Making Guitar Chord Charts Easier to Use

How to consolidate tons of charts into a few categories.

Back in My Day…

I had the poster shown below in my bedroom when I was first learning how to play the guitar. I even bought a cheap plastic frame for it. There are plenty of versions of this set of chord charts online today, but back in the 90s the internet was just getting started. Having a huge set of information ready at all times was a big deal for me. With this poster I could work on a song and if I found a chord that I didn’t know, then the poster would help me figure out what to play. At least that’s what I thought.

The truth is that it made learning chords more confusing. I would see the same shape used from one major chord to the next. Moveable shapes were fine because I could use the same finger positions and move that “shape” along the fret board. The first problem was that there are twelve notes in an octave. That means that up to twelve of the charts on the poster could use the same shape. The next issue was that a major and minor shape would be different by just one note. Why?! What is so special about that one note? And then there were chords that used the terms “dim”, “+”, “6” and so on in their names. I was playing rock and roll and I never used these chords. So the poster became wall art.

The Missing “Key”

If there was only a key on the poster that could tell me what the heck each symbol meant. Well that’s the point of this article. I want you to be able to see that (1) all chords can be described by a “formula”, (2) guitar chords can be grouped by root note position, and (3) chords consist of four basic types.

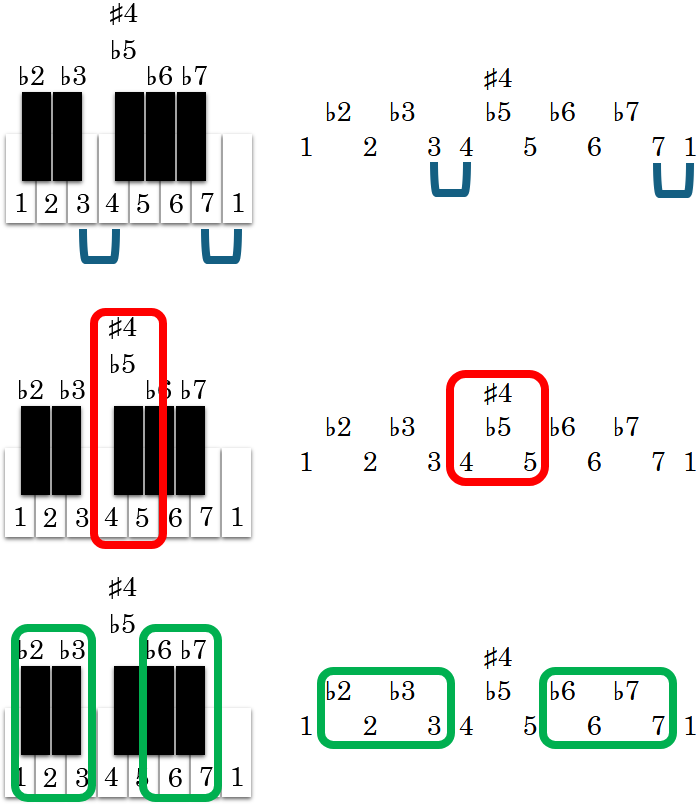

To get started learning guitar chords, we’ll actually use a piano. Below we have the keys associated with the C Major Scale. We don’t need notes right now. Instead we’ll focus on degrees, which are the numbered values in a chord or scale. The first note, or root note, is 1. After that we have numbers 2 through 7 along with some alterations. Let’s make the below charts simple by starting with just the whole numbers 1 through 7.

The whole numbers make up a major scale. In fact, every major scale uses these numbers. The thing to notice is that every number is a whole step apart except for 3 to 4 and 7 to 1. Those two intervals are half-steps, which are pointed out by the blue markers. You can go to literally any instrument and start on any note as 1. Move up a whole step take you to 2. Do that again and you get to 3. Now move just a half-step to get to 4. Keep going and you have a major scale.

In the middle of the scale we have the 4s and 5s. There is a note a half-step between 4 and 5. Scales and chords that use this note use either an augmented 4th or a diminished 5th: ♯4 or ♭5. Think of this as the only “shared” note, which is pointed out by the red markers. 4 and 5 share this position, but only one of them can use it at a time. That’s a nice feature because if you have a 4th degree in a chord or scale, then a ♭5 or 5 is fair to use. The same thing happens when you have a 5th degree, which allows for a 4 or ♯4 to be used.

The remaining notes, pointed out by the green markers, have flattened versions. You can think of these two groups as being between 1 and the middle set of 4s and 5s. In other words, between 1 and 4 you have 2 & 3 along with their flat versions. You can also look between 5 and the next 1, where you’ll find 6 & 7 with their flat versions.

Understanding these degree positions will help you to understand all scales and chords. If this is a bit much for you, then start with the major scale. Then work in the red section, one of the green groups, and then the other green group. You can work these parts in slowly. Take your time, because it really helps with learning music theory.

Major Triads

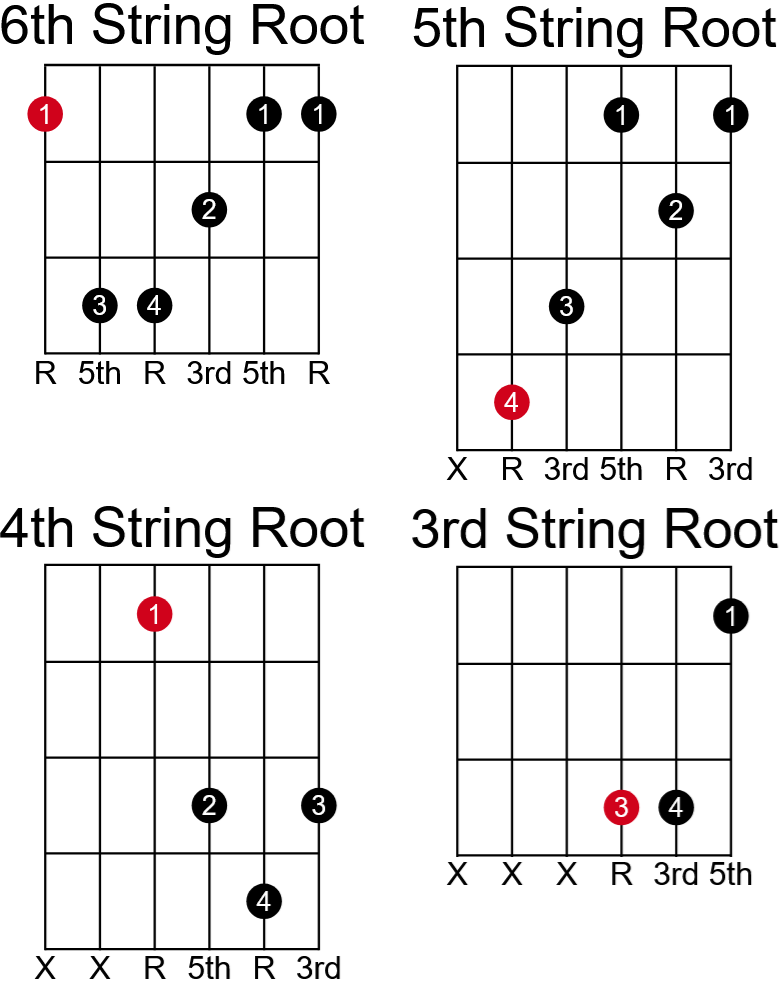

When we are “grouping chord by root positions”, I’ll use just major chords so that you can start to see how this makes playing guitar so much easier in the long run. Keep in mind that I will only show you one chord per root position. There are plenty of ways to make major chords and this is not the only way to do it.

The four charts above are all major chords because they starts with a root note and then use the 3rd and 5th degrees after that. Whether you see a formula of 1-3-5 or R-3-5, they basically mean the same thing. On each of these charts I have the root note shown in red, the fingers used on each position of the chart, and the degrees of those positions at the bottom. Understanding where a root or 1st degree note is in a chord is really helpful when you start to connects chords with scales. It’s also nice to know where your other degrees are and what they are.

Minor, Diminished, and Augmented

Just like learning your whole numbers first and then the alterations of those numbers, we can start with the major chord and alter it’s degrees to get three other common chords.

A minor chord uses the formula 1-♭3-5. You can take any of the above charts and flatten the 3rd degrees to make a minor chord. Some of these chords would be pretty difficult to play, so you would want to use a different “shape” to access degrees 1-♭3-5.

Once you have a minor chord that is comfortable, try flattening the 5th degrees. A diminished chord uses degrees 1-♭3-♭5. You can think of a diminished chord as a “minor with a ♭5”. Rather than make diminished chords another set of oddballs on a poster, we can just think of them as a set that is similar to minor chords. Here’s the big difference: diminished chords are not minor chords. They function very differently due to that ♭5. I know it’s only one little change, but do not try to use diminished chords as minor chords because minor chords create melodies & harmonies, while diminished chords pull us toward melodies & harmonies. That’s the short version of why they function differently.

An augmented chord take a major chord and sharpens the 5th degree. Any ♯5 you use would overlap with the ♭6 in the same way ♯4 and ♭5 overlap. If you use an augmented chord, the formula is 1-3-♯5 and it functions similarly to diminished chords in that it “leads you somewhere else”. We could spend a whole lesson on just augmented chords, so I’ll keep their function simple by saying, “diminished chords lead you away from themselves and augmented chords lead you to something that connects to it”. I know that’s super cryptic, so here’s a brief example. B Diminished (B-F-D) can lead up to a C Major (C-E-G). All of the notes change. G Augmented (G-B-D♯) connects to C Major (C-E-G). The note G overlaps in both chords while the other two (B & D♯) move up a half-step to the next notes (C & E).

One More Thing…

So now we’ve seen that (1) all chords on any instrument can be described by a “formula”, (2) guitar chords can be grouped by root note position and moved along the fret board as a “shape”, and (3) chords consist of four basic types: major, minor, diminished, and augmented.

I also want to give you an edge on other chords you might see, so here we go!

Some chord names use 7 or △ in their name. If the name uses 7, then the degree is ♭7. If the name uses △m then the degree is 7. This is because chords like Cm7, C7, and Cm7♭5 are more abundant then C△. In order to create a short-hand naming convention a “7” is used in the name even though their formula’s are Cm7: 1-♭3-5-♭7, C7: 1-3-5-♭7, and Cm7♭5: 1-♭3-♭5-♭7. Only C△ uses the degree 7 with a formula of 1-3-5-7.

Another way to think of this is by the △ symbol. The △ is the “leading tone”, which is the name of the last degree possible before reaching 1 again. Anything that uses a △ uses the 7th degree as it is just before 1. Any other seven used in a named is a ♭7.

If you see a 6, then there are two options: the formula is 1-3-6 or it is 1-3-5-6. I tend to use 1-3-6 as it keeps the compressed notes of 5 & 6 from “rubbing” against each other. If you do see a chord like C6 using the formula 1-3-5-6, then it might actually be played in the form 1-3-6-5 where the 5th degree is a higher pitch than 6. This would give degrees 6 and 5 some breathing room and make it easier on your listener’s ears.

Degrees 9, 11, and 13 are just 2, 4, and 6 in a higher octave. Even if you see a flat or sharp 9, 11, or 13, these use the same positions as sharp or flat 2, 4, and 6. They do function a bit differently than 2, 4, or 6. So think of it like this: 2, 4, and 6 are found in the first octave between the first 1 and second 1. Any pitch that is a 2, 4, or 6 above the second 1, is actually a 9, 11, or 13.

Last part! A suspended chord like Csus2 or Csus4 uses degrees 1-2-5 or 1-4-5. In both chords the 3rd degree is moved to the 2nd or 4th position. That’s it.

Chords that add a note like Cadd9 use the formula 1-3-5-9. The 9 is like a 2 that is added in the next octave. Having a 3rd degree prevents the chord from being “suspended”. The same thing happens in a chord like Cm add11, with a formula of 1-♭3-5-11. In this chord, the ♭3 is the “third” and it is not suspended to 2 or 4. The 11 is like a 4 and is added as an additional note in the next octave.

As you come across a chord that you are not familiar with, be sure to look up its formula. That way you can understand it the set of degree it uses and how to create it. With the guitar you can then create a moveable shape. On other instruments you still have a “shape”. On the piano a Cm and Gm chord will have different shapes, but at least the formula is the same. As you learn more about music theory, these formulas will become the basis for any “shape” on any instrument. Now THAT is a pretty powerful concept.