Ionian: The Resolution System

How to use the Ionian mode to your advantage for guaranteed strength in your resolutions or avoid resolving until you are ready.

The Power of Do – Re – Mi – Fa - So – La – Ti – Do

Ionian is a mode we all know well even if we’ve never heard of it. If you ask anyone to sing, “Do – Re – Mi – Fa – So – La – Ti – Do” with you, then there is a great likelihood that they will be able to sing those notes with you perfectly without rehearsing. We’ve heard this sung all our lives from kid’s songs to musicals. What many people don’t realize is that this is the Ionian mode. There are many reasons why it is easy to sing, but I believe that the best reason is due to its usefulness. Ionian spaces out the notes in a series of intervals that helps it to resolve almost perfectly. I say “almost” because there are ways to resolve strongly in any mode or scale. Ionian just offers a very straightforward method of gaining resolution.

Because of this, we may find ourselves playing another mode to purposefully avoid Ionian, yet we end up resolving to a final chord that is Ionian. An example of this is to play A Aeolian (or A Natural Minor) and play a progression of Am, F, G, Am and it works great. Then we try to finish our movement with something strong and we can even hear the final chord in our minds from of practice. So, we play Am, F, and G, but then we play C. That would be the Ionian chord creeping in and taking over with its strong resolution. Yes, we could have gone to Am again, but our mind’s ear hears that resolution coming and can draw us into Ionian like a moth to a flame.

Ionian And Its Alias

It’s difficult, if not impossible, to talk about Ionian without talking about the parent scale which is Melodic Major Scale. If we play Melodic Major as it is, then we have the Ionian mode. This scale is more commonly referred to as THE Major Scale. There are other major scales out there like Harmonic Major, but Melodic Major is what all other scales and modes are compared to. Just keep in mind that Melodic Major is THE Major Scale, and that Ionian matches it exactly. When we start talking about modes we mean the subsets of scales that we can create using a parent scale.

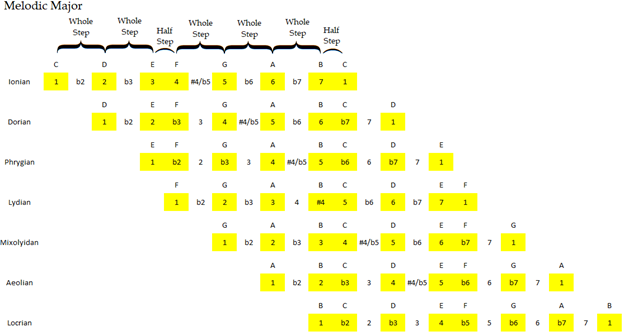

Melodic Major is constructed using a series of whole steps and half-steps between notes. If you are unfamiliar with step intervals, then think of playing one note and then the next note higher. That is a half-step, and two consecutive half-steps make a whole step. Melodic Major is constructed using two individual whole steps, one half-step, three individual whole steps, and another half- step. Melodic Major’s first mode is Ionian because it begins on the first degree of Melodic Major. If we started on the second degree note, then we would be using the Dorian mode. There are a total of seven modes for the Melodic Major Scale, which are shown above using C as the note for the first-degree position.

The chart above shows the degree numbers used for each mode. Ionian is the only mode that has no sharps or flats, which is why all other scales and modes can be compared to it easily. If we play a different parent scale like Harmonic Major, then we have the same degrees as Melodic Major but with a flattened sixth degree. This means that Harmonic Major’s first mode is Ionian b6. There are plenty of exotic scales out there and their first mode can always be compared to Ionian as starting point.

The Structure of Ionian

Each degree has a name and a function. I wrote about the function of these degrees in another post, so I’ll keep things brief. Degrees 1 through 7 are the Tonic, Super Tonic, Mediant, Sub-Dominant, Dominant, Sub-Mediant, and Leading Tone.

We can describe each of the seven degrees as numbers as well, which can help us to find target notes based on functions. If we want to end an Ionian melody on one of the notes of the matching major chord, then we can use degrees 1, 3, or 5 as each degree is part of a major chord. Ionian also gives us a Maj7 chord, so we can end on degrees 1, 3, 5, or 7 for that chord.

We can also play suspended chords by playing a chord with degrees 1, 5, and then either 2 or 4. This causes the chord to “suspend” the third degree down or up to degrees 2 or 4. We can also play a melody and end on degrees 2 or 4 to “suspend” the melody. Then we can play another melody to resolve to degrees 1, 3, 5, or 7 as needed.

This leaves degree 6, which is the Sub-Mediant. This is also the degree that starts our relative minor. By ending a melody on degree 6 we make part of our song feel minor or feel like it needs to move on toward tonic.

There are many variations on what you can do with Ionian melodies and chords. What I suggest you do is play something, anything, and end on a specific degree like 2. Then try another melody and end on the same degree. This way you can hear/feel what each note does for you. Are you ending on 1, 3, 5, or 7? Then you are ending in part of your Maj7 chord. Did you try 2 or 4? Then you are suspending, and your following melody will be stronger if you use degree 3 because it resolves a suspending melody into a major chord melody. Did you go bold and end on 6? Then you made the melody feel minor and playing another melodic line ending on degree 1 will bring the feeling back into Ionian.

Ionian Drives Toward The Tonic

While we can compare any scale or mode to Ionian, we do not call the parent scale Ionian. A parent scale is a series of intervals that we create modes from by using any of a scale’s degrees as a starting point or tonic note. Each mode has a Tonic note within itself, which would be the yellow ones in the above chart. The true tonic can only be one of the notes from the parent scale. If my song uses the C Major Scale as shown above and it ends on a CMaj7, then C is my tonic note because it is what I resolve towards. The other notes are tonic within their own melodies and chords that fit those modes, but all the chords and melodies eventually move toward my true tonic of C.

The term Tonic can be a bit confusing because of the way resolution works. Below is a short audio clip I put together to highlight Tonic functionality. I start it off with an A Minor chord in first inversion. This sounds fancy, but it’s just an Am with the second note of the chord in the bass. This makes it feel like a chord rooted in C, which will be our True Tonic or Absolute Tonic. The chords after that are F major, G major, and C major. Each chord has a little melody with it that ends on A, F, and G which are also notated in red. The final Tonic note of C is also pointed out in red. Listen to it and notice how each red note is where part of this piece resolves to. The final resolution is C, which can be felt as our Absolute Tonic note. Keep in mind that I chose these chords because they fit the Ionian mode and will give you a strong Ionian resolution.

Strong Resolution Through Cadences

Try playing an F major chord followed by moving down to a C major chord. Then play a G major chord followed by moving down to a C major chord. F is the fourth-degree chord, G is the fifth-degree chord, and C is the first-degree chord. By playing F to C, we have a 4 to 1 relationship. The same goes with G to C in a 5 to 1 relationship. Each movement has its own feel. If I have part of a song that I am writing that ends in G major followed by C major, then I can move up or down to C major and using either combination of feeling.

This may sound a bit convoluted, but it works. When we play a song and end a movement, we are using a cadence. Think of a cadence as how you end part of a song. This can be any combination of two or more chords. For this example, we’ll use the Plagal Cadence (the 4 to 1 relationship using F to C) and the Perfect Cadence (the 5 to 1 relationship using G to C). The Perfect Cadence does have another name which is the Authentic Cadence and both names are used depending on if you move up or down to the next chord. For now, let’s just stick with the Perfect Cadence for naming convention and focus on the result.

The Plagal Cadence is the “ah-men” church cadence. Think of a church song and at the end it goes “ah” with F major and then “men” with C major. The Perfect Cadence is the “oh yeah” cadence. Think of a 50s or 60s rock song that ends in “Ooooh” with G major and then “Yeeeeah” on C major. When we use these cadences, we typically move down to the second chord. However, if we move up to the second chord, we are using a different interval which gives us a different feeling. If I want to end part of a song with G major followed by C major, then I would have a Perfect Cadence, but if I move up to C I am using a Perfect Fourth interval. This causes the movement to feel somewhat Plagal. The same happens if I play F major and move up to C Major. This is a Plagal Cadence but borrows some of that “oh yeah” flair and makes it feel like a Perfect Cadence. Try playing around with three to five chords and use either F to C or G to C in the end. Listen to how the mood changes SLIGHTLY depending on if you move up or down between the last two chords.

Progression Uses

The chords of Ionian are Maj7, m7, m7, Maj7, Dom7, m7, m7b5 no matter what key you are in. Since we are using the C Major Scale for these examples, we have no sharps or flats and use the chords CMaj7, Dm7, Em7, FMaj7, G7, Am7, Bm7b5. Each chord begins on a degree of Ionian so we can also name these chords by degree numbers using roman numerals, which are IMaj7, iim7, iiim7, IVMaj7, V7, vim7, and viim7b5.

This becomes incredibly helpful when we start talking about progressions. If someone asked me to play a “6, 2, 5, 1” then I know to play chords and melodies belonging to vi, ii, V, and I. The only thing to ask is what key do they want me to use? The keynote is where Ionian starts. If I was asked to use G as the key, then a vi, ii, V, I could be Em7, Am, G7, C. I can use any chords that are rooted in E, A, G, and C as long as they use the notes found in the key of G, which are G, A, B, C, D, E, and F#.

I cannot use a progression like Em7, A7, G7, C because my third chord is a minor seventh and not a dominant seventh chord. Now there are ways to use chords that are not diatonic (diatonic means it fits the scale or mode). We’ll stick to diatonic chords only so that we only use progressions that fit the Ionian mode.

The way we construct a progression is normally by going from a Tonic chord, to a Pre-Dominant chord, and then a Dominant chord that resolves back to a Tonic chord.

Tonic chords are chords that do not have the fourth degree note in it. In C Ionian we have CMaj7, Em7, and Am7 as Tonic chords because they do not contain the note F. Pre-Dominant chords contain the fourth degree, but not the seventh-degree notes. Dm7 and FMaj7 both contain the note F, but not the note B. Dominant chords contain the fourth- and seventh-degree notes. G7 and Bm7b5 both contain the notes F and B. You can play G major without the note F, but it is implied as being a natural part of the way that chord is built beyond its basic triad form.

Below is a road map for how this all works. Keep in mind that you can return to a Tonic chord at any time and that you can skip the Pre-Dominant Chords as well. Another thing you can do is play any number of Tonic chords, any number of Pre-Dominant Chords, and then any number of Dominant chords that resolve back to a Tonic. What does not happen is going from Dominant to Pre-Dominant. Keep in mind that this is the standard way of creating a chord progression. There are plenty of ways to break the rules. Think of Music Theory as a rule book that is meant to be broken if it sounds good to you.

Ionian Examples:

vi, ii, V, I Am7, Dm7, G7, C

iii, ii, IV, I Em, Dm7, F, CMaj7

VI, V, iii, vi, ii, V, I F, G, Em, Am7, Dm, G7, C

iii, vi, IV, ii, V, vii, I Em7, Am, FMaj7, Dm, G7, CMaj7

Escaping Ionian’s Pull

Ionian’s ability to resolve so strongly is as much a great tool for composers as it is a weakness. If I was trying to play something in A Aeolian (or A Natural Minor) I could easily find myself ending part of the song on C. A Aeolian is one of the relative modes of C Ionian, which means that they have the exact same notes in them. I could try to play progression like Am7, F, G7 and then one more chord to end the progression. If I play Am, then the progression would feel Aeolian. But if I play C, then my progression feels Ionian. Going to C gives me a stronger resolution, so it sounds great. The problem is that I don’t want to play Ionian and I still want everything to sound fantastic.

That’s where mood comes in. Each mode has its own mood. Ionian is happy, bright, and full of resolution. The other modes have their own emotions tied to them along with their own versions of incomplete resolution. A great incomplete resolution would be for a sad song that trails off with a feeling of despair. That’s not what Ionian offers us.

The real issue is that Ionian is always available. It will exist relative to any other mode or scale that you use and resolves so well that you may find yourself using it unintentionally. The audio clip below will use Em7 and FMaj7 back and forth with a melody followed by Bm7b5. I’ll then play Em7 to end this piece with a darker Phrygian feel to it. Then I’ll play the exact same thing but end on CMaj7 to make it sound Ionian. Ending the first part with Em7 helps us to not use the classic Ionian resolution until we are ready to by playing CMaj7. This is that double-edged sword that Ionian gives you: a strong resolution and only a strong resolution.