What the Heck is the Third?

In the world of music "the third" is the third degree of a scale. Typically, this degree helps to create major or minor chords, but we can use it when constructing augmented and diminished chords. Today we'll stick to only major and minor chords.

So, what is the big deal with doubling or using two third degree notes? Well, our ears are so fine-tuned to the world around us that playing a note and either type of third degree note gives us a specific sound. Think of someone saying, "Oh, hi." "Oh" is the first note and "hi" will use the third degree to communicate emotion. That emotion can be joyous with the major third or melancholy with the minor third. Try saying, "Oh, yeah" in both ways and listen to the notes you make. There's a good chance that "Oh" used the same note, but "hi" changed just a little. That little change is the power of the third degree because a slight change in pitch completely changed the context of, "oh, hi."

To Double or Not to Double, that is the Question

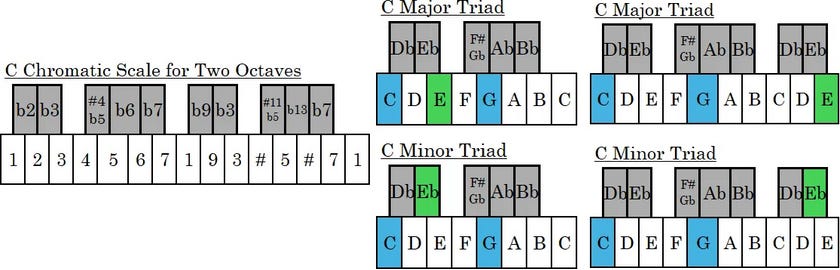

When we play major and minor three-note chords, called triads, we typically use two formats. The major triad uses degrees 1-3-5 and the minor triad uses degrees 1-b3-5. Below the C major and C minor triads are shown against the piano. As long as the root note is C, the below chords are still major and minor chords.

But what happens if we double the third and play that note in both positions? Since our ears can hear subtle changes in pitch, we hear both third degree notes, yet we have a hard time understanding where the quality of the third is coming from.

Remember how we described the major and minor thirds as joyous or melancholy? Imagine doubling up on either emotion. It doesn't make a lot of sense. Are we joyous and boastful from a low tone or joyous and light from a higher tone? Take a listen to the audio clip below and listen for the doubling of a third to actually weaken the emotion it conveys. If you are using headphones or speakers the thirds will be played to the right side. Headphone will likely be your best tool to hear the “warbling” that two thirds creates.

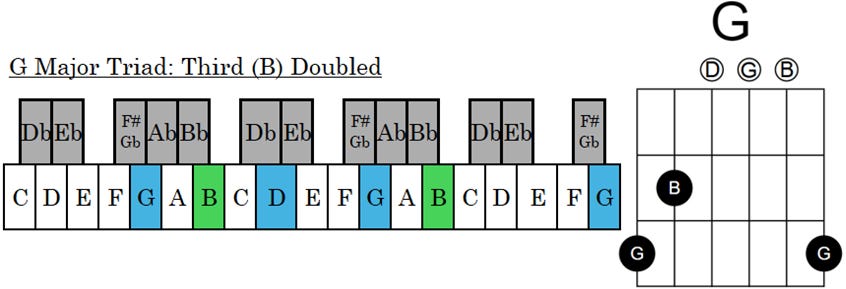

Because doubling the third weakens the effect of both third degree note, we rarely double that note. The doubling effect is avoided so much that many chord shapes/grips only use the third once. Check out the diagrams below for the C and G chords on the guitar along with the way they would be voiced on a piano. The third is only used once in example.

When Should We Double the Third?

Since doubling the third has a specific effect we can use it to our advantage. Two common C and G chords on the guitar use doubled thirds. Check out their shapes for guitar and piano.

These two guitar chords have weakened thirds that cause them to be felt as laid back and easy going. These are perfect for strumming by a campfire. You can therefore think of doubling thirds as "the campfire effect". We are now laid back and relaxed. We can be joyous or melancholy, but the feeling of relaxation clouds those emotions. Take a listen to the C and G major triads played with one third. Then listen to the same chords with doubled thirds for a mix of vague emotions.

Applying Thirds to Melodies

An arpeggio is a "broken chord", which means that the notes of a chord are played one at a time. Playing doubled thirds in an arpeggio still creates the doubling effect, so what about melodies?

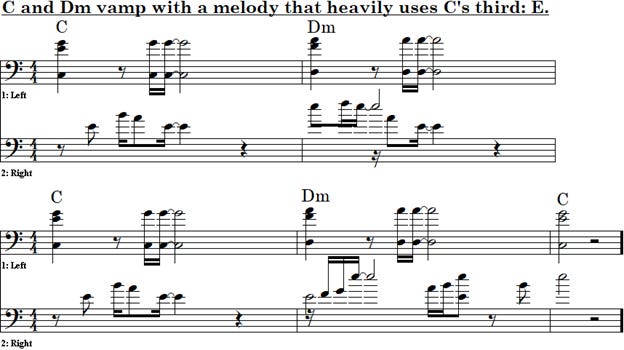

It depends because melodies can go over multiple chords. This allows the third in the first chord to become another degree in the next chord. By playing melodies across two different chords, we can easily avoid doubling the third.

Vamps have other consequences. A vamp is a movement back and forth between two chords. If our melody starts with third of a chord, then it becomes another degree in the second chord. When we come back to the first chord, we now have the opportunity to play the first chord's third in another pitch and double it. But that does not double the third.

By playing that second chord we change the context of our notes. Check out the example below. The first set plays C, Dm, C with a melody that uses the note E as the third. By playing Dm we change the context, it becomes the 2nd degree note relative to D. When we return to C we essentially start over and reset and let the note E reset as well. The second example we have the same melody, but the Dm chord is committed. Without Dm we have C as a continuous root note. This makes E act as third throughout the melody. The doubling effect exists, but it is subtle as it makes the melody relax when the note E is used a second time.

Let me know how doubled thirds impacts your playing or compositions in the comments below. I’m sure others out there would love to hear what you’ve come up with as well. Until next week!