Why Do We Enjoy Music?

For me, music is most enjoyable when it is engaging and makes me say, “What was that?” I don’t have to say it really, but the sentiment is definitely there. It could be the hook of a song or a drum groove that grabs hold of me. I’m sure that’s how it is for you. Your favorite songs likely have a part where the harmony and rhythm sync up perfectly. These songs can be fast, slow, easy going, hard and heavy, or any other way you might describe great music.

An element of music that I feel is often overlooked in today’s world of download singles and weekly top ten hits is chromaticism. This concept can be thought of as “all of the colors in music.” Imagine singing along with your favorite song, but instead of singing it exactly as it is recorded you opt to sing a few notes that don’t belong. These extra notes sound great to you.

This means that they work with the notes of the song. In fact, every note works with every other note. Some combinations sound perfectly balanced, while others can create a clash that can be a bit off-putting. Instead of thinking of notes that sound good or clash, we should think of these notes as being sonic textures. There is no good or bad when it comes to music. Now we have choices. We can choose to sing a soft melody, belt out a harsh set of lyrics, or find a middle ground.

In this lesson we’ll look at the middle ground so that we can find useful ways to use any note in music. By doing so we will see that a beautiful song can be a combination of things that don’t seem to fit together yet create interesting results that can captivate our imaginations. Like the water and oil in a lava lamp, chromaticism helps us create oddly beautiful things.

Going to Strawberry Fields

In the song “Strawberry Fields Forever” by The Beatles we get great chromatic movements that use ten out of twelve possible notes. This song is in the key of Bb which uses the notes Bb, C, D, Eb, F, G, and A. The chromatic notes used are Ab, B, and E. Take a quick look at the basic structure of the first fourteen bars of the song below.

I’ve color coded them for a few reasons: (1) each colored section can be thought of as a phrase, (2) the blue and green sections have the same amount of 4/4 and 2/4 measures (or bars), and (3) the yellow section takes us to a bar of 3/4 timing and then back to 4/4.

In bars 1 and 2 we have F played as F-A-C-F. The second F note then moves down to a chromatic note of E to create FMaj7 played as F-A-C-E, which is followed by F7 played as F-A-C-Eb. This is our first chromatic movement and is a great way to give the listener of the song an expectation of the unexpected in just the first two bars.

In bars 7 and 8 we get Fm7, which uses the notes F-Ab-C-Eb. Ab is a borrowed note and adds more chromatic flavor to the song. But why use Fm7? In the back half of bar 4 and through bars 5 and 6 we have Bb major droning on. Since a major triad like Bb major isn’t a Maj7 or Dominant 7 until we play it that way, we can hear it as possibly being both. Well Bb is the IV of Fm7, so Bb to Fm7 gives us a type of plagal cadence. Remember, a plagal cadence goes from IV to I to end a phrase. This time we go IV to i and we start a new phase. Again, as the listener we should be expecting the unexpected.

Bars 9 and 10 use G7, which uses the third chromatic note of B. G7 normally leads to C in a V7 to I relationship. In previous lessons we talked about moving the diatonic chords of a key a minor third up to get new flavors of the same chords from a related key. This simply means that the chords in the key of C can be swapped for the chords in Eb because Eb is a minor third above C. Bar 10 takes us from G7, but instead of going to C we go a minor third up to Eb in bar 11. In this way we can think of bars 10 and 11 as meaning to be G7, C, F, G in a V7, I, IV, V progressions. By moving C, a minor third up we get G7, Eb, F, G which is now heard as a V7, borrowed I, IV, V progression.

In bar 13 we then return to Eb as a Maj7 chord. A Maj7 can be the I chord or the IV chord. While it was played as a borrowed I in bar 11, it is now the IV chord of Bb which is played in bar 14. Adding in the 3/4 timing to bar 13 allows Bb to arrive earlier than expected in bar 14. Thankfully Eb to Bb was the end of the first phase, so Bb feels like it should have been the tonic all along.

Imagine if this song was written with only diatonic chords in mind. The chords BbMaj7, Cm7, Dm7, EbMaj7, F7, Gm7, and Am7b5 would be the entire pallet of sounds to us. Just three added notes allowed FMaj7, Fm7, G, and G7 to draw out new sonic flavors that created new emotions. We even got to hear the Eb chord as both the I chord and IV chord, which implied that it could belong to the key of Bb or the key of Eb. A little change from Eb Lydian to Eb Ionian went a long way.

Take Your Playing to the Next Level

Whenever I am writing a song I start with a few chords. Even two chords can be a great starting point. After that I am thinking about options. Take the key of C for example, which has the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. We are missing Db, Eb, F#, Ab, and Bb. To put these notes to use we could borrow from relative and parallel modes like we’ve done in previous lessons, but why not do something new?

Rather than “borrow” notes and chords from other keys I’ll add in a note or chord just because I like the sound of it.

Starting with the key of C I’ll add in E add9 and play a vamp of C Maj7 & C add9 with E add9. The E add9 chord can be borrowed as the V/Am, which would allow an E Mixolydian melody to be played over E add9. I don’t want to borrow anything this time. Instead, I want an “airy” quality from E add9 so I’ll use E Lydian over the E add9 chord.

By using E Lydian instead of E Mixolydian we gain quite a few chromatic notes. Looking at the chart below we can see that E Mixolydian has three chromatic notes for what I am playing in the key of C, which are F#, G#, and C#. Using E Lydian adds in two more chromatic notes, which are A# and D#. It might look like we are completely changing the key, but what I am doing is creating options. I have the “option” to use F#, G#, A#, C#, and D# as chromatic tones in the key of C.

When I play E add9 the notes I play are E-G#-B-F#. These notes fit both E Mixolydian and E Lydian. To make my melody sound like it is Lydian I’ll focus on degrees #4 and 7 which are the notes A# and D#.

A two bar melody using the sequence of notes D#, E, C#, G#, and A# over E add9 as shown below does two things. (1) it uses plenty of chromatic notes outside the key of C and (2) it ends with G# moving up to A#.

In the next two bars I’ll play CMaj7 which contains the note B and C add9 which uses the note D. This way I can use voice leading to allow the G# to move through A# and then B in the CMaj7 chord to continue up to D in the C add9 chord.

There are so many options out there that it can be a bit daunting to try to use chromaticism without a road map, so here’s one that I think will help you out.

The Circle of Modes

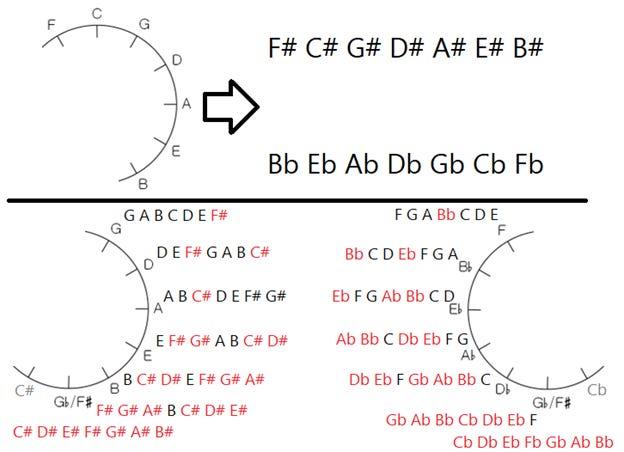

Instead of trying to figure out all of our sharp and flat notes to find keys, modes, or chords we can use a concept built into the Circle of Fifths. Starting at the top of the circle and going clockwise adds sharp notes while going counterclockwise adds flat notes. The concept we will use is that as we go clockwise we also sharpen our modes and as we go counterclockwise we flatten our modes.

If we continue to move in a sharp direction past Lydian or a flat direction past Locrian, then we start the list of modes over with our root note being sharpened or flattened. Check out the diagrams below for a visual on how this works.

Also, please note that the bottom three keys of Db/C#, Gb/F#, and B/Cb are the only keys that allows for flats and sharps. All other keys aside from C have either sharps or flats only.

When I used E Lydian in the key of C I started with E Phrygian because it is the third mode of the key of C. Going from Phrygian to Lydian sharpens the mode five times, so I can go around the Circle of Fifths in a sharp/clockwise direction for five keys to go from C to B.

Going five keys around the circle in a sharp direction also sharpens five notes. Using the portion of the circle that has natural notes we get an order known as “the order of sharps and flats”. As we move around to the sharp side of the circle we gain one sharp note at a time. The first key in the sharp side is G and has F# as the sharp note. Next is the key of D with F# and C#. The third key is A with F#, C#, and G#. Starting to see the pattern? This works in the flat side of the circle with the Key of F using Bb, the key of Bb using Bb and Eb, and the key of Eb using Bb, Eb, and Ab.

Modal Formulas

Another thing I like to do when writing a song is take a few chords and use a mixture of modes and scales that fit those chords. The classic ii-V-I is a great example. Using Dm7 to G7 to CMaj7 we can play melodies within D Dorian, G Mixolydian, and C Ionian. Thankfully these chords are not limited to these modes. For example, a Dm7 can be from Dorian, Aeolian, or Phrygian from the modes of the Major Scale. But what about other parent scales?

Harmonic major can use a Dm7 in Phrygian b4, Harmonic Minor can use Dm7 in Dorian #4, and Melodic Minor can use Dm7 in Dorian b2. This is because a Dm7 uses the degrees 1-b3-5-b7 and this formula is part of the degrees of Dorian, Aeolian, Phrygian, Phrygian b4, Dorian #4, and Dorian b2.

We can do this with any chord or arpeggio we want including suspended chords, extended chords, and chords that omit degrees like CMaj7(no 5): C-E-B.

Below is a chart of modes from four parent scales and some chords with the degrees they use. Try out some of your own combinations to see what you think sounds interesting. There are no right or wrong choices. There are only flavors of sounds that you can mix like sonic paint.

If you have any questions, then please let me know in the comments section. I’m always happy to help. Thanks for reading!