Why Should We Analyze Music At All?

When listening to music on the radio, a streaming service, or any other variety of media you’ve probably come across a song that sounds familiar. You might hear part of a song and think, “Hey, I know this one,” only to find out that it just sounds familiar. Well, there’s a reason for that. Musicians tend to use “progressions” as the backbone of musical structures.

A progression is simply an order of chords that typically repeats. One of the more popular progressions is the 6-4-5-1, written as vi-IV-V-I. If we think of the sequence of notes in the Major Scale as “do-re-me-fa-so-la-ti-do”, then a 6-4-5-1 would be sung as “la-fa-so-do”. Examples of this progression include “Duke of Earl” by Gene Chandler, “Purple Rain” by Prince, “Crocodile Rock” by Elton John, “The Reason” by Hoobastank, and a slew of song by the Beatles such as “All My Loving”, “A Hard Day’s Night”, and “Please Mister Postman”.

This progression is so popular that it’s almost hard to not find it. Check out “Last Kiss” by Pearl Jam, originally written by Wayne Cochran in 1962, and listen for the chords in “Oh, [I] where oh where can my [vi] baby be? [IV] The Lord took her a- [V] -way from me. [I] She’s gone to heaven, so I’ve [vi] got to be good so [IV] I can see my baby when I [V] leave this [I] world.”

By understanding progressions, we can get a feel for what to expect in a song. This may seem like we are just boiling down all our favorite songs into overly simplified sets, but it allows us to gain knowledge on the musical structures used so that we can do more with them. Let’s stick with “Last Kiss” and see what else we can do with it after we go over some of the basics of analysis.

The Basics of Roman Numeral Analysis

In previous lessons and articles, I’ve used Roman Numeral Analysis, which is a way to describe chordal structures rooted in degrees of a scale or mode. The degree used can be any of the degrees of the Chromatic Scale: 1, b2, 2, b3, 3, 4, #4/b5, 5, b6, 6, b7, and 7. To make this easier to understand, let’s start with the four basic triads (three note chords): Major, Minor, Augmented, and Diminished.

Major triads use degrees 1-3-5. A Major chord is written as an uppercase roman numeral, so a Major triad can be notated as I, bII, II, bIII, III, IV, #IV, bV, V, bVI, VI, bVII, or VII. Each triad number references the root note, so starting with C as 1 we have the chromatic chords of C, Db, D, Eb, E, F, F#/Gb, G, Ab, A, Bb, and B.

We can do the same thing with Minor triads use degrees 1-b3-5. With C as the first degree note we can use Cm, Dbm, Dm, Ebm, Em, Fm, F#m, Gbm, Gm, Abm, Am, Bbm, and Bm. These chords can be notated with lowercase numbers as i, bii, ii, biii, iii, iv, #iv, bv, v, bvi, vi, bvii, and vii.

Augmented triads are simply Major chords with a sharpened fifth degree, so their formula uses degree 1-3-#5. These triads are notated by using uppercase numbers with a “+” symbol to show that the fifth degree is augmented or “raised”. Starting with C as the first degree we get the chords C+, Db+, D+, Eb+, E+, F+, F#+/Gb+, G+, Ab+, A+, Bb+, and B+. Roman numerals for these chords are therefore I+, bII+, II+, bIII+, III+, IV+, #IV+, bV+, V+, bVI+, VI+, bVII+, and VII+.

Diminished triads are Minor triads with a flattened fifth degree and use the formula 1-b3-b5. Sticking with the same notes we get the chords C°, Db°, D°, Eb°, E°, F°, F#°, Gb°, G°, Ab°, A°, Bb°, and B°. We continue to add the “°” symbol to our lowercase numbers to get i°, bii°, ii°, biii°, iii°, iv°, #iv°, bv°, v°, bvi°, vi°, bvii°, and vii°.

It is important to note that the formula for each chord DOES NOT come from the scale used. For example, our C Chromatic Scale that we’ve been using has the notes C, Db, D, Eb, E, F, F#/Gb, G, Ab, A, Bb, and B. If we play a C Major triad, then we use the notes C-E-G because C is the first degree, E is the major third, and G is the perfect fifth (1-3-5). If we play an Eb Major Triad from this same scale, then we use the notes Eb as the first degree, G as the major third, and Bb as the perfect fifth. This keeps the formula of 1-3-5 the same in both triads, but they are notated in analysis as C is I and Eb is bIII. Check out the diagram below for the standard chords of the C Major Scale with some borrowed chords to fill in the gaps so that we can utilize a C Major-Chromatic Scale.

Without getting ahead of ourselves and diving into all of those borrowed chords we can still get a lot out of this chart.

Every degree can be the starting point of a chord and mode.

Each roman numeral number represents the degree that the root note starts on.

Each Maj7 chord uses the formula 1-3-5-7, is an uppercase number with “Maj7” added, and is associated with Ionian or Lydian.

Each m7 chord uses the formula 1-b3-5-b7, is a lowercase number with “7” added, and is associated with Dorian, Aeolian, or Phrygian.

The Dominant 7 chords use the formula 1-3-5-b7, are uppercase numbers with “7” added, and are associated with Mixolydian.

The Half-Diminished chords use the formula 1-b3-b5-b7, are lowercase numbers with “ø” added, and is associated with Locrian. The “°” accounts for the 1-b3-b5, while the slash in “ø” notates the b7.

There are no augmented chords because everything used in this chart comes from the Major Scale, which does not allow us to naturally build augmented chords. This does not mean that we are forbidden from using that chord. Playing a progression like Am, Ab+, G, C is a cool way to “walk-down” from Am to G. This progression would be notated as vi, bVI+, V, I. If we “walk-up” using G, G#+, Am, G7, C we use the roman numerals V, #V+, vi, V7, I to describe that as ascending rather than descending.

A ton of information can be derived from roman numeral analysis, so let’s put it to the test with “Last Kiss”.

Exploiting the 6-4-5-1

“Last Kiss” is in the Key of G, so the chords used are I is G, vi is Em, IV is C, and V is D. We can play the song starting and ending on 1 with a 6-4-5-1 progression as G followed by Em, C, D, and G repeated. We can just play these four chords continuously and the song sounds fine, but what can we do with it?

Well, we can start with the modes associated with each chord by looking at the chords C, D, and Em. Each root note is a whole step apart and there are two major chords below a minor chord. Matching it to the chart below we can quickly find that chords 4, 5, and 6 are all a whole step apart and are two major chords below a minor chord.

Since D is our “five chord” or V chord, we can go down a fifth to G. That is our first degree. By practicing writing out the Circle of Fifths we know that the notes in the Key of G are G, A, B, C, D, E, and F#.

Using the chart above we can work out what modes match with our chords. Ionian matches with I, Lydian with IV, Mixolydian with V, and Aeolian with vi. By practicing our modes, we can adjust our chords to sound more modal than just as triads.

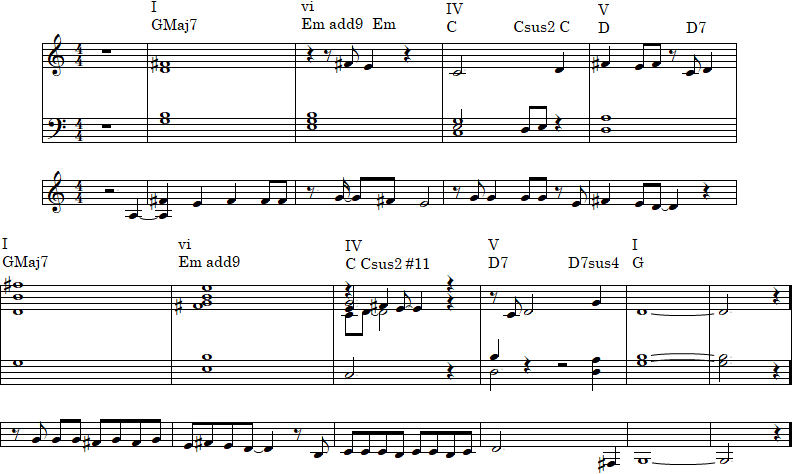

The first chord can be played as GMaj7 (G-B-D-F#) to easily fit the degrees of the Ionian mode.

The Em chord could be played as Em7, but that’s kind of boring. Aeolian has a major second, so let’s put that in the second octave of the chord to make an Em add9 (E-G-B-F#).

C lines up with Lydian and while a CMaj7 #11 sounds cool, we’ve already used F# in the first two chords and we’ll use it again in our D chord as the major third of D. I’ll play Csus2 (C-D-G) so that we still use something more interesting than just a C triad.

The D note in the Csus2 will also help us lead into a D chord like D7. This chord is the Dominant Fifth of GMaj7 and has a relationship of V7/I (V7 to I).

Now we have some chords that are more than just triads which will help us to drive the melody. The note F# will be a focal point of each chord because it is the Leading Tone in the Key of G. This means that F# naturally leads up to G. By playing chords that move that note up to G or down to E we can push and pull the melody’s tension as we move the melody in relation to G.

Another thing we can do is exploit the note C. This is the b7 of D, so playing it in relation to D will give us the sense of a D7 chord. This is similar to playing a D7 arpeggio where we play the notes of the chord separately, but by focusing on the notes C and D in a melody that replaces D7 we can still arrive at GMaj7 with the same pull. Check out the audio clip below along with the notes used. Watch for the note F# to be the focus of the melody’s tension for chords I and vi. Notes C and D generate the movement of a D7 chord leading back to G for the IV and V chords.

Modifying Progressions

There are so many progressions that work great for multiple reasons. Look at some of the songs you’ve learned and try playing them modally as we’ve done with “Last Kiss”. Another thing we can do is to modify the progression. Simple changes like turning a ii, V, IV, I into a ii V, iv, I can make dramatic changes.

Aside from learning more songs and analyzing them, I want you to try your hand at the Twelve Bar Blues as this lesson’s exercise. The progression is literally twelve bars that uses just three chords: I, IV, and V. This is typically played in the keys of G, C, F, and Bb due to being great for instruments that are used in blues and jazz like guitars and saxophones, but it can be played in any key. There are several versions of this progression, so I’ll use the format below so that we have specific chords to use.

I’ll stick with the key of C, so our chords are C, F, and G. Using G7 in the last bar makes a lot of sense because of the V7/I relationship. Since this is the blues, we can play many of these chords as Dominant 7 chords and use Mixolydian or the Major Blues Scale (degrees 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6) over any of these chords. This updates the progression to…

We can play C Ionian (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) over the I chord, F Major Blues (F, G, A, C, D) over the IV chord, and G Major Blues (G, A, B, D, E) or G Mixolydian (G, A, B, C, D, E, F) over the V chord. Playing B as the Leading Tone of C in the last bar, F as the b7 of G, or both B and F as a TriTone interval helps the whole progression wrap back into itself with C at the first bar.

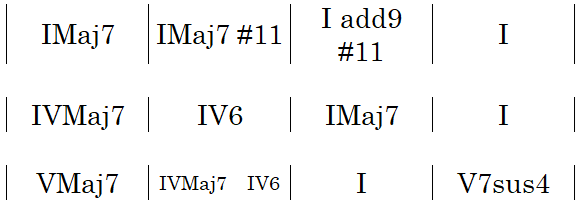

We can also “jazz it up” by playing some modal chords. We can replace C Ionian with C Lydian just for the sake of borrowing a mode that also uses a Maj7 chord, so that we can play the I chord as C Ionian or C Lydian to gain CMaj7 #11 and C add9 #11. F is our diatonic Lydian chord so FMaj7, FMaj7 #11, and F6 are all cool jazzy chords that fit the Lydian mode. G Mixolydian has G7 so let’s add Gsus4 and G7sus4 for some brightness. Since we used C Lydian we are borrowing the note F#. Adding that to a G Major chord makes it a GMaj7 that also has some brightness. This makes the progression jazzier with…

A final thing that we can do is make all the chords minor. To do this we go from C Ionian to the parallel mode of C Aeolian. Now the chords are i as C Aeolian, iv as F Dorian, and v as G Phrygian. Doing so creates a very interesting and laid back feeling, but we want to make sure that we still have a V7 in the last bar. To do this we’ll borrow Phrygian Major, which is Phrygian (1 b2 b3 4 5 b6 b7) with a major third degree (1 b2 3 4 5 b6 b7). Now we can play a Dominant 7 chord of G7 (G-B-D-F) within G Phrygian Major (G, Ab, B, C, D, Eb, F). This mode comes from the Harmonic Minor Scale. We will be getting into that scale and its seven modes soon enough, so let’s focus on testing the waters with this one change to get…

Your task for this lesson is to take the Twelve Bar Blues, or any progression, and mix it up with roman numeral analysis. Try minors in place of majors and majors in place of minors. Add in V7 to I and V7 to i at the end of phrases. Write out what modes you are using along with their scales and notes. Try out suspended chords like sus2 and sus4. Add in upper extensions like add9 and #11. Do what feels right, funky, and interesting to you.

Below is an example of a heavily modified Minor Twelve Bar Blues in A Natural Minor, aka A Aeolian, and make it a Sixteen Bar Blues. I’ll include Dorian b5 from the Harmonic Major Scale to spice it up a bit since it uses Ab which is enharmonically equivalent to the G# in Phrygian Major from the Harmonic Minor Scale. I’ll even set a nice spot to play A Harmonic Minor. Try it out with any tempo and rhythm. Ask any questions you have in the comments. Until next time!