WHAT IS LYDIAN?

Lydian is the fourth mode of the Melodic Major scale and has many similarities to Ionian. Lydian can be described as mystic or the sound of outer space. I tend to think of it as the calm after the storm. There’s a bit of tension that makes this otherwise bright major mode more of an unending thought. Just like with the end of any storm, there is a sense of relief. What Lydian does to that relief depends on how the fourth degree is used or restrained. Lydian can give you a mellow yet bright feeling after the storm, but the fourth degree of Lydian can leave as many branches in the road as you like.

While Ionian uses all natural degrees (no sharp or flat degree numbers), Lydian has a sharpened fourth degree. If you are not familiar with Lydian, then you may be tempted to call the sharpened fourth degree (#4) by a different name; the flat five (b5). This would be incorrect because Lydian has a fifth degree, and we cannot have two degrees with the same degree number. This does not mean that our fourth note has a sharp in its name. Only the degree position is sharpened. Below are the chords used for Lydian in the key of C and the key of G. Notice how each key uses each letter only once and that the only sharp note used in either key is the note F# in C Lydian. If you want to know more about note naming conventions, then check out my posts on the “Circle of Fifths” and “What Key I Am In?”

What we can first do with Lydian is focus on the interval between degrees 1 and #4, which is a TriTone. You may have noticed that I spend a lot of time talking about TriTones. That's because I find that most musical topics skip the TriTone for several reasons. I believe that skipping such a strong interval weakens a person's ability to learn musical concepts because the TriTone is ever present in all of Melodic Major’s modes. By knowing how to use it or avoid it can make a huge difference and Lydian is no exception. The TriTone interval from degrees 1 to #4 does a lot to create tension, brightness, and motion within this mode.

For the sake of these examples, I'll use the key of G because it gives up C Lydian, which in turn has F# as our #4. This can help make things easier to understand since the #4 note is F#. All the other notes as shown in the chart above for C Lydian (in the key of G) are natural, just like the degree numbers, so our fourth degree and fourth note are both sharp for convenience.

THE SUSPENDED #4

Lydian is a major mode because it uses the degrees 1, 3, and 5. It is not a dominant mode because it has the major seventh degree (7) and not the dominant seventh degree (b7). We can also use a suspended second chord (sus2) by suspending the third degree down to the second degree. In C Lydian a Csus2 uses the notes C, D, G. We do not have a standard suspended chord, notated as sus or sus4. Instead, we have a sus#4. In C Lydian this would be Csus#4 which uses the notes C, F#, G. This chord is not commonly used due to the TriTone interval from C to F# combined with a minor second interval from F# to G, but it has a lot of tense usage.

I could play C to Csus#4 and use the #4 note to lead into F#m7b5 to then lead to Em. It's an interesting way-point from C to Em with a touch of voice leading. I could even go in reverse and start with Em and go to F#m7b5 followed up with Csus#4 balancing back to a C major triad. Here's audio examples of both motions.

CROSSING THE FIRST OCTAVE

Things changes when we take the #4 and place it in the second octave. In the second octave all the odd numbered degrees retain their numbers, but all the even numbered degrees get seven added to them. Two becomes nine, four becomes eleven, and #4 becomes #11. Renumbering these degrees makes a lot of sense because the even numbered degrees function differently beyond the first octave. With that said, the #11 degree in C Lydian is still F#, but the distance of an octave plus a TriTone from C to F# causes the #11 to fall in a special place.

We build standard chords in alternating thirds. Building a major chord starts with a major third and is followed by a minor third. Starting at C we have the notes C, E, and G. By adding another major third, then a minor third, and repeating we can get the notes C, E, G, B, D, F#. These notes correspond to the degrees 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, #11 and are naturally occurring when building a major chord. This means that a #4 causes its own form of tension as it is out of the set of naturally occurring degrees, while a #11 belongs to the natural order of alternating thirds within a major chord and give a sense of brightness and balance.

We can also use major chords that contain the seventh and/or the ninth-degree notes to make the #11 to 1 TriTone feel more at home. Chords in C Lydian that use this concept could be CMaj7 #11 (C, E, G, B, F#), C add9 #11 (C, E, G, D, F#), D6/C (C, D, A, B, F#), or CMaj7 #11 no3 AKA F#sus4 b9/C (C, F#, G, B, F#). All these chords use only what is available from the chart above and give great Lydian sounds that you can use to transport yourself to through a bright patch in your arrangements.

USING THE LYDIAN SOUND IN A PROGRESSION

There are so many ways to use Lydian's #4 or #11 sound to accent little moments in your compositions. A standard way is to just play the #4 or #11 note in a melody when your song uses the Lydian chord. You can be in Phrygian and make this work for you by playing Em followed by FMaj7 with a B note in the melody over that FMaj7 chord. If you use B in the first octave from F, then you have a #4. Otherwise, it is always a #11. From there you can continue with your Phrygian song or progression and that brief moment of using the note B against a root note of F will be a great accent in the storytelling of your piece.

Another perfect fit is to use the #4/#11 in the four-chord of a plagal cadence. A plagal cadence is where you end part of a song by going from the major Sub-Dominant “four chord” to the major Tonic chord (IV to I). In G Ionian the fourth degree starts the C Lydian mode, so you can play C major to G major or Csus2 #11 (C, G, D, F#) to G major. Doing so will let you use the TriTone interval between the notes C and F# in a non-dominant fashion.

To be specific about this, the “four-chord” is normally a Pre-Dominant chord that leads to a Dominant chord that then leads back to Tonic. Pre-Dominant chords contain the fourth degree of a scale or mode, while Dominant chords contain the fourth and seventh degree which is all that is needed to create a TriTone interval. In the next example, we use a TriTone interval in a Pre-Dominant position to create a Dominant feeling. You can do this with any Lydian chord that includes the #4 or #11 because the TriTone is built off that degree and the first-degree notes. Here's an audio clip for a Lydian plagal cadence.

RESOLVING TO LYDIAN

Ending a song on a major chord with a #4 or #11 can be a challenge if you're just sticking the #4/#11 note in there. That good old TriTone wants you to move on to something that feels more like a Tonic rather than a Tonic with a TriTone interval. Whether that Tonic is major or minor makes little difference granted that the TriTone gets resolved. To combat this and make the Lydian sound feel at home we need to make sense of the #4/#11 through context.

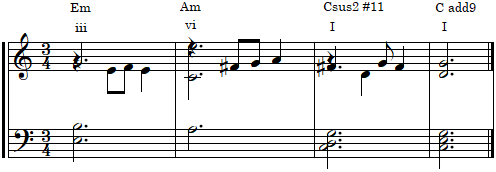

A simple way of doing this is to use a chord like Csus2 #11 (C, G, D, F#) because it is a suspended chord that can easily move to a C major triad. We can also follow the Csus2 #11 with a C add9 (C, E, G, D), which is basically the same chord with the note D added as the 9th degree to retain the note D that we suspended. Playing an add9 chord also keeps a sense of brightness. This is important in Lydian because the #11 adds brightness and tension. By dropping the #11 and switching to the 9th degree we can let the tension go while keeping some brightness. Here’s a simple example that resolves this way in ¾ time.

EMBRACING THE ROOTED TRITONE

Now you may want to keep that rich Lydian sound at the end of a song for a lingering sense of unending. To keep the TriTone from wanting to pull you elsewhere you'll want to continue to focus on context. The first step is to end with a #11. This will keep any major Lydian chord in a naturally balanced state. You could be bold and focus on the 4#, but there is enough tension in the #11 and this is just an example. The next thing to do is to lead with structures (chords or melodies) that progress toward the #11 note. In this example we'll stick with the key of G and the C Lydian mode. Our #11 note to focus on is F#.

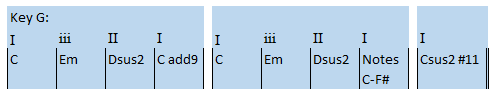

I'll start with C (C, E, G), Em (E, G, B), Dsus2 (D, E, A), and C add9 (C, E, G, D). This progression of I, iii, II, I allows the root notes to step up from C to E and then walk down our scale back to C. The other thing it does in include the note E in every chord. Then I'll follow this up with the same progression, but the C add9 will be replaced by a Csus2 #11 (C, G, D, F#). The effect this causes is a gradual rise from E toward F# until we are throttled into F# as our #11 note. To spice this up I’ll play the notes C and F# as a dyad (two note chord) using degrees 1 and #4 right before playing the Csus2 #11. I’ll keep the note F# at the same pitch throughout the end so that the #4 tension is replaced with #11 brightness, but the note that creates both the #4 and #11 are the same pitch. This will create a strong sense of unending. Check it out below.

THE LOCRIAN-LYDIAN SLIDE

I going to be honest with you. I just came up with the name for this because the “Locrian-Lydian Slide” is how I use this next little oddity. The way it works is by understanding the modes in fifths. Check out my post on “The Modes As A Family Of Scales” for more detail. For this example, I’ll start by comparing Lydian to Ionian. Lydian has a #4 degree and to transform Lydian into Ionian all we need to do is flatten the #4. Then we would have all natural degree numbers. We can transform one mode into other modes by making a change to a single degree at a time. This is easier to see when we order the modes in fifths.

We can use these single degree changes to take Lydian and transform it into Locrian by sharpening Lydian’s first degree. I know this sounds completely out of bounds, but music theory is all about finding ways to bend or break the rules. By sharpening the first degree we get an odd set of degrees: #1, 2, 3, #4, 5, 6, 7. We cannot have a #1 no matter how hard we try so to fix this we flatten every degree in our odd set, which becomes 1, b2, b3, 4, b5, b6, b7. This is the Locrian mode. But how do we use this? Well, we try to find some way to play a melody the transforms from Lydian to Locrian or the other way around, but that may be too much an academic exercise than a practical example.

What I like to do is play a half-diminished chord as my bii chord in Lydian. In C Lydian this would be Dbm7b5 to CMaj7. Essentially, I am taking a Lydian chord like CMaj7 and I am sharpening the first degree to raise just the note C to Db. The resulting chord is a Dbm7b5. This chord doesn’t belong diatonically, but we're just borrowing the note Db from a parallel mode. If you want to know which mode, then think of going from a major mode starting at C, like C Lydian, and going to a minor mode that also starts at C, like C Phrygian. The parallel mode of C Phrygian has a DbMaj7, but we are only borrowing the note Db to create a temporary Dbm7b5.

Here are some chord progression examples that all use the key of G. Try them out with any timing or personal modifications as you see fit.

HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT

This next part may be a bit advanced, but I believe it’s usually best to go for something difficult from time to time. This way we can learn something from a challenging subject and, while we may not grasp it entirely, we can begin to become familiar with the topic.

In my previous article on the Phrygian mode, we used Lydian off the bII degree and Dorian from the bVII degree. In the key of C we have D Dorian, E Phrygian, and F Lydian. Well, if we go to our parallel modes, then we can borrow Db Lydian. This lets us do a lot between E Phrygian and D Dorian. Below is an audio example that uses this idea. I’ll list the chords and modes used, but I’ll let you listen to what’s going on so that you can hear how borrowing Eb Lydian gives access to a hidden sound that ties in perfectly.

LYDIAN METAL

A lot of what we’ve covered has to do with melody and harmony. These are always important, but my examples are usually from the realm of jazz. Since we can use any genre of music, I thought that we should try out a 90s metal example with some effects pedals. This will use the same basic format from before, but I’ll play a straightforward four chord progression. These will still be Phrygian’s i, bII, and bvii degrees along with the added VII degree, but we’ll use power chords (root and fifth degree only) and let Lydian come out over the bII and VII chords. I’ll also use the key of D so that we can fit the power chords in the lowest register of a standard tuned guitar.

I’ve added a pedal tone to carry over each measure with a phaser effect so it stands out a bit. The pedal tone note will help accent the mode used in the chart below. Each accent note is either the fifth degree of either minor mode (Phrygian or Dorian) or is the major seventh degree of Lydian. The melody will use the #4 degree for both Lydian measures, which can be incorporated with the minor modes.

Listen to the melody for F# Phrygian’s fifth degree note (C#) to become G Lydian’s #4 degree note (also C#). Then F Lydian’s #4 degree note (B) will become E Dorian’s fifth degree note (also B).

THANK YOU!

Thanks for reading. I really hope that my work helps you to find your own musical path. I'd love to hear from you and find out what has helped you. If there are any other topics or questions you would like me to cover, then please let me know in the comments. I also have a “Coming Soon” page to let everyone know what topics will be talked about and when they get posted as well as an my Music Theory for Everyone Instagram page.