Hidden Patterns in the Major Scale

Five simple patterns for any musician.

Pattern Recognition

One major aspect that's makes us human is our ability to find patterns. In music we hear patterns that we can describe as style or genre. We know the difference between a rock song and a country song based on the repetitious elements.

If you were to ask a friend to hum a style of song, they would hum a pattern that they've already heard. Rock, country, and pop are all broad styles that most people should be able to hum for a brief moment. But what would happen if you asked them to hum a feeling? Try humming happy and sad. Now try humming anxious or confident. Feelings can be harder to describe until we start exploring scales and modes. By using modal descriptions, a musician can begin to describe many complex emotions.

Today we'll look at patterns within the major and minor modes of the Major Scale. As we begin to see the same patterns occurring, we will gain the ability to use those patterns to draw out emotions. If you are not familiar with modes, then please check out my archives section. There's plenty of information on each mode that we will discuss along with many related articles.

The Setup

Last week we worked on the three major modes and how to treat them as one system. To see the patterns in the Major Scale we'll start with the major and minor modes in a specific order.

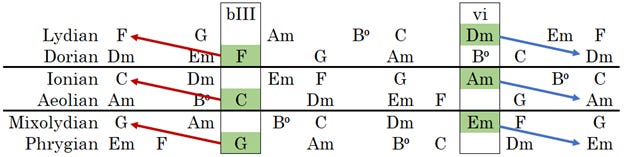

Above we have the modes in order from sharpest to flattest. At the top we have the major modes and at the bottom we have the minor modes. The first thing to note is the pairing of major with minor modes.

Ionian and Aeolian are relative pairs in that we can play C Ionian and A Aeolian at the same time because they share the same notes and Aeolian starts on the sixth degree of Ionian. In the chart above they are the middle modes of major and minor.

Lydian and Dorian are also a pair. If you play F Lydian and move to the sixth degree, you will be at the note D. This starts the D Dorian mode. Again, we have a major and minor pair with the same intervallic spacing from the Tonic to the sixth degree. Mixolydian and Phrygian follow this rule as well. G Mixolydian's sixth degree is E, which starts E Phrygian.

If we are playing any of the minor modes and go to the minor-third (bIII), then we will be at the first note of the paired major mode. For example, A Aeolian's minor-third is C, which begins the C Ionian mode.

Anchor Points

Now that we have the modes in order and in pairs, we can add in the first layer of patterns. Below we have all the major chords in the major modes highlighted in blue. All the minor chords in the minor modes are highlighted in red.

Do you see the first pattern? The same chord positions/degrees that are blue in the top half are red in the bottom half. Lydian and Dorian’s highlighted chords are 1, 2, and 5. Ionian and Aeolian’s highlighted chords are 1, 4, and 5. Mixolydian and Phrygian’s highlighted chords are 1, 4, and b7. If you were to play only three major or minor chords from any one mode, then you would give away the sound of that mode to your listener.

For example, playing the major chords G, A, D would sound Lydian because they would be the I, II, and V chords in G Lydian based on position/degree. What makes knowing this pattern extra helpful is that by playing G, A, D we end up playing all the notes in G Lydian: G-A-B-C#-D-E-F#. G major is G-B-D, A major is A-C#-E, and D major is D-F#-A.

I know we are focusing on chords but imagine a trumpet player using these patterns. The trumpet can only sound one note at a time. Instead of playing chords of multiple notes the trumpet can be played with arpeggios, which allows chords to be described in melodies. Playing a G major, A major, and D major melodic line will sound like a G Lydian melody. Knowing that you can play major melodies over the I, II, and V chords and produce a Lydian sound allows a musician to specify the feeling of a mode from just a few degree positions.

Grouped Chords

The next pattern is found with grouped chords. These are similar chords that neighbor each other, so in the major modes we are focusing on major chords. The minor modes therefore use minor chords as their neighboring groups. So how does this help us?

Imagine playing in G Mixolydian and its paired mode of E Phrygian. In G Mixolydian the two neighboring major chords are F major and G major. In E Phrygian the neighboring minor chords are Dm and Em. What’s helpful with this is that we can know that in both modes the chords match the mode (major with major and minor with minor) and use degrees b7 and 1. Since each of the six modes listed only has two major chords neighboring, and two minor chords neighboring, we can give away the sound of the mode based on position yet again.

Notice how as we move down through the modes the groups move to the right. Lydian and Dorian’s groups are on degrees 1 and 2, while Mixolydian and Phrygian use degrees b7 and 1. Ionian and Aeolian are the middle modes and have their group in the middle with degrees IV and V.

Another thing that’s great about these groups is that they are separated by the third and sixth degrees (b3, 3, b6, and 6). This creates a nice separation between where groups can exist. We do not have groups on the third and sixth degrees because those are our “green” positions where the relative pairs begin.

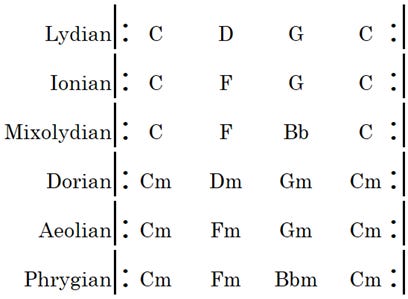

The Perfects

There’s one more commonality that can help us to locate the major chords in major modes and the minor chords in minor modes. In Ionian and Aeolian, we have both the perfect fourth and perfect fifth (IV and V) as chords. The “higher” paired modes of Lydian and Dorian only have one perfect chord, which is the “higher” of the two perfect chords (the V & v chords). Mixolydian and Phrygian are at the “lower” end and get the “lower” of the perfect chords (the IV & iv chords). Now to use it. Try playing the follow six sets of chords as you like and listen to the flavor of sounds produced. This will give you a good sense of how each mode sounds within specifically a major or minor context.

What to Practice

We’ve covered a lot here, so I want to make practice simple for this concept. No matter what your level of playing is, try to focus on the major chords in major modes and minor chords in minor modes. Remember, you don’t need to play chords at all. Arpeggios work just as well. Try playing a mixture of chords, arpeggios, and melodies over the major chords of the major modes. Then do the same thing with the minor chords of the minor modes. This works in any key, so listen for the sound of the mode no matter what notes you are playing. Ultimately this is an ear training exercise because it will allow you to pick out major and minor chords along with the position/degree that they are from.