The Sound of Flamenco Dancers

The Harmonic Minor scale is one of the dramatic backdrops used in Spanish guitar and dance. It has all the smoothness of the Natural Minor scale and includes a crucial note: the leading tone. A leading tone is the note just below the Tonic, which is our main note that our songs revolve around. Imagine in your mind that someone is playing a classical guitar with a flamenco flair for a few seconds. As you listen to this in your mind, take the time to “hear” the last note. Now hear it again in your mind, but this time add the leading tone just before the end, which is the next note below the end note. If you’re having a hard time imagining this, then check out this audio clip. The same melody will be used twice, but the end with differ. I’ll use E Natural Minor at the end of the melody first and use E Harmonic Minor in the second part.

I played this clip for my wife. She said that the first example sounded like a musical, while the second sounded like a horror movie. Both examples are exactly the same except for one note, which came right before the final note of each example.

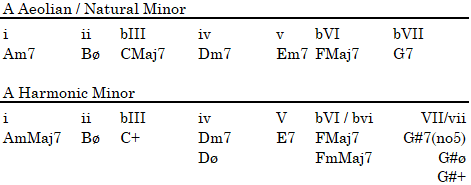

But this one change means much more. With a leading tone built into Natural Minor, or the Aeolian mode, we gain access to another set of sonic textures. The modes of Harmonic Minor may appear to be close to the modes of Harmonic Major. They are in some respects, so look for that one different note and what it does for us.

Comparing Aeolian to Harmonic Minor

I’d like to point out one issue before we dive into Harmonic Minor. As we describe scales and modes, we use the Major Scale as the standard for all scale comparisons. The Major Scale uses degrees 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. There are no sharp or flat degrees. Because of this we can describe a mode like Aeolian with a formula of “b3-b6-b7”. The degrees of Aeolian are 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, and b7, but focusing on the three flat degrees are all we need to describe Aeolian.

Harmonic Minor uses degrees 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, and 7. Therefore, we can think of Harmonic Minor as being a formula of “b3-b6”. The issue is that we are comparing Harmonic Minor to the Major Scale. Comparing Harmonic Minor to the Major Scale is like comparing apples and oranges. Harmonic Minor is minor. The major scale is not minor. To have a proper comparison, and usefulness of this scale, we need to compare minor to minor.

Comparing Harmonic Minor to Natural Minor, aka the Aeolian mode, fixes this in two ways. (1) We are comparing two “minor” scales. (2) There is only one degree that is different between the two scales.

Another way this is helpful is more conceptual. Aeolian is a mode of the Major Scale. This means that when we compare Harmonic Minor to Aeolian we are using Aeolian as a means to accessing the Major Scale. This is where Natural Minor comes into play. When someone says they are playing Natural Minor they are using Aeolian, but they are also putting the tonal center (Tonic) of the Major Scale on Aeolian. Doing this anchors the Tonic into a minor format, allowing us to easily compare the Major Scale as a whole to other minor scales.

The Modes of Harmonic Minor

The chart above takes the modes of Natural Minor and starts with a natural 7th degree to create Harmonic Minor. As we go through each mode, the altered degree (highlighted in red) is the same note in each mode. Using A Harmonic Minor we would have the notes A, B, C, D, E, F, and G#. The note G# is our altered note and will line up with each altered degree: A Aeolian’s b7 note G becomes G# which is A’s major 7th. This change travels through our Natural Minor modes to create the Harmonic Minor modes.

By the time we get to G Mixolydian we are still sharpening G, but G# Mixolydian #1 makes no sense. We cannot have a scale with an altered first degree, so G# Mixolydian #1 (#1-2-3-4-5-6-b7) is corrected by flattening every degree once to create G# Super Locrian bb7 (1-b2-b3-b4-b5-b6-bb7).

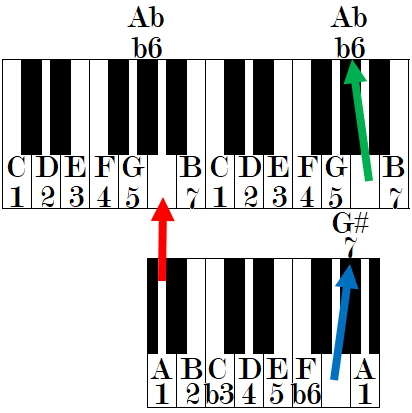

A Harmonic Minor may appear to look a lot like C Harmonic Major due to the note G#, but it is very different. C Harmonic Major is a major scale with flattened sixth degree creating Ab. A Harmonic Minor is a minor scale with a natural seventh degree creating G#. While Ab and G# may sound the same, they are two different notes representing two different degrees: Ab as the minor 6th of C and G# as the major 7th of A.

Brief Descriptions of Harmonic Minor Modes

Aeolian ♮7 (formula 1-2-b3-4-5-b6-7) is our first mode and should not be referred to as Ionian b3b6. Yes, the formula for this mode is “b3-b6”, but if we think of it as Aeolian with a natural 7th degree, then we can start using it as Aeolian with the leading tone. Aeolian’s main chords are the minor and m7 (or minor seventh). Raising Aeolian’s b7 degree to 7 (or major seventh) still lets us use a minor chord, but we can now access a mMaj7 (or minor major seventh).

Ending part of a song on a mMaj7 can give it a spooky film noir feeling. It also causes a sense of “unending” due to the major seventh working as the leading tone in a minor chord, but there’s a little more to the mMaj7 chord.

In the chart above we have a CMaj7 which is built using “alternating thirds”. A “third” is either a major third of two whole steps or is a minor third of a step and a half. In CMaj7 there is a major third, a minor third, and then another major third. Am7 is also built using alternating thirds, it just starts on a minor third.

AmMaj7 is quite different. From the note A to C we have a minor third, then we alternate to a major third from C to E. After that, we stop alternating thirds to use another major third to go from E to G#. This is where that tense feeling comes from. AmMaj7’s note of A-C-E make the chord feel like a minor chord, but the notes C-E-G# create an augmented chord. This means that all mMaj7 chords are minor chords that contain augmented chords within themselves.

Locrian ♮6 (formula 1-b2-b3-4-b5-6-b7) is a great mode for expanding on the diminished sound. Plain old Locrian is fine for creating half-diminished sounds with the m7b5 chord at its core. The natural 6th degree of “Locrian ♮6” expands upon the Locrian mode by add two more chords: the fully diminished chord (°7) and the minor six (m6).

B Locrian contains the chord Bm7b5. When we go to B Locrian ♮6 we can use a B°7, which is a great chord for creating tension. We also get a Bm6, which can feel like a Dorian chord due Dorian being a minor mode with a natural 6th degree. Minor 6 chords are important to be aware of because they are diminished chords in disguise. If you take a Bm6 chord and put it in second inversion, which means to take the third note of the chord and put it in the bass end, you get a G# diminished chord. This means that Locrian ♮6 contains a m7b5, °7, and a m6 as an “inverted diminished chord”.

These options not only expand on the sounds you can use, they also give you more ways to treat other notes like the leading tone. In Bm7b5, B is the leading tone. B°7 has four leading tones: B, D, F, and G#. Bm6 is an inversion of G#°, so Bm6’s leading tone is G#.

Next up is Ionian #5 (formula 1-2-3-4-#5-6-7). This mode helps create “access” to other modes that contain augmented chords. A C+ chord uses the notes C-E-G#. In A Harmonic Minor A is the Tonic and G# is the leading tone of A. This means that we can play all our favorite degrees from Ionian while avoiding the 5th degree. When we are ready, we can use C+ and the note G# to lead to Am. Try playing a CMaj7 no5 (which is C, E, B), and then the notes C, E, and G# one at a time, followed by an Am chord. This is one way we can use Ionian (CMaj7 no5), lead with C+ (C-E-G#), and arrive at our Tonic of Am.

Dorian #4 (1-2-b3-#4-5-6-b7) gives us a new way to brighten a minor mode while adding tension. The note G# in D Dorian #4 allows us to use half-diminished and fully diminished chords. What makes this mode special is that we get to keep the 5th degree. Doing so allows for all the great minor sounds of Dorian, but with a #4 as an equivalent to the b5 or as the #11.

Below we have some examples of chords in D Dorian #4. The last chord is a voicing of (or way to “sound”) a Dm #11. In this chord we use the 5th degree of D, which is A. Doing so prevents G# from sounding like a b5. To brighten the tension, I put D’s b3 note (F) and D’s #11 note (G#) in the second octave of the chord. Try out this voicing of Dm #11 in a progression like | Am | G | F | E7 Dm#11 | Am |. This Andalusian progression takes the downward movement of the root notes and instead of stopping at E7 and returning to Am, we keep going briefly and use Dm #11 to spice things up for half of the 4th bar.

The E7 chord we just used comes from E Phrygian Major (1-b2-3-4-5-b6-b7). This is very different from Phrygian b4, which comes from Harmonic Major. In Phrygian b4 we have the degrees b3 and b4. These two degrees help to create major and minor sounds from one mode. In Phrygian Major do not have minor sounds.

What we gain access to is a blend of dominant and augmented structures. Above we have E7 as a Dominant 7 chord, E+ as our Augmented chord, and E7 b13 as both. E7 b13 has all the notes of E7 to create “dominance”. By adding the note C we also have the notes of E+. The voicing above also spreads out the major third (blue) and minor third (red) intervals. While we do not have notes at two positions in this voicing, G# is the major third and covers the first “gap”. The other missing note is at the b9 position, which would be F. Playing this voicing of E7 b13 with a melody that uses F would make great sense because it “completes” the sound of Phrygian Major.

Lydian #2 (1-#2-3-#4-5-6-7) is a mode that adds “mystery” to our pallet of sounds. The #2 is equivalent to a b3, so we can now play Lydian with minor chords. What makes this mode sound mysterious is not the #4. Instead, the 6th and 7th degrees color this mode.

We can play FMaj7 in F Lydian #2 along with F6, FmMaj7, and F°7. Try playing a progression of Am (A-C-E-A) FMaj7 (F-A-C-E), F6 (F-A-D-F) which is an inversion of a Dm chord, FmMaj7 (F-G#-C-E), F°7 (F-G#-B-D), and then arriving at Am (A-C-E-A). You’ll notice that the F6 is where the transformation from major to minor happens because this is a Dm inversion. By playing FMaj7, and then F6 as a minor in disguise, makes the minor quality of FmMaj7 feel right and not an abrupt change from F major to F minor.

The last mode is Super Locrian bb7 (1-b2-b3-b4-b5-b6-bb7). Think of this as a mode that takes Locrian (1-b2-b3-4-b5-b6-b7) and flattens 4 and 7 again. The degrees 4 and 7 are special because they help us with Functional Harmony and are a TriTone apart. By flattening both degrees we get a b4 and bb7, which are still a Tritone apart.

This mode is incredibly useful because it gives us both diminished and augmented chords. Think of this mode as having all the tension you need packed into one mode. You can play G# as the leading tone of A and build diminished and augmented sounds that help drive you to Am.

What to Practice

We’ve talked about a lot of concepts in Harmonic Minor. Many of these concepts talk about tension. This should be no surprise because the note we created all this tension with is G# and is the leading tone of A. Try playing A Natural Minor as you normally would and then interject G# into any chord or mode. Doing so will increase tension and drive you harder towards the Tonic note of A. Every time you play A Natural Minor with G# you instantly gain access to the modes of A Harmonic Minor.

To keep up on practicing what we’ve already covered, try playing C Melodic Major (the C Major Scale) and use Ab to borrow some sounds from C Harmonic Major. Then use chords like G7, E7, Bm7b5, or even G#°7 to tonicize A. Now you can play A Natural Minor and start using the note G# to access A Harmonic Minor.

Below is a chart and a progression that uses this idea of moving the tonic note from C to A and using Ab or G# to use “Harmonic” sounds. Play around with these scales and modes to see just how far you can expand your pallet of sounds. If you have any questions, then please leave them in the comments below. Thanks for reading!