 7 and 1. All other notes have a little space between each other.

When looking at the degrees and the way each interval creates space we can see that the half-step intervals (in red) from 3 to 4 and 7 to 1 break up the whole steps (in blue). This creates a “shape” that our brains can understand. You don’t need any musical background to understand the sound of a scale. In fact, if you play just the four half-step notes (3, 4, 7, and 1) then you will give enough sonic information for your brain to know which note is which.

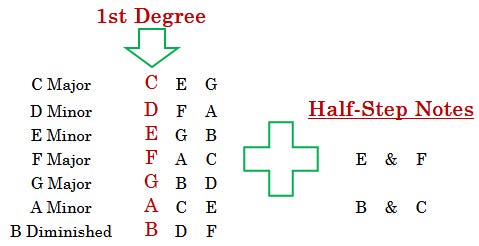

To put this to the test, try playing the notes E & F along with B & C. Doing this effectively sets your brain to expect C to feel like it is the 1st degree note. This is because there are two whole steps from 1 to 3 and three whole steps from 4 to 7. Your brain is constantly trying to make sense of everything it experiences. By giving your brain four frequencies, it automatically relates them using your auditory language abilities. Just like the upturn in frequency when someone’s voice asks a question, the relationship between frequencies gives your brain context.

Below is a visual representation of this. Your brain hears E, F, B, & C AND organizes those frequencies. It then also knows that there is a two whole step space (in orange) and a three whole step space (in green). That’s all it takes for your brain to understand that the only way to make these four notes work is if C is 1. The remaining notes come after that as E is 3, F is 4, and B is 7. These notes cannot fit into the Major Scale in any other way.

Back to the Problem

The next issue occurs when a mode uses the same notes of a scale. If you play the notes “C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C” followed by “D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D” then it is easy for your brain to compare these two sets as the same thing. And why not? They’re both the same collection of notes.

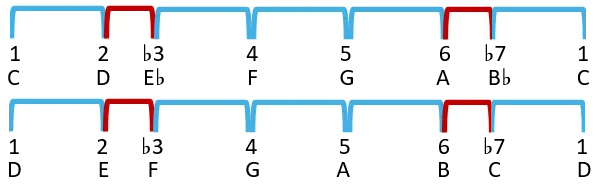

To hear the difference we need to give our brains context. This time we are going to play the notes C, D, E♭, F, G, A, B♭, C. Two notes went flat. This allows this scale to start on C, but use the degrees 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, 6, and ♭7.

After playing C, D, E♭, F, G, A, B♭, C for a bit we can then play D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D and hear the same overall sound. Below is what happens. We hear both collections of notes as relatively the same thing because they “use the same degree numbers”.

Now that we have this “♭3 and ♭7” sound in our ears, we can compare it to the C Major Scale by playing “D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D” followed by “C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C”.

Too Much Information!

The next issue in understanding modes is when we play all of the notes, which we just did. Oh, boy!

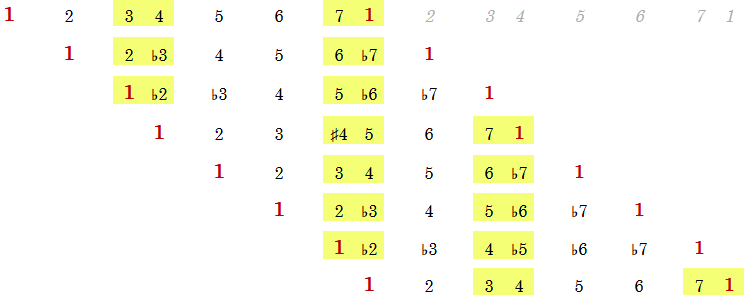

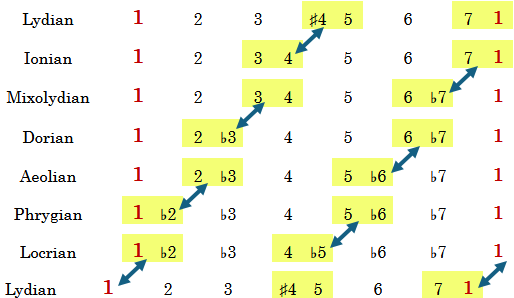

Instead of playing all seven notes, let’s focus on the two half-steps and the 1st degree. Below are all of the modes of the major scale with these notes highlighted so your can visually see the sonic spacing.

Instead of playing C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C starting on each note AND playing all of the notes. Start with C, then play E & F and then B & C. Then play C again. This will let your brain hear the half-steps relative to C as the 1st degree note.

Next play D, then play E & F and then B & C. Then play D again. The same process can be repeated with E even though it is part of the half-steps. Play E, then play E & F and then B & C. Then play E again. Its simple, but your brain is powerful enough to start absorbing new information and hear the little differences.

Harmonized Information

Now we can play chords associated with each mode. The way we construct chords is by starting on a note and playing every other note. So a C Major chord uses the notes C, E, G. A D Minor chord uses D, F, A. Below are the chords in the C Major Scale. Play each one with a mindful focus on the 1st Degree note. Then play the half-steps of E & F and B & C. Then play the chord again. This gives your brain a little more sonic information and let’s you feel the half-steps a little bit more.

Parallel Processing

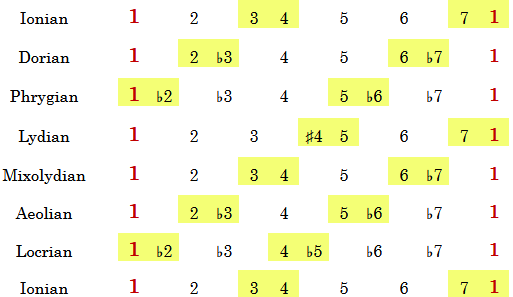

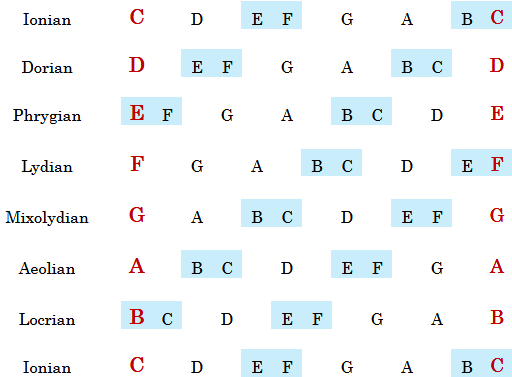

This whole time we have been playing “Relative Modes”. This means that each mode uses the same notes, therefore they are directly relative to each other. The modes of the C Major Scale are shown below by degrees and letters. I’ve included the names of each mode as well. Think of each mode as having a “formula”. The Ionian mode lines up with the Major Scale by using degrees 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. Skipping down to Lydian we see that the only difference is a ♯4.

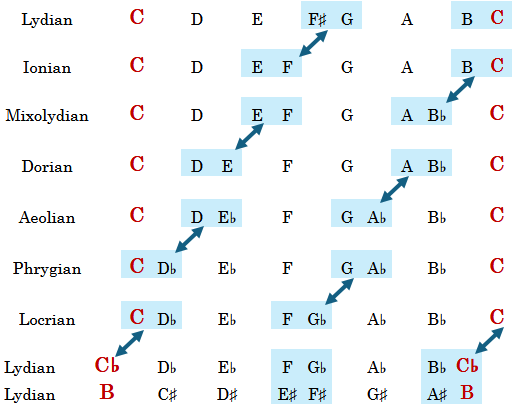

Above we can see that each mode is very different from the previous one. So let’s put them into “Parallel Order”. Parallel means that we start on the same beginning note, which we’ll use C as that note.

Each mode is only one change away from two other modes. For example, raise the 4th degree of Ionian to get Lydian. Or you can lower the 7th degree of Ionian to get Mixolydian. Playing each mode starting with C will give your brain another set of context to use in hearing the sound of each mode. You can also use chords with these modes. In C Aeolian, the chord C Minor uses the notes C, E♭, G. Play that chord and then the notes in C Aeolian and you’ll definitely hear a change from C Ionian to C Aeolian. A harder change to hear could be from C Dorian to C Aeolian. The difference between these two modes is the 6th or ♭6th. Play a C Minor chord and then focus on the note that make a 6th or ♭6th: A and A♭. That one change makes a world of difference.

By the time we get to the bottom of the list with Locrian, we can lower the 1st degree to get Lydian again. Lowering the note C can create a C♭ or B depending on which scale works best. For now, just focus on the slight changes that alter each mode, which are show by the arrows above. Keep working on comparing and contrasting modes with a focus on Degree Numbers and the next article I post will be very useful.