Using Musical Note Naming to Your Advantage

How to use patterns in note names to recognize and access structure.

Are There Too Many Notes?

When a student is first learning about music, they tend to learn the C Major Scale first because it uses no sharp of flat symbols. With the letters C, D, E, F, G, A, and B, the student is expected to learn this order and embrace it. What I’ve noticed is that this is a good starting point, but rarely do students learn about other keys or scales for quite a long time. This can cause new musicians to become exceptional with the C Major Scale but have a hard time transitioning away from it.

Another problem that can arise is that the student is not introduced to the Circle of Fifths, Order of Sharps, Order of Flats, or even Key Signatures. While these things can help in understanding many aspects of music, I’ll use them sparingly and try to stick to concepts so that we can all see why sharps and flats are so important. The biggest concept that you’ll see is that there are not a lot of options for how notes are named because of the first rule of note naming.

Rule #1: Each Letter Is Used Only Once

Starting with the C Major Scale with the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. It is not C followed by Cx (aka C Double Sharp). It is also not C, D, E, E♯, G, A, C♭. Using each letter in alphabetical order and only once helps to lock down note names in the same order every time. This is the most important rule in note naming, so keep it in mind as we continue.

Gaps in the Major Scale

The Major Scale is a series of seven notes with seven letters. Each note is spaced out per the design of the scale using half-steps (the distance from one tone to the next semi-tone, like C to C#) and whole steps (the distance from one tone to the next tone, like C to D).

Above is the C Major Scale with each degree number over each letter used. Notice the five gaps in the scale. This format is like a piano with the letters being the white keys and the gaps accounted for with the black keys. To start understanding how the gaps are filled in, we should look at the C Natural Minor Scale with the notes C, D, E♭, F, G, A♭, and B♭. Below we have flattened three notes to create this scale: E, A, and B. Notice that our first rule is used in the order of letters. Also, the flattening of E, A, and B has not replaced these letters. Instead, they have been literally diminished into a flat form of the note. In this way, E and E♭ are both “E notes”. One is natural and one is flat (aka diminished).

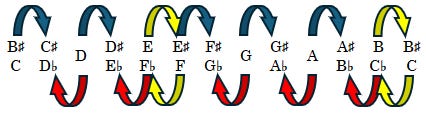

We can also sharpen (or augment) notes to fill in the gaps. Below are all the standard note names in all fifteen specific keys. Using all the sharp notes or all the flat notes would create a scale with two natural notes and five “accidentals”, which are the non-natural notes.

Some keys do have six or even seven accidentals. Keys like F# Major use the notes F♯, G♯, A♯, B, C♯, D♯, and E♯ and may look bizarre due to the E♯ note. The note E♯ cannot be F because that letter has already been used by F♯.

The Major keys that go beyond five accidentals are C♯, F♯, G♭, and C♭. Rather than think of keys as going from simple with no accidentals to complex with too many accidentals, we should think of keys and the note names system as a device that makes using multiple scales easier.

Key Changes

Modulating between C Major and C Natural Minor is one of the most useful ways to add extra color to a scale. Without having to completely understand the Circle of Fifths, we can simply think of a clock and the twelve positions. On the Circle of Fifths, C Major is at the top (12 O’clock) and C Minor is nested with E♭ Major on the left side of the circle (9 O’clock). With twelve positions to use it can be daunting to have to think of every note to keep track of what notes we are using. Thankfully the note naming convention helps us.

Above we have C Major and C Natural Minor. The letters that gain accidentals are the third, sixth, and seventh degrees. Just like with letters being used once, numbered degrees are used only once. This allows musicians to use the Major Scale and then simply think of three positions that need to be flattened. I don’t have to know the letter name. Instead, I can focus on degrees three, six, and seven and know that the natural positions give me the Major Scale, while the flattened positions give me the Natural Minor Scale. When I go to write down what I played, I can then watch for these three positions to change and know what letters to flatten or return to a natural state.

Since C Natural Minor uses the same notes as E♭ Major, we can use the same concept to make it easier to use a key with three flats and a key with six flats. Below we have E♭ Major and E♭ Natural Minor. The notes E♭, A♭, and B♭ and not the third, sixth, and seventh degrees. Those degrees use the letters G, C, and D, and we can focus on them as the third, sixth, and seventh degrees to adjust. There is no need to constantly account for all seven notes. Only the few notes that are being diminished or augmented need to be watched, and only when they are used.

The Secret Order

Now that we’ve gone through the concept, let’s make this even easier. Below are the Orders of Sharps and Flats. Notice how they are opposites of each other: F-C-G-D-A-E-B in reverse is B-E-A-D-G-C-F.

Below is a very big chart. Starting with C Major we have no accidentals. Moving up the chart to G Major we have one accidental, which is F♯ because it is the first letter in the Order of Sharps. The next key up is D Major with two accidentals: F♯ and C#. These are the first two letters in the Order of sharps.

We can also skip around. In B Major we have five accidentals. The first five notes in the Order of Sharps are F, C, G, D, and A, so they are all augmented or sharpened. The same method can be used to find which notes are natural. In A♭ Major we have four accidentals and with the first four letters in the Order of Flats being B, E, A, and D, we know that those four letters become B♭, E♭, A♭, and D♭. With four letters altered, we also know that three letters are unaltered. The last three letters in the Order of Flats are G, C, and F, so they remain natural in A♭ Major.

Another great use of these orders is when we get to key signatures. Below we have two keys with three accidentals each. One key uses sharps and the other uses flats. Notice that the letters that are altered (sharpened or flattened) are the first three letters from their repective order. Also notice how the signature has them listed in the same order.

In the chart with all fifteen keys, there are horizontal lines next to B Major and D♭ Major. These lines separate the top three and bottom three keys of the chart because they are enharmonically equivalent to each other. Below we have these keys in direct comparison with each other. While the note names are different, the spacing and positions line up. While C♯ and D♭ are distinct and unequal notes, the overlap they share makes them equal in position only. There are specific differences between these notes when wavelengths are calculated, but for the purpose of functionality we can say they are the same note.

Practice, Practice, Practice

When using the Order of Sharps, the Order of Flats, and concepts like altering degrees, it’s important to learn these things in bite sized pieces. Don’t try to learn all of this at once. Instead, start with a familiar scale and then move up or down the above chart and look at what happened to the letters and degrees. Going to and from C Major, F Major, and G Major can be a great starting point to help you get used to note naming, degree assignment, and even where to put your hands on an instrument.