Playing by Ear

Have you ever met someone that plays a musical instrument that could hear a song and just start playing it? People who don’t know anything about music are usually amazed and can think that the performer is incredibly talented. While talent can help, other musicians know what is really going on.

The performer uses a technique called “active listening” where you listen for specific elements of a song. By listening for the tonic note you can then start to call out scales, chords, and melodies that are related to the tonic note. This may seem like something that takes years to learn, but that isn’t the case. We can learn the basics of this skill quickly. Mastering it is what takes time and is equal to the effort put into learning this skill.

Where is the Tonic?

Pick a song that you want to learn. It’s now time to grab your instrument or download a piano app to your phone so we can figure out what the tonic note is. The main parts of any song tend to be the verse and chorus, so let’s focus on those sections. The verse usually comes first and may repeat which gives us an advantage because we can listen for the verse to end on the tonic twice. Listen for the last note of the verse. This can also be the root note of the last chord of the verse.

We can also listen to what the lyrics end on. Songs like “I Won’t Back Down” by Tom Petty make the tonic note crystal clear. The lyric, “stand my ground,” uses the notes D, B, and G in that order. This does two things for us. It tells us that the melody leads to G, so G is likely the tonic. The other use of these notes is that a G major triad uses the notes G-B-D. This means that the lyrical melody literally spells out a G major triad. Since each repetition of the verse section ends with the G major setup, we can say that we are in the key of G.

To confirm this, we are given the notes A, D, G with the lyrics “won’t back down”. This is a classic ii-V-I progression where A is a fifth above D and D is a fifth above G. But how do fifths help us?

The Oh-Yeah Cadence

When part of a song ends, like with “And I… won’t… back down,” the end chords create a cadence. This can be thought of as a melodic punctuation mark. Since this is the end of a “musical sentence” we can look for the tonic note at the end.

Every note has a note that is a fifth above it. Try playing G and then C. G is the fifth of C and gives the sound of “Oh-“with the fifth and “-Yeah” with the tonic. This is known as a perfect cadence when going from the fifth up to the tonic or an authentic cadence when going from the fifth down to the tonic. But if someone just calls it a perfect cadence then let them. Knowing that a five-to-one works “perfectly” is the important part.

The fifth degree chord in a major key is major and the fifth degree chord of a minor key is minor, so no matter what type of key we are using we can go up a fifth and try out a second chord to see if it works. It doesn’t have to be part of the verse or chorus. The fifth just needs to work with the tonic because it is one of our constant chord functions.

The fifth degree chord is so prevalent that no matter which type of key we have (major or minor) we can always play a dominant chord from the fifth degree. This means that G7 is the fifth of C major and C minor. If you are confident that you are in a minor key, but the fifth is definitely a dominant chord, then that is great. A chord like G7 is not part of the key of C Natural Minor, but it is a typical borrowed chord that is used so often in minor keys that we can consider it as one of our diatonic chords.

The Ah-Men Cadence

There is another cadence called the Plagal Cadence. This is where we take the fourth degree chord and move to the tonic chord in a major key. In major keys the fourth and tonic are both Maj7 chords. In minor keys the fourth and tonic are both m7 chords. The trick with this is when we move from a minor four chord like Fm7 to a major tonic chord of CMaj7. This makes a “minor plagal cadence” and is typical of love songs, ballads, and songs that end with a little extra touch of relaxation.

Back to the Circle

By knowing the tonic note, or the note that a song moves towards, we can mark it on the circle of fifths. If C is the tonic, then the fourth is F and the fifth is G. Notice how the fourth and fifth are next to the tonic on the circle. In Tom Petty’s song the tonic is G, so C is the fourth and D is the fifth. Now we have three notes and at least three chords just by knowing the tonic.

Remember that in major keys the tonic, fourth, and fifth are all major chords while in minor keys they are all minor chords. In C Major the chords are CMaj7, FMaj7, and G7. In C minor the chords are Cm7, Dm7, Gm7, and possibly G7. Again, this works for any tonic note for all major and natural minor keys.

Using the Third Degree

Many great songs can use modulation and make the fourth and fifth degree chords major or minor for a variety of reasons. To help confirm the key you are in try playing the third degree chord.

In a major key the major-third is a half-step down from the fourth and is a m7 chord. In minor keys you’ll have a “minor-third”. This is a whole-step down from the fourth and is a Maj7 chord.

The third degree note gives us the quality of a chord or scale, which means that it tells us if it is major or minor. Knowing what the third or minor-third is helps us to confirm the tonic, key, and other relative chords.

Putting the Pieces Together

Even if we only know three notes, we can still figure out the rest of the song. With D, B, G as our notes and G ending the verse we can define three things: G is the tonic, B is the major-third, and D is the fifth.

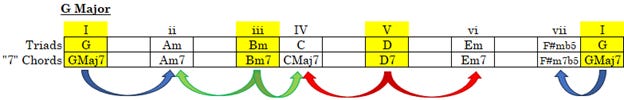

From there we can test this out by playing chords that are next to what we know. In the chart above G, Bm, and D are our known chords. Next to each of these known chords is another chord to try. This also gives us notes to play to test against the melody.

Remember how the verse ends with “won’t back down” sung with A, D, G? We’ll try out the chords that match. If Am7, D7, and GMaj7 work with the song then we can try out the other notes and chords to help confirm that we are in G Major.

From there we just need to work out the main melodies. Using the fifth degree as a strong pivot point, we can find that part of the verse melody uses the notes B, D, E, D, B with “No, I’ll stand my ground”. This is followed with G, A, B, G, G for “Won’t be turned a-round”. Now we have chord and a melody and can figure out the rest of the song from just a few repetitions of the verse.

This is a basic technique to help you start ear training so you can better understand the sounds notes make against a tonic. Keep singing “Oh-Yeah” and “Ah-Men” with your perfect and plagal cadences. Then you can listen for the quality of the major and minor thirds.

When you’ve figured out a song, try challenging yourself and play it in another key. The notes will be different, but the cadences and relationships to the tonic will remain the same. Keep in mind that ear training can be difficult, so focus on the fourth and fifth as the starting point for learning songs.

Thanks for reading and have a good one.

This really makes it crystal clear. Hearing the tonic and then orienting everything aurally in relation to that. The clever bit is knowing where to listen for the root and at the end of it verses is a great clue. I just tested it out on a couple of Motown classics and it was close to instantaneous. Great work and much appreciated.

Jay this is so helpful! I’m a trombonist and (too) slowly learning my scales and chords so I can put them to good use in my playing. Your explanations are crystal clear, but even with that it’ll take me some time to apply these fundamentals easily. Thanks for your help. I will subscribe when I can.