Degrees of Musical Notes

Wrapping our heads around degrees of scales, modes, chords, and so on.

A Footnote to Modal Thinking

My last article explored the differences between scales and modes. But I avoided talking about “degrees of degrees” because I want to focus on the idea that each mode only fits within the Major Scale in their own specific way. Before I move on to more modal topics, I want to take the time to talk about “degrees of degrees”.

So what is a degree? Its simply a numbered location within a scale. When we think of the Major Scale we have seven degrees, so there are seven locations all in a line and are conveniently numbered one through seven. The trick to it all is that every location is where a note exists and they are all given a little space between each other… except for two spots. From degree 3 to degree 4 there is no space. The same goes for degree 7 next to the another occurrence of degree 1.

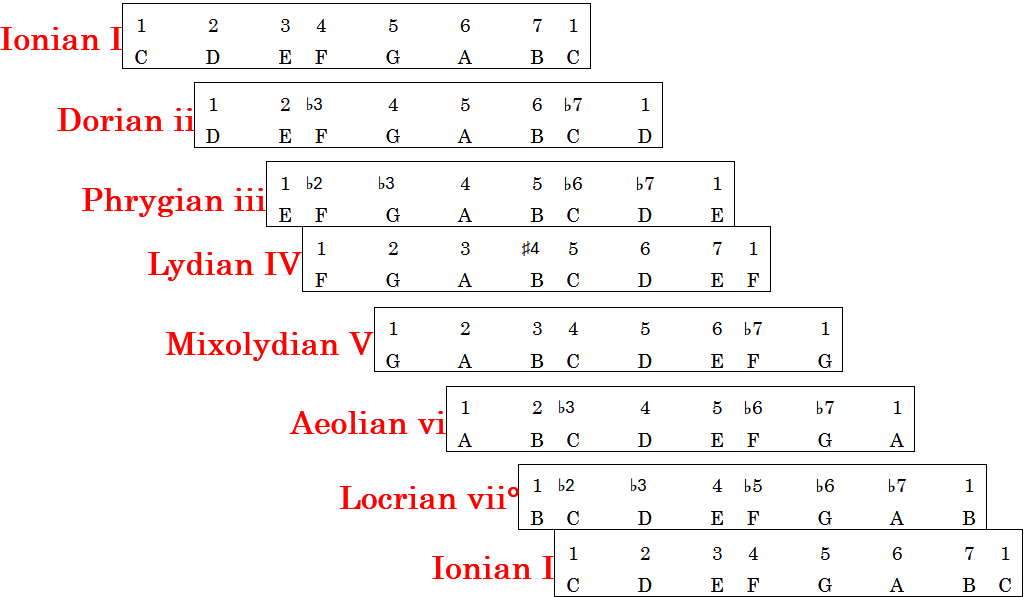

While the chart above describes the Major Scale as these seven specific locations. It fails to explain a degree of a degree. To start, we should think of the Major Scale with the roman numerals in the next chart.

Each of these seven notes has a specific function within the scale. Here’s a brief rundown of each one, with some skipping around so that the rest of the article makes sense.

I is the Tonic. It is what all other degrees are relative to. The Tonic note provides a frequency, or sound wave, that allows our brains to say, “Yes. Got it. THAT wavelength is ‘one wavelength’. Thanks for making that clear.” All other degree notes are a wavelength that is a fraction of the Tonic, which allows our brains to compare and contrast wavelengths.

IV is the Sub-Dominant and vii° is the Leading Tone. The Sub-Dominant creates a sense of movement. The sound is not settled and relaxed, but it is not tense. It is a nice in-between place of general “movement”. The Leading Tone is a somewhat tense note that “points” to the Tonic, which happens to be the next note higher. When degrees IV and vii° are played together, they create a space between notes known as an interval, which is called a Tri-Tone. Only degrees IV and vii° can do this. When the Tri-Tone is activated a sense of “movement" combined with “pointing to the Tonic” results in a “push toward the Tonic.”

V is the Dominant. This note has a frequency that works so well with the Tonic’s frequency that it helps drive back to the Tonic with ease AND helps the Tonic gain strength by pairing with it in harmonies. Chords that start with degree V can lead into using a Tri-Tone. Overall, the Dominant is a note that strongly drives to the Tonic by connecting with it.

vi is the Sub-Mediant, but more importantly it is the beginning note of the Natural Minor Scale. This allows degree vi to be used as a “Minor Tonic”. Degrees IV and vii° can therefore “push toward the Tonic” that can be the Major Tonic of degree I or the Minor Tonic of degree vi.

ii is the Super Tonic. There is nothing super about it as the word “super” simply means “above”, so it is the note above the Tonic. This degree is close to the Tonic, so the note alone can easily move down to the Tonic position. Degree ii’s main chord uses the IV note, so it can also have a sense of movement. Degree ii is also the fifth degree of degree V. So you can think of it as a “v of V”. That’s like saying degree ii is the “minor dominant OF the dominant”. Hang on to that idea, because that’s where we are heading today.

iii is the Mediant. Its a half-way point. Its not near the Tonic or the Dominant, and it has no tension. It doesn’t really combine with anything in the way that degrees IV and vii° can combine to create a Tri-Tone. Though degree iii IS the note that makes the Major Scale “Major”. Without the distance from I to iii, we would have no “Major” sound. If we flattened the Mediant to be a ♭III, it would become a Chromatic-Mediant and create a “Minor” sound. The Natural Minor Scale HAS a ♭III and gets the “Minor” sound from that note. So whenever you see a chord like iii, you know its part of the Major Scale. Another other form like III7 is coming from somewhere else in the musical world.

Modal Degrees of Scale Degrees

OK. Here we go!

Imagine those seven degrees with the roman numerals. Make them big and bold! If the notes we use in our Major Scale are C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. Then C is degree I, D is degree ii, and so on. Take a moment and imagine each lettered note as OWNING THE RESPONSIBILITY of each function I mentioned and proudly wears a roman numeral badge on it. Silly, I know. But that is the level of distinction we need to start with.

Once you have that down, think of the note G. It is the fifth note after C, so G IS THE FIFTH OF C. That also means that G is the “5th of I”. Now consider the notes D and G. If D is degree ii and G is the 4th degree of D. Starting to get it? Each note carries the responsibility of functioning within a scale, but it also acts as a degree of another degree. All combinations of two notes work this way.

So D is degree ii and “G is the 4th of D”. What about D and G when we use G as degree V? Then D is a degree of G, which would make “D the 5th of G”. This can be hard to understand in text alone, so check out the next chart.

Let’s look a D and G again. The Dorian mode starts on the second degree of the Major Scale. Within “D Dorian”, the note G is D’s 4th degree. So if we play a chord like Dsus4 with the notes D-G-A and follow it with a C major chord using the notes C-E-G, we end on the Tonic and before that we use the note G as a way to connect to the Tonic using G for its Dominant Function. When the chord Dsus4 was heard, the note G gave the ILLUSION that it was the “4th of D” when it was actually degree V from the scale and therefore was a Dominant note.

If that still isn’t clear, then try this.

Notes that are scale degrees always retain their scale function.

Notes used as the degree of a scale degree create sub-functions.

So let’s try it again in a simpler fashion.

Start with a Tonic chord of C major, a.k.a. C. Again, this uses the notes C-E-G. Now play a Csus4 with the notes, C-F-G. Did you feel the movement that the Sub-Dominant created? Now try a C△, a.k.a. C major seven. The notes for this chord are C-E-G-B. B is the Leading Tone and is pointing to C. Play C△ and then a four note version of C major with C-E-G-C. Did you feel how the Leading Tone note of B pointed you to C? Now try a funky chord like C△sus4 as C-F-G-B and follow that up with the four note chord of C major with C-E-G-C. The combination of F and B, or IV and vii°, created a Tri-Tone that was easily resolved with a Tonic chord.

Now let’s ramp it up again.

This time play Dm (D-F-A) to C (C-E-G). Nice and simple with only a touch of movement from the note F as the Sub-Dominant in the scale. Now play Dm6 (D-F-B) to C (C-E-G). Yes, F is the ♭3rd of D and B is the 6th of D according to the Dorian section of the above chart. BUT… F and B are degrees IV and vii° in the C Major Scale. So…

F and B are scale degrees that retained their scale function and drove us to C as the Tonic.

And…

F and B were used as the degrees of the note D, which created sub-functions to form the chord Dm6.

Explore the chart above and use each note as degrees of a scale that have function. No matter what chord you use, these notes will not lose that functionality. This is also true for melodies. Experiment with each “scale function” and you’ll begin to hear those functions no matter what chord or melody you use. You can also listen to songs and try to pick out the degrees and hear the functions within them. Take your time learning degree functionality because it is one of the aspects of musical exploration that makes all of music so very interesting.