Getting Back to Basics for Beginners and Pros

A simple way to start learning music that is also a fun challenge.

Where Do I Begin?

The best tool to start learning music with is the C Major Scale. Let’s jump right into it on the piano and guitar. Below we have the notes of the C Major Scale for one octave. An Octave is the distance from one note to another note that uses the same name. In this case we are using all of the natural notes from C to C. A natural note is a note that is neither sharp nor flat. It is just the letter.

A nice feature of the Major Scale in any key is that we can describe this scale in natural degrees. A degree is a type of number that describes the relationship between notes from the first note used. In this example C is our first degree, so it is given a 1 to denote this. Yes, each note after that is 2 through 7, but there are two features that I want to point out.

The distance from one note to the very next note is a half-step. When looking at the piano, degrees 3 and 4 are a half-step apart. So are degrees 7 and 1. Every other interval between notes uses a whole step. In other words, a black key is skipped over from degrees 1 to 2, 2 to 3, 4 to 5, 5 to 6, and 6 to 7. To memorize this, many people use “whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half” as a way to count out the steps of the Major Scale. But there are two easier ways.

The first is to use “Two and a half. Three and a half.” This is a short way of saying that there are two whole steps to cover degrees 1, 2, and 3, a half step to go from 3 to 4, three whole steps to cover degrees 4, 5, 6 and 7, and another half step to go from 7 back to 1.

Another way of simplifying this is to simply know that there is a half step from degree 3 to 4 and a second half-step from degree 7 to 1. This means that all other steps are whole. Now there is no need to count steps. You are either working with 3 to 4 , 7 to 1, or some other degree pair which will only use whole steps.

Below we have the same idea of a single octave on the guitar. This chart puts the frets that our fingers touch as vertical columns. The horizontal lines are the string and are numbered 1 through 6 from top to bottom. This order from the strings is also the highest tones on string 1 down to the lower tones on string 6.

Keeping the half-steps in mind, we can start at the lower toned C on the fifth fret of the third string and imagine that a half-step to the left is the 7th degree note of B. A whole step to the left of E on the 2nd string would be the note D and a whole step to left of A on the 1st string would give us the note G.

Chords and Inversions

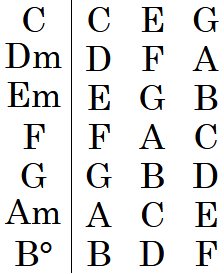

When we first learn chords we stick to three-note chords call triads. In the C Major Scale they are C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am, and B°. The three chords that are just letters are major chords. The three chords with an “m” next to them are minor chords. The last chord with the ° symbol is a diminished chord. The notes used in each chord are shown below.

Since we are sticking to one octave we will be using some inversions. Lets check out the the first three chords to see what an inversion is not before getting into inversions. Below are the chords C, Dm, and Em. Each chord is within our one octave range and can be thought of as using every other note in the C Major Scale. These chords are not inversions because the root note, or note that we build the chord from, is the lowest tone.

Next up is the chord F. On the piano we can play this with the notes F A C or the notes C F A. On Guitar we only have C F A as an option with the single octave that we are using. When we play F as F A C it is not an inversion because the root note F is the lowest tone. The chord that uses C F A is still the chord F, but it is an inversion because one of the other notes is the lowest tone. If we placed A as the lowest tone, the F chord of A F C would be in “first inversion” because the next available note is in the bass end of the chord. Since we are using C F A as our F chord it is in “second inversion” because C is the second note in the chord after F. This means that the order of notes isn’t always important. What is important is that we use each note of a chord in some way.

The rest of the chord are constructed in inversions. G is in second inversion because out of the notes G B D, the second note after G is in the bass. Am can be played as C E A or E A C on the piano, by our single octave limits the guitar to C E A. B° is in first inversion as D F B. We also have a second C chord that is played in first inversion as E G C.

The Last Step

Now that we have some chords that we can play, we should add in Functional Harmony. I have plenty of articles that focus on this topic, so to keep it simple we can think of it like this. The 1st, 3rd, and 6th chords (C, Em, and Am) all have low tension. They are relaxed and fit in. C really relaxes things as it is the first degree chord and is a great way to end parts of a song as the final statement or punctuation mark of what you want to say musically.

The 2nd and 4th chords (Dm and F) have some tension. They get us moving. We are not totally relaxed with these two chords, but we we’re not under pressure with a lot of tension. These chords move us between low and high tension and thus create movement between the feeling of relaxation and intensity.

This leave the 5th and 7th chords (G and B°) which have higher tension. The tension these chords provide act as a call for resolve. We can use the tense chords to make a statement and then either resolve it quickly by going to a relaxed chord or using a lighter tension chord before resolving. Either way, the first degree chord is always a great way to resolve tension.

High Tension / Calls for Resolve: G and B°.

Moderate Tension / Creates Movement: Dm and F.

Low Tension / At Rest: Em and Am.

Low Tension / Resolves: C.

The Challenge

With our scale and chords in hand we can start to play music. Try a progression like Am, Dm, G, C. You can play each chord as long or as little as you like. The point is that we start off relaxed with Am, then we add some tension with movement in the Dm chord, the G chord ramps up the tension, and C resolves the movement. You can even play C and Dm back and forth for a relaxed feel, some movement, and back to relaxation.

You can even play a little melody with just single notes. Pay attention to the last note you use as this can draw out the same tension that the chord gave. If you end a melody on D or F, then you end with some lingering movement. Ending on G or B wants you to add one more short melody that ends on C to resolve G or B. Ending a melody on E or A can relax the melody, but not fully resolve it with the first degree note of C.

You can even play melodies based on chord tones. A melody that uses D F A a little followed by the notes G B D that soon ends on the note C by itself is like playing Dm, G, and then C. We have movement with the notes D F A, tension is added with a call for resolve with G B D, and then ends the melody on the note C to resolve it. You will hear how powerful this is the more you use these ideas and listen for the tension.

Now for the challenge. As you learn about other chords in the C Major Scale like CMaj7, Dm7, Em7, FMaj7, G7, Am7, and Bm7(b5) you will be using four-note chords. These chords still use every other note, so CMaj7 is C E G B. It isn’t possible to play four notes on three guitar strings, but you can play a melody with four notes. Even chords like G7sus4 played with G C D F are fair game because they use notes that belong to the C Major Scale.

The challenge to beginners is to learn the seven triads that we covered and the scale as degrees 1 through 7 with the half-steps accounted for. This may take some time, but once you are confident that you have this down you can then work in four-note chord and other chords to help expand on what is possible.

The challenge for intermediate and pro players is to stick to one ocatve and use only those notes. At this point all thirteen notes are fair game from C to C. Use modes, other parent scales, and even complex melodic line from blues and beebop. By restricting ourselves to one full octave we are forced to use specific notes once except for the tonic which encompasses our octave. By have limits we have to think more about inversions and placement of melodic lines.

Thanks for reading. I hope this jump starts you into a practice routine that you can use to explore the Major Scale more efficiently. Have fun and keep on jamming.