Cowboy Chords for Any Instrument

Campfire harmonies are for more than just guitar.

What is a Cowboy Chord?

Whenever we think of someone strumming a guitar by a campfire, our mind’s ear can imagine a relaxing tune. Cowboy chords are named so because they are easy to strum and are some of the first chords most guitarists learn. Songs that fit the “campfire sing-a-long” genre are often played on the guitar and use these simple chords. However, these chords are not just for one instrument and they are useful in many genres.

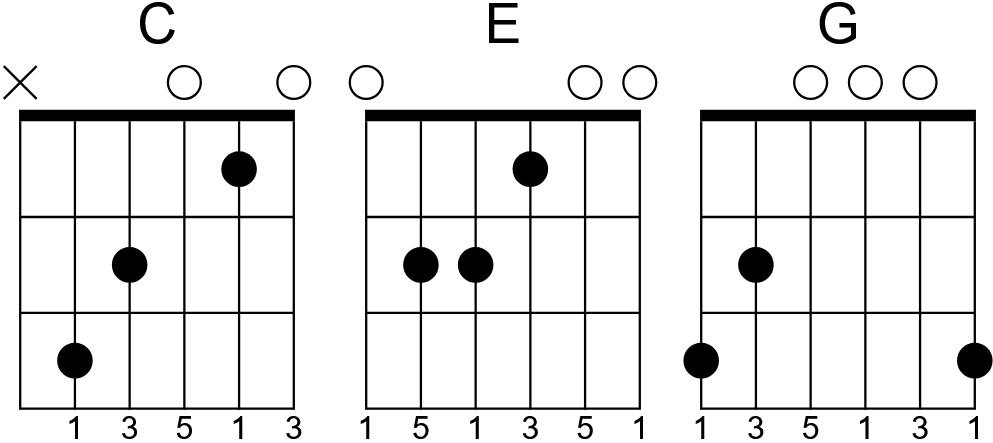

The details of a cowboy chord are revealed when we look at how they are voiced, which a “voicing” is a way for saying “how a set of notes is harmonized together”. Below are three chords: C Major, E Major, and G Major. If you are not familiar with this type of chart, think of the thick line at the top as the end of the fret board by the head-stock of a guitar. The six vertical lines represent the six strings. The horizontal spaces are the fret spaces. An “X” means to not play that string and an “O” means to leave the string open and play it as it is.

I’ve added numbers at the bottom of each chart. These numbers are the degrees for the notes in each chord. Notice how they only use the numbers 1, 3, and 5. In a seven note scale, like the Major Scale, the number 1 is the starting note. In a chord, this is also called the “root note” as it is like an anchor point to build from. The “third” and “fifth” are specific notes from the Major Scale. These are of course the third and fifth notes of that scale, but more importantly they represent functions.

The fifth degree is also called a “perfect fifth” and works perfectly with the root note. In fact, the fifth works so well that “power chords” used in rock and metal only consist of these two notes. In Jazz the fifth is the first note to exclude because it just works with the root and doesn’t add any “color” or “feeling”.

The third is the “quality note”. If the number used is a 3, then the chord is a major chord. A ♭3 is just a half-step down in pitch from 3, but this is what creates a minor chord. Just like the number 5 being called a “perfect fifth”, 3 and ♭3 are the “major third” and “minor third”.

OK. Now that we have a general idea of how these three numbered notes work, we can review the chords.

Breaking it Down

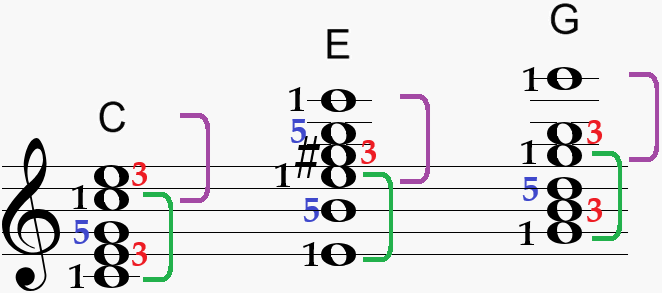

Below are the same three chords with some numbers and brackets. Here’s how this chart works. “1” is the root note and is black. “5” is the perfect fifth and is blue. “3” is the “major third” or “quality note” and is red. The first octave is grouped by a green bracket and the second octave is grouped by a purple bracket. An octave is the distance from one note to the next note, so the first octave of a C Major chord starts and ends with the notes C and C. The second octave starts on the second C note and continues to the third C note. The same goes for E to E to E in the E Major chord. I think you get the idea for the G Major Chord.

The commonality between these chords is not obvious, but there is one. Each of these chords has three rules that are used to construct them.

The first octave contains a power chord, which uses the 1st and 5th degree notes with an additional 1st degree note to encapsulate the first octave.

The second octave contains a 3rd degree note.

Any additional notes must consist of the 1st, 3rd, or 5th degree notes.

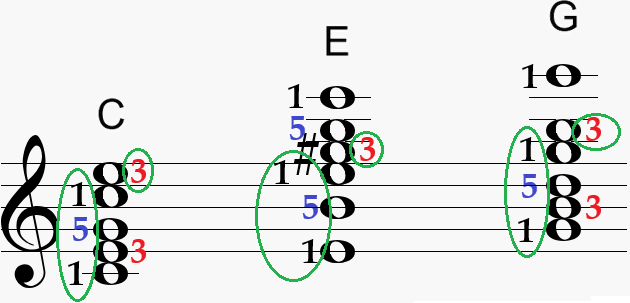

This combination might seem like it’s just a set of 1s, 3s, and 5s, but think about it. A cowboy chord is a power chord of 1-5-1 with the third above it. The additional notes are more or less duplicates or options. Out of these optional notes, there are only three possible additions: a third in the first octave, a fifth in the second octave, and a root starting the third octave. Another way to view these chords is show below. The mandatory notes are circled in green. Everything else is optional.

Chord Tones VS Node Tones

So what can we do with the cowboy chord sound? Well keep those mandatory notes in mind. A good formula for them is 1-5-1-3 because it describes the degrees that we have to use. When we play a chord or arpeggio, which is a chord broken up into one note at a time, we use “chord tones”. These are notes belonging to a chord. In this case we want that three note power chord with a third above it, so 1-5-1-3.

“Non-chord tones” are notes that are not used in the chord, but still exist and are optional. In the cowboy chord we have notes that do belong to the chord, but are not mandatory. These can be thought of as “node tones”, which I literally just came up with to help describe this next concept. Each optional note in the cowboy chord can function as a “node” that we can connect to and from. Try playing a chord of 1-5-1-3 with a melody in the second octave. The melody should end on one of the optional notes and connect back to the cowboy chord. This way the chord is played with mandatory notes and then a melody ends by adding in an optional node note. If you want more of a cowboy chord sound, then have a melody start and end on one of the optional node notes.

You can also add another third degree note in the first octave. This is great for when the melody does not touch the third degree note in the second octave. Having two “thirds” in a chord can make it sound ambiguous. But here’s the kicker: a cowboy chord gets part of its sound from being ambiguous. That means that you can double up on thirds and have them in both octaves.

Another way to think of chord tones and node tones is as two sets of notes that you can anchor your melodies to. The 1-5-1-3 notes are your main anchors that hold the harmony and are played together. Adding in another 1st and or 5th degree in the second octave allows melodies to anchor to those higher pitched notes. Adding another third in the first octave creates that ambiguity, or allows the third in the second octave to have some reprieve and not be played for a moment simply for the sake of the melody.

Try this out yourself by (1) playing around with 1-5-1-3 in the form of chords and arpeggios. Then (2) touch on the additional first, third, and fifth degree notes that can be added to the chord. Now (3) explore melodies that start and/or stop on these additional notes.

You may be surprised how laid back the totality of the sound is when structuring melodies around a 1-5-1-3 format with optional 1st, 3rd, and 5th melodic nodes.

Nice post. The voicing sounds so natural because it mimics the overtone series. Amazing how playing these structures makes chord melodies on guitar sound sweet.