Pivot Scales

Taking the concept of pivot chords to the next level.

PIVOT! PIV-OT!

Many of our favorite songs start with a musical key, which can typically thought of as “Do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do.” There are twelve notes that could be “do”. After that the rest of the six notes of “re” through “ti” can be thought of as higher pitches. That’s the simple way of thinking about what a musical key is.

Lots of great songs create movement, mood, and storytelling by using just seven notes. But when an artist can’t find the sound, they want within seven notes it becomes obvious that we need more notes. So, what notes should be added? It depends on how much change the storytelling requires. We could alter six of our seven notes or even add in all the missing notes for extreme changes. Today we’ll stick to small changes that make a huge difference.

Think of this lesson as a guide to changing “tone” rather than “color”. If we think of our seven notes from “do” to “ti” as colors, then the changes we will make darken or brighten those colors. Rather than changing keys or scales to something with drastically different colors, we can allow simple changes to our current key to act as tone shading. In this way we can tell a story, shade part of it, and still stay within the main thought of our story.

Why Should We Pivot?

Many musical keys share similar notes with other keys. This allows “neighboring keys”, which have six out of seven notes matching with a key, to share some of the same chords. In the keys C Major and G Major we have the chords C, Dm, Em, G, and Am in both keys. F, Fm7b5, Bm, and Bm7b5 are the other chords that can be in C Major or G Major, but not both. Now think of a song that could use C, Dm, Em, G, or Am. Those chords allow us to “pivot” between C Major and G Major because they are in both keys. We can play a song in C Major with Am, Dm, G, C and then later use Am to Pivot into G Major with Am, D, C, G. The chord D is in the key of G, but not C. Pivoting on Am got us to the key of G and allowed us to access D as a new chord. To get back to the key of C we can then pivot on Am and play Am, Dm, G, C again. Check out the diagram below for a visual on how pivoting on a chord works.

Pivoting Scales

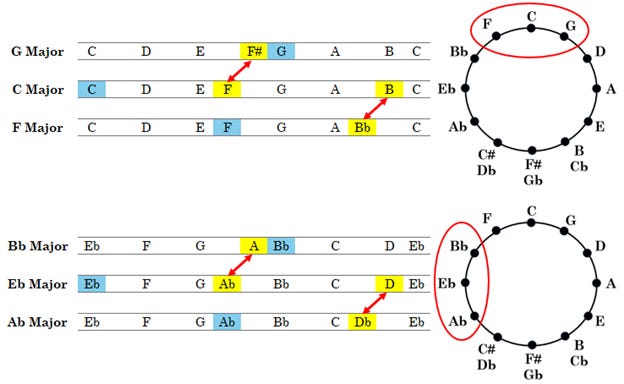

We can actually get a little advanced by making the concept of pivoting simpler. Below we have the keys of G, C, and F followed by the keys of Bb, Eb, and Ab. What we should focus on first is the key of C.

Notice how out of the seven notes in the key of C Major that we can sharpen the fourth note of F and the set of notes is what we find in key of G Major. On the Circle of Fifths, shown next to each set of keys, we can see that C Major is neighboring both G Major and F Major. To go from C Major to F Major we flatten the seventh note of B to get Bb and access the notes found in F Major.

The point is that we can go clockwise on the circle by sharpening the fourth note or counterclockwise by flattening the seventh note.

Now look at the section using the keys of Bb Major, Eb Major, and Ab Major. If we are using Eb Major, then we can sharpen the fourth note of Ab to get A and therefore access the key of Bb Major. Flattening the seventh note in the key of Eb turns D into Db and gives access to Ab Major. The act of sharpening the fourth note or flattening the seventh note helps us traverse the circle one neighboring key at a time.

This means that we can (1) start in Ab Major, (2) sharpen the fourth note and move into Eb Major, then (3) sharpen the fourth note in Eb Major to get to Bb Major. We can also go in reverse. Starting with G Major we can flatten the seventh note to get to C Major, then C Major’s seventh note is flattened to get to F Major. Three more rounds of flattening the seventh note takes us from F Major to Ab Major. With twelve notes we can imagine sharpening or flattening notes twelve times to go completely around the Circle of Fifths.

Again, it may seem like we are changing keys, but the goal is to change the tone of our colorful notes. The way we do that is through modes.

Modal Pivots

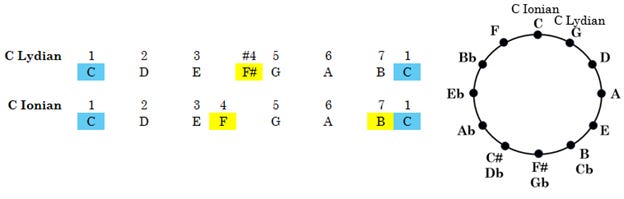

Without diving too deep into modal interchange, modal mixture, and borrowed chords I’d like to focus on modes themselves. Below is C Ionian and C Lydian from the keys of C Major and G Major. As we’ve done before, sharpening the fourth note takes us clockwise on the circle. This time we are not treating G as the tonic. C is and shall be “THE TONIC”. All other notes exist relative to C.

The next chart above lists the degrees within each mode. Next to that are all the modes starting in C. Now here’s where we can stop memorizing degrees, notes, modes, keys, and all that technical stuff. By relying on the “4th ” and “7th” degree notes of any “key”, we can adjust the mode.

Take a look at any mode. Let’s try C Dorian in Bb Major. If we sharpen the 4th degree from Bb Major, which is Eb, then turn our C Dorian mode into a C Mixolydian mode. It’s just like going from Cm7 to C7. We could also go in the other direction. Flattening the seventh degree of Bb Major, which is A, takes our C Dorian sound and recolors it as a C Aeolian sound. Sure, C Dorian and C Aeolian both give us Cm7. The difference is in the modes. Dorian has a 6th degree while Aeolian has a b6th degree. So, in C Dorian we can play Cm6, but changing A to Ab gives us the ability to access Cm b13 or Cm #5.

You may be wondering, “What are we pivoting on?” With chords we picked one chord to pivot on. With scales we are pivoting on six out of seven notes. The one that gets altered is what changes the “tone” of our sounds. This might be something that you have to experience to appreciate, so here’s how to do that.

Take a scale you love and are comfortable playing. Play something and at some point, sharpen the fourth degree note of your key. For instance, if you are playing in the key of C then F will become F#. Play in the key of C and “at some point” use F# instead of F. This can be as part of a chord or melody. That’s up to you. Once you do play something with F# be sure to go back to using F. That brief moment took whatever chord and mode you were in and “sharpened” it. Essentially, you stepped clockwise on the Circle of Fifths for a moment.

Now do the same but flatten the seventh degree. In C Major, B becomes Bb. A quick chord progression with some melody to it could use C, Am, Dm, G, C. When you get to Am, try incorporating Bb instead of B in a melody. Then when you get to Dm try avoiding B and Bb. By the time you get to the G chord you are using the note B again.

Whether you used fretboard patterns, piano scale patterns, or fingering patterns you can find ways to alter the 4th and 7th degrees of any major key to modify modes, chords, scales, and color. Let me know what you find useful or interesting in the comments section below. Thanks for reading and happy practicing!

You and I think alike! https://www.ethanhein.com/wp/2020/scales-keys-and-modes-on-the-circle-of-fifths/