What is a Voice?

Before rock & roll, country, and jazz we had classical music as the main genre. A long time ago the venue for music was mainly churches and singers were treated as instruments. Composers using vocals would have to use multiple singers to create chords and in doing so had to make each singer’s vocal melody sound good to the audience while also being simple to sing.

Thinking of each note as a “voice” can help us to see how the techniques of Voice Leading can treat notes as individual roles. A composer with only three singers can do a lot for an audience if they know how to keep each singer within their own range, in a simple set of notes, and with enough space to let each singer be heard.

There are times when we do not need Voice Leading and should avoid it like in genres such as metal and punk rock. Knowing when to not “lead” a voice in a phrase can allow you to make melodies stand out in the following phrase. To do this we’ll look at some of the techniques of Voice Leading and use them in practice so we can have another tool in our musical belt.

Please keep in mind that this will not be a dogmatic approach to voice leading. There are degrees that people earn on this subject alone, so to make this lesson useful we’ll focus on rules that we can use. In this way the “rules” as options rather than rules being “absolutes” or “laws”.

A Few Simple Rules for Voice Leading

There are many rules that can be used in Voice Leading. Since this is an introduction to the concept, I will be sticking to some basic rules, so you don’t get overwhelmed. As we discuss this topic, I will be using the term “voices” to help describe notes as they move from one pitch to another.

#1: Retain common tones.

The notes of the chords C major are C-E-G and the notes of Am are A-C-E. In both chords we have the notes C and E, so they are common tones. We want to keep one or both notes as we allow our voices to move. A simple example would be to play C, C+, Am. In this progression the “voices” C and E play their parts in each chord. The single voice of G goes up to Ab to create the C+ chord and up again to A to make a C6 chord. C6 is an inversion of Am, so this is a great way to lead a single voice while retaining common tones. But there are some other rules to consider.

#2: Avoid parallel fifths and fourths.

A “fifth” is three and a half steps between two notes. Common chords that use this are major and minor chords because both chords have a root and a perfect fifth. Using just chords that use two notes can sound great in rock music, but the melody gets lost because of the parallel movement. Think of two notes like C and G on sheet music followed by A and E. There are only two voices: C moves to A and G moves to E. As these voices move up or down, they are parallel to each other and cause the melody to become stagnant.

If we did the same movement, but with a perfect fourth, then we are using an inversion of a perfect fifth. Think of the notes C and F. With C as the root note, F is the perfect fourth. If we invert the order, we get F as the root note and C as the perfect fifth. In this way we can treat a perfect fourth interval as an “inverted fifth”. To avoid parallel fourths, we can start with the voices C & F. C moves up to F and F moves up to C. The interval went from a fourth or “inverted fifth” to a “natural fifth” and avoided the movement of parallel fifths and fourths.

To avoid this further, we can use a major or minor chord, but follow it with something that does not use a fifth degree note. C major played as C-E-G-C followed by Dm7b5 played as D-F-Ab-C works great because the perfect fifth interval used in the first and third voices, C and G, become a diminished fifth as D and Ab (grouped in red). The fourth voice in the C major chord is a common tone in both chords, so that voice remains the same (shown in blue). The second voice goes from E and up a half-step to F (shown in green), which is what we need for the next rule.

We can also opt to drop the fifth degree completely. Chords in Jazz that do not use the fifth are known as “shell voicings” because they are just the outer portion of what is needed to make the chord. Playing CMaj7 as just C-E-B uses the root, major third, and major seventh and has all the qualities of a CMaj7. We can do the same thing with Am7 and just play A-C-G.

Parallel movements can also happen when we move from a Maj7 to a Maj7 or from a m7 to a m7 even if we drop the fifth degree. The major third and major seventh degrees are a perfect fifth apart. A minor third and a minor seventh are also a perfect fifth apart. This means that moving from CMaj7(no 5) to EbMaj7(no 5) or Dm7(no 5) to Em7(no 5) will have parallel fifths.

If this happens to you, then try moving the third degree to the sus2 or sus4 position. A movement like CMaj7(no 5) to EbMaj7sus2(no 5) sounds complicated until we just talk about the voices of C-E-B moving to Eb-F-D. There are many ways that we can direct our voices to go from one set of notes to the other and we will avoid parallel fifths no matter what we choose to do.

#3: Move voices by a major third or less, with less being the best movement.

There is a common saying that “notes like to move as little as possible”. This doesn’t mean that you can’t move a note more than a half-step at a time. It simply means that gentle movements of voices can help strengthen harmonies. Playing four bars of triads like | Am | G6sus4 | F6 | Am | can move our voices gradually, but with effectiveness.

In the above diagram common tones are shown in blue, whole steps are in red, half-steps are in pink, and the major third movement is in green. This progression allows the voices to use common tones, avoid parallel fifths, and keeps all the movements at a major third or less. Notice how the top two voices start in Am as C and E. They continue as C and E in G6sus4, lower briefly for the F6 chord, and then return to C and E in another Am chord.

The voice with the most movement is the lowest one, which is the root note of each chord. By moving the root note we can redefine the notes C and E as the minor third and perfect fifth of A and transform them into the perfect fourth and major sixth of G. As the root lowers further in F6, we then allow the top two voices to descend before returning to where they started. As they return to C and E, the root note then comes up to A to let the top two voices act as the minor third and perfect fifth. By ending on a simple triad that has no suspensions, tritone intervals, or leading tones we solidify our four chord phrase with a solid ending.

#4: Change the register for long chord durations or new phrases.

A “register” is a range of notes that is typically notated as soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. Each of these registers covers a specific range of notes. To make this rule useful, think of a register as approximately two octaves. There’s a lot of space for a chord and a melody to fit in within two octaves. This space also keeps us grounded in a range that is a bit more workable because most notes will only occur twice.

From C up to C is one octave. Add the next C note and we have two octaves. Within those two octaves we have three C notes, but every other note only occurs twice. This means that if we want to use the 4th degree note of C we go to F in the first octave or F in the second octave. We no longer need to consider every note when creating melodies. We can focus on what we want, like the 4th degree note of F, and then chose which of only two options sounds best.

When we get to a chord or phrase that is played for a while, we can then change the register. This means that we can shift our two-octave register up or down several octaves to escape the monotony of using the same note range.

Imagine playing a progression several times for a verse that ends in Am7 down a whole step to G7 and then ascending to C. When it is time to switch to the chorus we play the G7 two octaves higher than before and then descend to Cm. This huge jump in register for the G7 makes it stand out as if to say, “And now for something different.” Since we’re creating change, using G7 as a secondary dominant of Cm (V7/i) makes sense. When we are ready, we can then take G7 from a higher register/octave and bring it back down two octaves. Doing so states to our listener that “change is happening” and we can then take this lower G7 to our C chord once more.

#5: Focus on target notes.

We are not just leading our voices. We are also “leading to something”. That something is whatever comes at the end of a phrase, line, or even the song itself. Playing G7 to C isn’t just a good use of a V7 to I. It’s also a cue to us to know that we are resolving the tension of G7 to the three notes in C: C-E-G.

We can use these three notes as target notes for our melody to move to. Imagine you are playing with someone and all they have is an idea of a song with several chords from the C Major Scale. The last two chords are G7 to C. Now let’s make only two assumptions. #1: The melody from G7 to C needs to start with F because it is the b7 of G and creates the dominant quality of the chord. #2: The melody needs to end on C, E, or G because they are the notes of the C major chord.

Now grab your instrument and play G7 to C nice and slow a few times. Next play G7 followed by any melody that starts with F and moves to either C, E, or G. When you get to that final note of C, E, or G, play the C major chord in its place. Listen to how taking one of the notes of the G7 chord, like the tension note in G7, and moving it to a target note helps to complete the phrase.

Each target note gives the melodic phrase its own feeling. Moving to C creates rest and makes the melody feel at rest with the tonic note of C. Moving to E also creates rest but touches on the note that makes the C major chord “major”. Moving to G uses the perfect fifth of C and adds brightness.

Listen to the audio example below for the same melody starting of F, but ending the melody with the notes C and C, C and E, and then C and G. You may hear other things besides “rest” and “brightness”. Let me know what you hear in the comments section.

Putting Voice Leading to Use

Imagine strumming a guitar (or playing the instrument you have) and finding a few chords that you like. Something simple, like |: G |C |G |C |G |C |Am7 |D7 :|. This can be thought of as |: I |IV |I |IV |I |IV |ii |V :| in the key of G. It sounds good, but it’s just some chords. There’s no melody. There’s no movement. But we do have plenty of parallel fifths. So where do we start to make this sound better?

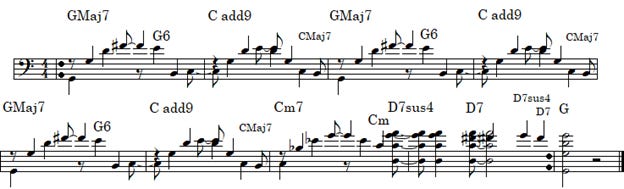

I would start with the vamp between G and C. These are triads and have three voices, while the Am7 and D7 have 4 voices. Since we are in the key of G, let’s use GMaj7 and C add9 so that each chord has four notes and therefore four voices.

Both GMaj7 and C add9 use the note D. This will help us satisfy our first rule of retaining common tones. We can also use D as a note to continue to visit and thus make it a “target note” that our melodies move to and from.

To recap, we now have GMaj7 as G-G-D-F# and C add9 as C-G-D-E.

We can avoid some parallel fifths by having the middle two voices remain in place so that they do not move with the bass voice. D is the fifth of G and G is the fifth of C, but our middle two voices of G and D act as our “fifth degree notes” and do not move. Now we can move the bass voice to and from G and C and have no parallel movement between the bass and the inner voices.

To add movement, we can look to our highest voice. In GMaj7 that is F#. We can lower it to E and temporarily turn our notes from GMaj7: G-G-D-F# into notes from G6: G-G-D-E.

As we go from a root note of G to C we are moving up a perfect fourth. Rule #3 has us move by a major third or less. To make this work for us I’ll take the root note voice from G to B and then up to C. As we return from C to G I’ll have the root note voice stop by at B as well.

B is the major third of G, so it fits with GMaj7 and G6. B is also the Maj7 of C, so as we go from C add9 to GMaj7 we briefly use the notes of CMaj7.

We can use the above movement in our vamp, which means to go back and forth between two chords for several bars or more. Think of a jam track that just plays C major and Am for ten minutes. That is a long vamp.

In the next chart we have the same melody, but our four voices are connected by colored lines. Notice how the red and green voices never change their note. Only the blue bass voice moves along with the higher orange voice, which the orange voice only moves in bars one and three.

Now we can focus on Am7 and D7. I’ll start with D7 because it is the dominant chord that leads us back to our tonic note of G. Whenever I want to brighten a tense Dominant 7 chord, I’ll usually use a sus4. D7sus4 uses the voices D-G-A-C, with a sus4 note of G, so it uses the tonic as both a “brightening” note and as a common tone between D7sus4 and GMaj7.

Rule 4 wants us to use another register when we stay with a chord for a while or move to a new phrase. The sus4 note of G in D7sus4 can move a whole step up to A for a moment to double up on the fifth degree note to start extending beyond the two octaves that we’ve been using, which helps us to briefly touch a third octave and thus a higher register. We can then return to GMaj7 or move to something else for another phrase or section of our song. We can also play a D7 chord on the guitar in the fifth position and gain that higher A note as well, so I’ll go for that style of voicing for a D7 chord.

All that’s left is the Am7. There are a lot of options like A7sus4 or Asus2, but I felt like we needed some more drama here. A cool borrow that we haven’t talked about yet is to move a chord up a minor third. The way this works is Am is our ii chord in G major. We “daisy-chain” from G Major Scale to G Natural Minor as the parallel minor. We then “daisy-chain” one more time from G Natural Minor to it’s relative major of Bb Major Scale. The ii chord in Bb Major is Cm, so we replace Am7 with a borrowed ii chord of Cm7. Again, all we really did was move Am7 up a minor third to Cm7, so if that helps you remember this concept then stick with that for now.

To help tie Cm7 in with D7sus4, I’ll take the voice using the note Bb as the b7 and raise it up to C. This way Cm7 becomes Cm with two notes of C. The root note C will move up to D, but the other C note will stay in place and become the b7 of D7sus4.

I’ll add in one more movement right at the end by moving our third voice, which is the note G in D7sus4 and F# in D7. I’ll have this voice briefly return to G and then F#. Doing so brings back D7sus4 for a moment, but it also highlights the tonic note of G and G’s leading tone of F#. Then we can move on to resolve to any G major chord.

While this isn’t perfect voice leading, it is a great improvement that adds a lot of melodic movement with only four voices.

What to Practice

The point of this lesson’s exercise is to focus on the five rules we discussed.

#1: Retain common tones.

#2: Avoid parallel fifths and fourths.

#3: Move voices by a major third or less, with less being the best movement.

#4: Change the register for long chord durations or new phrases.

#5: Focus on target notes.

Take some time to pick out a few chords. They can be from one key or have all kinds of borrows and modulations. Write down the chords and the notes used from lowest tone to highest. You may want to write them out vertically on a sheet of paper so that C major is C on the bottom, E in the middle, and G up top. Write out all the notes for your chords in letter form like the example below and leave some space.

Now find issues with your progression by reviewing the five rules. As you move the voices to make new chords, melodies, and arpeggios write out what is moving like in the next example.

Now play what you created. What do you like about? What needs improvement? Are there still parallel fifths, but it sounds good? No matter what you come up with remember that voice leading is not a set of absolutes. Voice leading is a concept of rules that helps guide us away from pounding out chords and draws us into a world of natural melody. If you want to break the rules, then go for it. That’s what music theory is really all about.

Please leave any questions you have in the comments and have fun. Until next time.