A New Pallet Of Sound

When I first started learning the Harmonic Major scale, I was learning it as a completely new scale. This set me up for failure because I had no way of connecting this new scale to what I already knew in the Major Scale (aka Melodic Major).

I want to make Harmonic Major enjoyable and useful to you. To do that we’ll use what we know about the Major Scale and add in one more degree. This extra degree will allow us to add in chord structures that are not found in the Major Scale. It will also help us to create new tensions and resolutions to those tensions, which in turn helps us to expand our musical vocabulary.

Ultimately, I want you to be able to use Harmonic Major as a set of textures that can be added to your pallet of Major Scale sounds. If you are unfamiliar with some of the terminology used in this article, then check out previous topics in the Let’s Play Music series such as #2 Functional Harmony, #5 Connecting Chords with Modes, and #10 Putting Musical Pieces Together Through Analysis.

Embracing The Minor Sixth

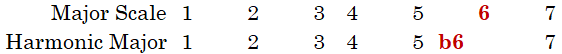

The Harmonic Major Scale uses the same degrees as the Major Scale, except for the major sixth degree. Instead, we have a minor sixth degree. This one change creates all the interesting aspects of Harmonic Major.

By not having a 6th degree, we do not have an Aeolian mode. Without this mode we no longer have a relative minor key. Think of the circle of fifths and all those major keys. Now think of it without a single minor key to use. We are now “stuck” with a tonal center that is major. We can no longer move to a 6th degree Aeolian sound because it simply doesn’t exist. This causes all the notes in Harmonic Major to focus on resolving toward the 1st degree note, which is what happens when we play in Ionian. To make better sense of this, let’s look at the charts below and compare the Major Scale to Harmonic Major.

Another way of thinking about this is through the circle of fifths. Many examples of the circle show the major and minor keys. In Harmonic Major there are only major keys. The minor key is equal to a major key’s 6th degree. Harmonic Major’s b6 literally flattens and removes the minor key.

When we use the Major Scale (aka Melodic Major) we have three major modes, three minor modes, and a diminished mode along with their corresponding chords. We have similar modes in Harmonic Major. The difference is the minor sixth degree (or b6). This degree is highlighted above in red so you can see how it “travels” through our modes. Notice how the altered degree in each mode is actually the same note. In this example I used C Harmonic Major. Since we have flattened the 6th degree we alter the note A, which becomes Ab. The note Ab also represents the altered degree in each mode, such as the b5 in Dorian b5 and the 1st degree in Lydian Augmented #2.

The Modes of Harmonic Major

Look at each mode of Harmonic Major. We can describe each mode using the same names we already have from the Major Scale along with one “altered” degree. From here on out we’ll be using the key of C in Harmonic Major, which uses the notes C-D-E-F-G-Ab-B. Watch for Ab to be the one note that matters in all our new chords and modes as I give some brief descriptions of these modes.

Ionian b6 is our first mode because it is the Major Scale with a minor sixth degree. We still have a Maj7 chord in this mode, but we also get access to an augmented chord. This augmented chord uses notes from Harmonic Major’s first, major third, and minor sixth degrees. Augmented chords are useful in that the notes in them are all root notes because the distance between each note is a major third. By having the exact same interval between each note we can treat them all as the root note and treat all augmented chords as “equal inversions” of themselves.

This causes a C+ chord with notes C-E-Ab to be inversion of E+ using E-Ab-C and Ab+ using Ab-C-E. If we play C+, E+, or Ab+ then we are playing inversions of all three chords at the same time. This is what makes the sound of an augmented chord so unique. Our brains are trying to find a pattern of intervals to understand C+, but the intervals are all major thirds so we can’t hear one root note. Instead, we hear three root notes. It isn’t until we hear the next chord or phrase in a song that we are able to make sense of what the root note really was. At that point we are hearing the resolution of the augmented chord in the context of one musical phrase.

Dorian b5 is our second mode and overrides the minor sound of Dorian with two diminished sounds. The first is the half-diminished structure using degrees 1-b3-b5-b7. The other is a fully diminished structure using degrees 1-b3-b5-bb7 where the bb7 comes from Dorian’s b5’s 6th degree as shown below.

Dorian b5 still has a major sixth degree, which is enharmonically equivalent to the bb7 (double-flat seven). This is how we get two main chords from one mode.

When we talk about fully diminished chords like D°7, we are using another chord this is made of all root notes. Like the augmented chord, D°7 (D-F-Ab-B) is equal to F°7 (F-Ab-B-D), Ab°7 (Ab-B-D-F), and B°7 (B-D-F-Ab).

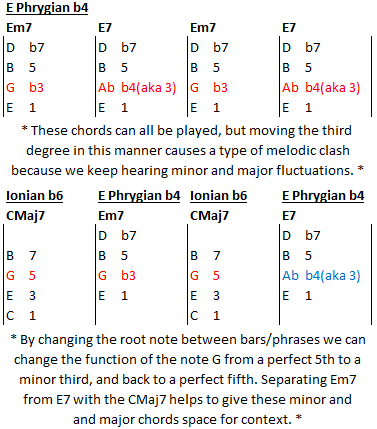

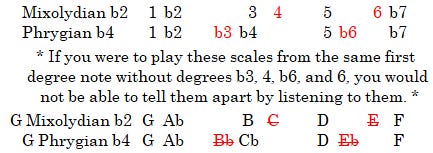

Next up is Phrygian b4. What the heck is a b4? It’s basically the enharmonic equivalent to a major third. This allows us to use chords like Em7b5 and E7 in the same mode. The catch is that Phrygian b4 melodies that use degrees b3 and b4 in a single phrase tend to sound “wrong”. This is because they use b3 as the minor third and b4 as the major third.

The “third” defines scales, modes, chords, and melodies as being major or minor. Having both options in Phrygian b4 is great, but they need to be separated in some manner. Try playing Em7 b11 (E-G-B-D-Ab) to E7 b2 (E-Ab-B-D-F) to C (C-E-G-C). The Em7 b11 puts the major third in a higher octave, so it functions as a b11 rather than a b4 or 3rd. The E7 b2 uses the notes B-D-F to create a Bmb5 that leads perfectly to C. E7 b2 also has the notes E and Ab. The note E leads to itself in the chord C (C-E-G) and Ab leads down a half-step to G in the same chord giving it the feeling of a “melancholy plagal cadence” of III/I instead of IV/I.

Don’t forget about the E+ chord as an inversion of C+. Playing C (C-E-G) to C+ (C-E-Ab) to E7 (E-Ab-B-D) to E+ (E-Ab-C) and back to C (C-E-G) is a great way of using C+ and E+ as equal “way-points” between C, E7, and C.

Our fourth mode is Lydian b3 or Lydian Minor. This mode takes the major third and flattens it to a minor with some extra flavor found in the major seventh. FmMaj7 (F-Ab-C-E) has the sound of spy movies and rainy day jazz café tunes.

But this is a type of Lydian mode, so we can’t forget about the #4/#11. FmMaj7 #11 (F-Ab-C-E-B) has a minor third note (Ab) and #11 as an enharmonic equivalent note to b5 (B). This creates a diminished feeling in the chord that calls for resolve to a chord like C (C-E-G). We can increase the tension by also playing F°7 (F-Ab-B-D). Again, the note D in F Lydian b3 is the major sixth, but this is equal to a bb7. This means that Ab as the #4 and D as the 6th can be treated as the b5 and bb7 found in F°7.

Also keep in mind that F°7 is equal to D°7 from D Dorian b5, so we can play Em7 (E-G-B-D) to Dm7b5 (D-F-Ab-C) to F°7 (F-Ab-B-D) and then to C (C-E-G) as a way to slowly increase tension until we resolve it to C.

The fifth mode is Mixolydian b2. This is the first mode that made sense to me when I started learning Harmonic Major. G Mixolydian b2 still has G7 as the V chord. The b2 simply adds tension that leads either with G7 to C (V to I) or in a melody with Ab leading down to the note G.

We can play G7 b9 (G-B-D-F-Ab) to C (C-E-G) and it works great as way to increase the tension before resolving to C. We can also use G7 b2 (G-B-D-F-Ab) to G7 (G-B-D-F-G) to C (C-E-G), which resolves the tension early so that we can use Ab as a tension note, but only for a brief accent.

Another way to think of this mode is to look at Mixolydian’s relative minor: Phrygian. The Phrygian mode’s b2 degree is what gives it that deep and tense sound. By absorbing the b2 into Mixolydian we get a dominant mode with a touch of that deep Phrygian flavor. It’s almost like Mixolydian b2 and Phrygian b4 are close cousins due to being dominant modes with a b2nd degree. If you played Mixolydian b2 without using the 4th and 6th degrees, then what you play could sound like Phrygian b4. It isn’t until you commit to a 4th, b6, 6, or even a b3 that we can be sure which mode is being used.

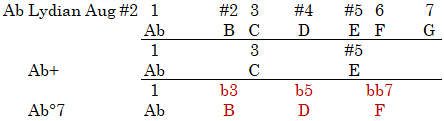

The next mode is where things get a little crazy. Lydian Augmented #2 has no major or minor qualities. Instead, we get chords like Ab+ (Ab-C-E) and Ab°7 (Ab-B-D-F). This is made possible through multiple enharmonically equivalent notes.

Since Ab+ and Ab°7 are equal to their augmented and diminished inversions, we gain access to every mode that uses augmented and diminished chords. Looking at the main chart at the top we see that Ionian b6 and Phrygian b4 also have augmented chords. We can also find °7 chords in Dorian b5, Lydian b3, and Locrian bb7. This make Lydian Augmented #2 a great way to connect modes via inversions of Ab+ and Ab°7. Try playing eight bars consisting of CMaj7 (C-E-G-B) to Em7 (E-G-B-D) to FmMaj7 (F-Ab-C-E) to F°7 (F-Ab-B-D) to Ab+ (Ab-C-E) to G7 (G-B-D-F) to Dm7b5 (D-F-A-C) to C (C-E-G-B-C). It’s a long progression, but it takes us through our augmented and diminished chords as we travel to and from C.

If you’re having trouble using this mode, then you may be tempted to think of it as Aeolian b1. There is no such thing as a b1 as it would cause an impossible overlap with a major 7th degree and a diminished tonic. Instead, listen to how the Aeolian degrees 2-b3-4-5-b6-b7 have been augmented (or raised) to become #2-3-#4-#5-6-7. In the chart below, notice how the degrees all line up. If we try to use Ab Aeolian 1b, then the degrees line up, but the notes do not even though the intervals between notes are correct. We could try to line up all the notes, but then the degrees would all be wrong.

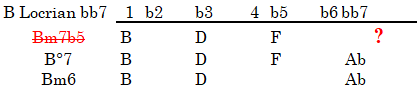

The last mode is another one that makes a lot of sense. Locrian bb7 takes our half-diminished mode of Locrian and cranks up the tension with a fully diminished structure. We get the same usefulness of D°7, F°7, and Ab°7 as inversions along with the tension of Locrian caused by B Locrian bb7’s first degree (the note B) being the leading tone of C.

The thing that makes this mode stand out is the bb7 because it allows for °7 and m6 chords. We used the 6th degree as an equivalent to bb7 in Dorian b5, Lydian b3, and Lydian Augmented #2. In Locrian bb7 we are using the bb7 as an equivalent to the 6th degree. Now we can play Bm6 in a “Locrian style” mode to decrease tension. Playing B°7 (B-D-F-Ab) to Bm6 (B-D-G) to Am (A-C-E) to Ab+ (Ab-C-E) to G7 (G-B-D-F) to C (C-E-G) lets the tension drop a little in the first three chords before using more tension in Ab+ and G7, which then resolves to C. Am is not part of C Harmonic Major, but we can still use it.

Blending Melodic With Harmonic

We’ve covered quite a lot of material, but if you think about it all we did was flatten the Major Scale’s sixth degree. This one change created a variety of sonic textures for us. Your “homework” for this lesson is to play the Major Scale and add in a minor sixth.

We can use all the standard modes of the C Major Scale as our main “pallet”. We can then choose when to flatten the sixth degree. In C Major the sixth is A, so we gain Ab. A simple example would be to play a ii, V, I progression of Dm, G, C. This uses D Dorian, G Mixolydian, and C Ionian. It’s just three chords, but we can alter the note A to become Ab at any time. Now we can play iiø, G, C with the corresponding modes D Dorian b5, G Mixolydian, and C Ionian.

Another example would be to use Ab+ or Ab°7 between G and Am. Playing G, Ab+, Am is a “walk-up” because we walk the root note up through G, Ab, and A. We can also do a “walk-down” by playing Am, Ab+, G to take the root note downward. Remember that augmented chords are made of only root notes, so we can also use C+ and E+ between G and Am as well.

Notice how the notes C and E move down to B and D, but are delayed in that descending movement by the Ab+ chord. We could opt to play Am, Ab+, Gsus4, G and delay the note C longer when playing Gsus4 (G-C-D).

If we play either G7, Ab°7, Am or Am, Ab°7, G7, then we have two more phrases that walk the root. This time we have Ab°7, which is an inversion of B°7, D°7, and F°7. While augmented chords help to create movement, diminished chords help to create tension. This time the Ab chord causes tension that is resolved into Am, which is A Aeolian’s i chord.

Making use of inversions of Ab°7 allows the tension to remain, but the context changes due to the lowest tone of the diminished chord. Try out both movements shown above and listen to how Ab°7 and F°7 have tension that leads to Am, but have different context between the chords G and Am.

A final example of using Harmonic Major with Melodic Major is in any tried and true chord progression. The vi, IV, V, I is used in many popular songs. In C Major the chords are Am, F, G, C. We can add in Ab+ or Ab°7 and alter chords like F, G, and C to be FmMaj7, G7 b9, and C+. We can also add to the progression by using the other chords of C Major like Dm, Em, Bm7b5 and their Harmonic Major counterparts.

The only thing to remember is that Ab replaces A when going from C Melodic Major to C Harmonic Major and that this alteration lasts as long or as little as you like.

Use the chart below for any chord progression in the key of C. Play anything you like in C Major and then alter one part to see where it takes you. These sounds will be very different, but that is what we want as we begin to expand our pallet of sounds. Now go have some fun!