In the first three articles for the “Let’s Play Music” series we covered some basic chords, functions of those chords, and ways to start counting out rhythm. The next thing to do is to get into the modes of the major scale. Thankfully we’ve already been doing this. Each of the chords we’ve used is part of the C Major Scale. In turn, each individual chord represents one of the seven modes of the Major Scale. In this lesson we’ll take what we know with the chord formulas that we practiced in the first lesson and start comparing them to the seven modes of the major scale.

If any of this looks difficult, then grab a pen and paper and take notes. You’ll learn much faster by writing out these formulas over and over. All of this will be drawn out for you at the end of the lesson, but don’t rely on diagrams. It’s better to learn one or two formulas a day and slowly add to that.

Each topic in this lesson will be used to build into the next one. We’ll also be coming back to these concepts in future lessons, so don’t feel like you need to master all of this right away. Absorb what you can, take notes, and practice. Now let’s get into it!

A Brief Overview of the Chromatic Scale

If you're new to music, then I don't expect you to memorize the Chromatic Scale right away. It is worth going over because every other scale or mode can be compared to it, which is why I wish that I knew about this scale when I was first learning about modes. The Chromatic Scale contains all the degrees in music. If we start on C, then Db is C's minor second. The next note up is D, which is C's major second. However, if we start on D, the note Eb is D's minor second and F is D's major second. Using degrees to describe chords and scale makes it easier to understand as each degree will give a particular sound. If I play a Maj7 chord, then my degrees are 1-3-5-7, but it doesn't matter where we start as far as notes go. If we use the right degree notes, then we will always have a Maj7 chord. CMaj7 is C-E-G-B and DMaj7 is D-F#-A-C, but the degrees used in both chords are 1-3-5-7.

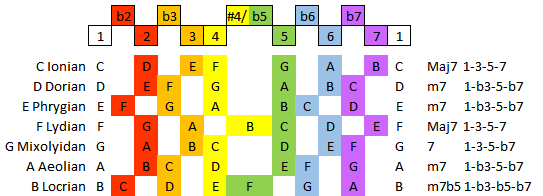

The same is true for the Major Scale, which uses degrees 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. Looking at the chart above, the Major Scale uses the tonic note, major degrees, and perfect degrees. None of the minor, diminished or augmented degrees are used, yet they can still be accessed through the modes of the Major Scale.

Another thing to keep in mind is that degrees come in sets, which are shown by the colors in the chart. Yes, the first degree is by itself because it is the “anchor point” that helps us to define the other degrees. Without the first degree there can be no higher degrees. Beyond the first degree we have a pair of 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th degrees. Now you might be looking at the overlap between the #4 and b5 degrees. Think of it like this: the “perfect” degrees share the “augmented” or “diminished” degree between them while the other degrees are simply “major” or “minor” degrees. These pairs line up perfectly with the C Major Scale as shown below.

What is a Mode?

Think of the seven notes of the C Major Scale and start with C as the first note. The intervals, or spaces, between each note from C to C would give you the Ionian mode. Starting on D as the first note and moving across these same notes would give you the Dorian mode because of the combination of intervals from D to D. In the chart below there are seven modes. In each one the notes are the same: C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. The differences between each mode can be seen below as we notice that the half-step intervals are found in different locations in each mode.

In the next chart we have the same modes, but the first note is treated as the first degree. When we play a mode or scale the first note is the tonic note. This means that all other notes move towards that note. It also means that every other note is a degree above the tonic note. For example, in the C Major Scale the note C is the tonic note of the C Ionian mode, but it is also the minor second of B Locrian, the major second of A Aeolian, the perfect fourth of G Mixolydian, the perfect fifth of F Lydian, the minor sixth of E Phrygian, and the minor seventh of D Dorian. The function of the note C is defined solely by the tonic note of each mode.

This is true for all notes, which is why the Chromatic Scale is so important. By thinking about notes as the fifth of something, like G is the fifth of C, then we can start to see how all notes are a degree of another note. Imagine playing C Ionian, but you accidentally play Ab for a moment. The note Ab is the minor sixth of C. While it is not part of the C Ionian mode, it does belong to C as its minor sixth degree, so if you like using that note then you can remember that a b6 mixed in with Ionian sounds interesting. If you're wondering why I picked b6, it is because the Harmonic Major scale uses degrees 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, b6, 7. We'll get into that scale later, but it's good to know that there are other scales out there with their own flavors because notes are degrees of other notes.

The Mode – Chord Connection

Earlier I talked about chord formulas, like a Maj7 is 1-3-5-7. Looking at the chart above there are only two modes that use all four of these degrees: Ionian and Lydian. The only difference between these two modes is that Ionian has a perfect fourth and Lydian has an augmented fourth. This means that if you are playing a song with a Maj7 chord and the melody uses the perfect fourth degree, then you are in Ionian. If the melody uses an augmented fourth, then you are in Lydian. If neither of these degrees are used, then you will reply on another chord to help you find your place.

Before we start looking at the order of chords, let's take another look at the degrees of each mode along with some chord formulas. Below we have the same modes with the formulas for the seventh chords found in each mode. Two modes contain a Maj7, three modes use a m7 (minor seventh), one mode has a 7 (dominant seventh), and one mode has a m7b5 (minor seven flat five, also known as a half-diminished chord).

The next time you play a song, look at the chords. The major triads can fit into any mode with a major third and a perfect fifth. Minor triads fit with any mode with a minor third and a perfect fifth. Diminished triads belong to Locrian because it is the only mode with a minor third and a diminished fifth. Augmented chords do not belong to any of these modes because none of them have a major third and an augmented fifth, which is enharmonically equivalent to the minor sixth. This means that any augmented chords must belong to a mode from another scale like Harmonic Major.

Learn Modes the Easy Way

So far, we have been playing our modes in the order that they come in. But there is another order that will help you to better understand how each mode is related to the next. To do this we'll use the circle of fifths for a moment.

Below is the circle of fifths. Each note is a fifth apart. Looking at our previous chart we can see that C is the fifth of F, G is the fifth of C, D is the fifth of G and so on. Looking at only the notes we are using of C, D, E, F, G, A, and B we can focus on just part of the circle. Next, we can put the name of each mode over its corresponding tonic note to get F Lydian through B Locrian. Doing so gives us some interesting groupings. All our major modes are together, followed by the minor modes, and ended with our diminished mode.

With the modes organized in fifths we can now look at our previous charts and see that another interesting pattern emerges.

Starting with Lydian we have a #4 as our only accidental (note or degree that is sharp or flat). Ionian is the same thing as Lydian, but with a natural 4th degree. We can continue to see the single degree changes as we look at Mixolydian as the same thing as Ionian with degree b7. These single degree changes keep going all the way through into Locrian.

We can also look at these changes as their own pattern. By starting with Lydian and flattening degrees. Flattening the 4th and 7th degrees takes us through Lydian, Ionian, and Mixolydian. Flattening the 3rd and 6th degrees takes us through Mixolydian, Dorian, and Aeolian. Flattening the 2nd and 5th degrees takes us the rest of the way through Aeolian, Phrygian, and Locrian. Each pair of numbered degrees flattened was just to the left of the previous numbers: 2 and 5 are to the left of 3 and 6, which are to the left of 4 and 7.

By practicing each mode on their own we can change just one note/degree at a time hear the differences between the modes. Try playing a CMaj7 chord and then a C Ionian melody over it using the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. Then play a CMaj7 chord followed by a C Lydian melody using the notes C, D, E, F#, G, A, and B. Since Lydian is just Ionian with a #4, we need to take Ionian's fourth degree note of F and sharpen it to create C Lydian. The above chart has the formulas of chords along with the modes. Keep playing chords that are found in two modes and then a melody to hear the differences.

Another example of this would be a minor triad like Dm (D minor). We can play this chord with the notes D, F, and A and then play a D Dorian melody with the notes D, E, F, G, A, B, and C. To play a D Aeolian melody with just need to flatten the 6th degree and use D, E, F, G, A, Bb, and C. To use a D Phrygian melody, we also flatten the 2nd degree and use D, Eb, F, G, A, Bb, and C.

What to Practice

We’ve covered quite a lot today, so let’s review and go over what to practice.

This chart has everything that we’ve discussed along with the formulas for these modes on chords that we have already been using. The top section lists the formulas for each mode, why they are major, minor, or diminished, and has the chords that match each mode along with their formulas. The next section puts the modes in parallel, which just means that the same notes is used as the tonic note for all of them. The parallel modes we’ll practice with are C Lydian, C Ionian, C Mixolydian, C Dorian, C Aeolian, C Phrygian, and C Locrian. The last section is what we’ve been playing so far. These are the modes found in the Key of C which are C Ionian, D Dorian, E Phrygian, F Lydian, G Mixolydian, A Aeolian, and B Locrian. I’ve ordered the relative modes to match the parallel modes to make hearing the differences easier for you.

To practice the modes, you should break all of this down to just one mode at a time. Start with Lydian and play a CMaj7 chord followed by a melody that uses the notes in C Lydian as shown above. This chart matches the piano, so I’ve included guitar charts below. Next, play an FMaj7 and then a melody from F Lydian. Pay attention to the note that is your augmented fourth. For C Lydian this is F#. For F Lydian this is B. As you play your melody count out the degrees. The note names are important, but the degrees take precedence. By knowing your degrees, you will know the sound of that mode.

Once you are confident with Lydian you can move on to Ionian. All we do is go from an augmented fourth to a perfect fourth. Now play a CMaj7 and a C Ionian melody and notice the difference between Lydian and Ionian. Practice these two modes as much as you need before moving and be sure to continue to practice what you’ve learned.

Next, play a C7 with C Mixolydian and G7 with G Mixolydian. Continue this process with C and D Dorian, C and A Aeolian, C and E Phrygian, and C and B Locrian.

Ultimately this practice routine will become the chart above where you play all of the modes in parallel forward and backward followed by all of the modes in a relative set forward and backward. Be sure to call out the degree names in your head or out loud. Knowing the degrees of these modes will set you up to learn any mode or scale from here on out, so take your time and write them out repeatedly. Draw these diagrams yourself and remember that every five minutes of practice a day is better than five hours of practice a week.