The One Octave Challenge

Applying a minimalist view to gain a larger perspective of musical control.

The Idea

There are many exercises that musicians can use to sharpen their skills. I came across a way to think about playing music in simpler terms because I wanted to eliminate the daunting task of playing with all notes available. For example, on a piano there are eighty-eight keys and each key is a specific tone. Out of that set of optional notes, there are twelve note names (with a little overlap). Rather than trying to improvise a song out of eighty-eight options, I decided to limit myself to twelve neighboring notes. This way I still had every note needed to play a song, but I would be limited to a specific set of twelve notes. This was a bit of a challenge at first since using only these few notes spanned a musical distance called an octave. And that is where the “One Octave Challenge” began.

Jumping Into the Challenge

Before we get started, please note that I will use the piano and guitar as examples, but this exercise can be applied to any instrument.

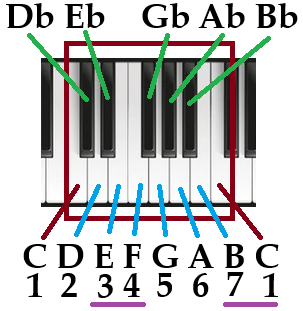

The piano chart shown above focuses on one octave from the note C to the next C. We will be focusing on the major scale for now, which uses the degrees one through 7 and are listed with the corresponding notes. The flat notes are also listed, but without their degrees. This is just for reference. Focus on the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and C.

For a quick recap on the major scale, degrees 3 & 4 and 7 & 1 are a half-step apart, meaning that those degrees are right next to each other. The other degrees are separated by a whole step, meaning there is a note between them.

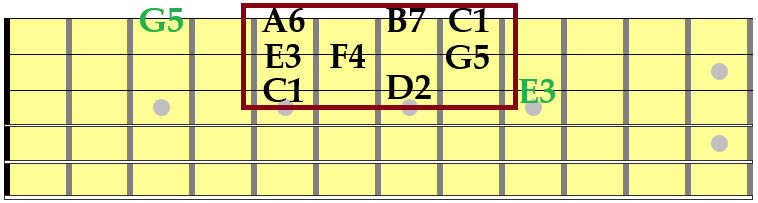

The guitar chart shows the same C major scale notes and their degrees. I’ve omitted the flat notes for clarity so that the guitar chart is not cluttered. In this chart, please note the green notes of E3 and G5. Those notes are the same pitch as the black E3 and G5, so they are allowed in the challenge.

When reviewing these charts you should focus on the idea of using only pitches from C to C. This does allow for the starting note to be used twice, but that is part of the challenge.

Now lets get into some chords!

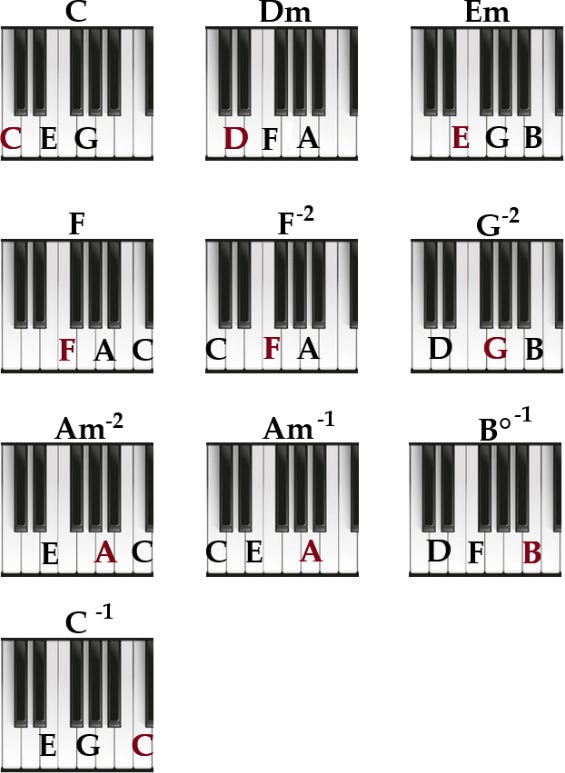

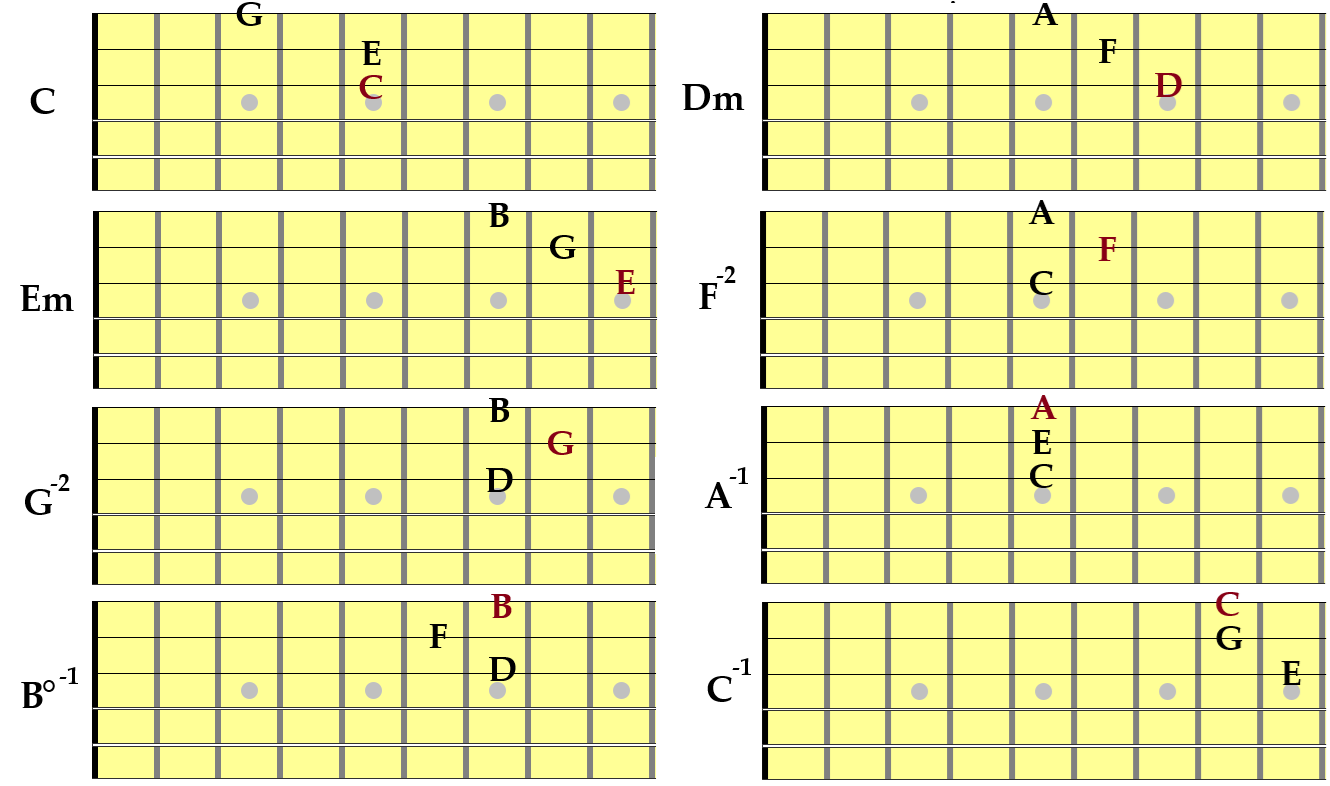

Below are the three-note chords that we can access within this one octave. They are C major, D minor, E minor, F major, G major, A minor, and B diminished. Every major scale has these seven chords in this order: Major, Minor, Minor, Major, Major, Minor, Diminished.

Each chord has the root note listed in red so that it stands out. When these chords are constructed, we start with the root note and then skip notes to reach the next one in the chord. So C major is C (skip D) E (skip F) G. This is easy to see for C, Dm, and Em. When we get to the F chord, there are two options: F-A-C and C-F-A.

The F-A-C chord is in “root position” because the root is the lowest tone. If we put any other note in the chord in a lower tone, then the chord is “inverted”. Using the next note in from the root is a “first inversion” and using the next note in is in “second inversion”. Since C is the third note of F-A-C, the chord C-F-A is an F major chord, but it is in second inversion. These are notated by the -1 and -2 symbols. By limiting ourselves to one octave we two C majors, two F majors, and two A minors. However, chords like the two A minors must be inverted due to the one octave limitation.

The guitar charts are similar in that there are some mandatory inversions. With the guitar, knowing where the root note is by string position can be very useful. The strings on these charts are the six horizontal lines. The top line is the first string and the bottom line is the sixth string. Being able to target notes for melodies (which is to play a melodic set of notes that leads to a targeted note) is great, but being able to target chord tones is even better. Imagine playing a melody that you want to lead to an Am chord. In this one octave, there are three notes that can be used. Each note provides part of the structure of an Am chord. If you’re not familiar with chord/note functions, then check out my Archives section and search for “Function Harmony”. There’s a lot of articles that use functional harmony.

For My Single Note Friends

For the single note players that use the saxophone, flute, harmonic and similar instruments… do not think I forgot about you. You can play chords as arpeggios, which means to play the notes one at a time. I suggest playing a melodic line at a slow to moderate tempo. When you want to play a chord, play the three notes of the chord as a triplet. That way the melody is heard as is and the arpeggiated chord is pressed together using time itself. Play around with this idea and you’ll begin to use chord tones in a more meaningful way.

How to Use The Challenge

Now its time to play a song. Pick anything that you can play in C Major. Keep in mind that this works everywhere, so if you want to apply it to E Major then just use one octave from E to E. You can do this in Minor keys and modes as well. As you play your song, stick to the notes that are available.

The point of this is to begin to recognize inversions that you like. This will expand your personal list of favorite chords and melodic lines.

Even melodies can be “inverted” by forcing the notes to be ones that are found in one octave. The only time you get two pitches for one note is the beginning and ending note. This lets you decide where the song should move ascending or descending to that note. It also forces you to make a decision, but just once. For example, a chord progression like Am, Dm, G, C can have a few ways to be played depending on the instrument. Try playing these chords with short melodic lines between each one. Remember, this challenge is not to test what you can do. Its to test what you can discover.

When you are ready to move out of C Major in one octave, try out C Major from D to D. C is still the tonic note and your chords are the same, but now you have to rethink what you already learned. You can do this with any scale or mode. Just stick to one octave and embrace the inversions.

The Two Octave Challenge

There’s only one thing left to do: add another octave.

The reason for this is because in any octave higher than the first one used, the degrees 2, 4, and 6 become 9, 11, and 13. If you see a chord using a #11, then the scale or mode it is connected to has a #4 in it because a #4 in a higher octave becomes a #11.

So lets imagine that you want to use a Csus2 chord. That would be the notes C-D-G. In the chart above there are many ways to construct this chord out of degrees 1, 2 or 9, and 5. But what about a chord like C add9? That chord is C-E-G with an added D in a higher octave. That is what makes the D note a 9. If you had all four notes in the first octave, you would play C-D-E-G or D-E-G-C and that “crunched space” between D and E would not sound that great. Placing the D note in the next octave gives it some breathing room.

There are two ways to use the Two Octave Challenge. One is to place chords and root notes in the first octave with melodies in the second octave. If you play a first octave chord like C6, which is C-E-A, then you are using an Am in first inversion. The melody that you play in the second octave should reflect your intent. Is this a type of C chord that the melody works with, or is it an Am chord in disguise? Now is your chance to experiment with melodic lines that interpret the harmony of the chord the way you want it to.

The other way to use this is to start blurring the two octaves. A chord like CMaj7 uses the notes C-E-G-B. Try placing the notes C and G in the first octave with E and B in the second octave. Now create a melodic line that uses these four positions of C-G-E-B as way-points for your melodic movement.

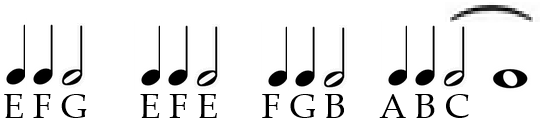

Here’s an example of what you could play.

Notice how there are no ledger lines. That is so you can decide which specific tone to use. The idea of these short melodic lines is that each one ends on a note in the CMaj7 chord. Try this in both one and two octave formats and see where that takes you.

I’m sure there are plenty of other ways to use a limit like an octave to find new way to control music. Explore your own ideas as well and never be afraid to ask, “What if I…?” That question has led me to many discoveries.