Little Moments Make Big Impacts

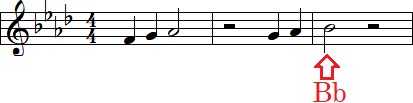

The best songs in the world have many qualities. A great chorus that a crowd can sing to, a slick drum groove, and great lyrics are just some of the aspects of popular music. One thing that helps drive the story telling of a song that is often overlooked is pre-dominance. In the movie "The Little Mermaid", Ariel gives up her voice by singing. The first notes sung are F, G, Ab followed by G, Ab, Bb. This may look like a simple ascending line in the key of F Minor, but it is a great set up for the rest of the scene.

The first three notes of F, G, and Ab are F Minor's scale degrees 1, 2, and b3. The next three notes of G, Ab, and Bb are degrees 2, b3, and 4. Then the singing starts at F again and begins to ascend higher through the scale.

Bb is the focal point that sets up the rest of the scene because it is the fourth degree of the scale. This degree is special because it helps to change tension. In this scene, Ariel sings up to the fourth degree and begins adding tension. Without Bb we would only have C as the next note, which is the fifth degree. C would ramp up the tension considerably because the fifth degree of a scale is “the dominant”. C literally dominates the tensions and pulls us back to the tonic note of F. The fourth degree is the “Sub-Dominant”, which means “below THE dominant”. Bb is our 4th degree note and it leads us to or from higher tensions.

To understand the sub-dominant better, try playing F, G, Ab and G, Ab, Bb along with Ariel. Next, play these six notes again, but change Bb to anything else in the scale: F, G, Ab, C, Db or Eb. None of the other six notes will move the tension the way Bb does. Now that we have a sense of how powerful the fourth degree note is, let's use it.

The Basics of Functional Harmony

When we play a scale, we typically use seven notes on western music. The most common scales are the Major Scale and Natural Minor Scale, which use degrees 1-2-3-4-5-6-7 and 1-2-b3-4-5-b6-b7. From these degree formulas the only difference is in the third, sixth, and seventh degrees. Both scales have chords that we build by starting with a note and then adding every other note. Check out the chart below to see how C Major and A Natural Minor are built.

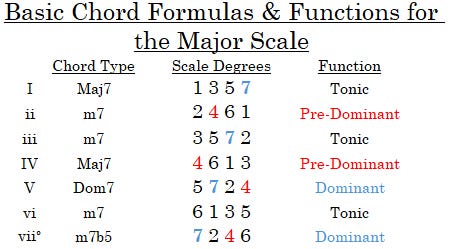

There are three general groups of tension when using chords. Tonic chords are "at rest" and do not have a 4th degree note from the scale. Dominant chords use the 4th and 7th degree scale notes and have a high amount of tension that calls for release. Pre-Dominant chords have a 4th degree note, but not a 7th degree note. These chords are what we are focusing on because they have some tension and act as bridge between Tonic and Dominant chords. We can start with any chord or note and progress to the Tonic, but rather than think of every note or chord we can focus on the three groups and use tension to write our songs.

The Power of Four

Considering the ways we construct Tonic, Pre-Dominant, and Dominant chords we only have a few combinations regardless of the degrees being sharp or flat. This is because the degree numbers from the parent scale are what matters most.

The above chart shows the basic formulas for functional harmony groups for any Major Scale. The first chord at the top is “THE Tonic” and is what everything moves toward to create “rest”. The three “tonic functioning” chords create “rest” but are not the end point of our song.

For example, a common vi-ii-V-I progression of Am, Dm, G, C moves toward C as the Tonic. We start with Am, which is a tonic functioning chord, but that only keeps is “at rest”. It is not “THE Tonic.” After starting at rest with Am, we increase the tension with Dm and ramp up the tension further with G. Looking at the chart below we have vi, ii, and V moving us through the tension groups. The last step is for G to move to our tonic of C. With this then tension is guided to a chord that functions “at rest” and is also our tonic, or tonal center. When we are moving tension, we are also moving to or from “THE Tonic”. In this case as vi-ii-V-I uses increasing tension that resolves to a completely “at rest” position.

Controlling Tension

The best part about using the fourth degree as a device to guide tension is that we don’t have to think in terms of chords. All we need to do is look for that one fourth degree note.

In C Major that note is F. In our vi-ii-V-I progression we have Dm as the ii chord. This chord uses the notes D, F, and A so it fits the pre-dominant format. Now what happens if we play a chord like Dsus2 or Dsus4 instead of Dm? Dsus2 is D-E-A and Dsus4 is D-G-A. Without the note F we have dropped the tension, so Dsus2 and Dsus4 both function as tonic chords.

We can also add tension to Dm by including the note B because it is the 7th degree note. By playing Dm6 as D-F-B we now have the 4th and 7th degree notes, so Dm6 is a dominant functioning chord. Now we can play chords with a root note of D, but we can also control the tension by being aware of the 4th degree.

The best way to get a solid grasp on this concept is to experiment with it yourself. You could play a progression in C Major that uses the chord Em and change it to see how it functions. A chord like Em b9 played as E-G-B-F would be a great example. The Em triad already has B, so the 7th degree is already there. However, Em is E-G-B. Without the note F, Em is a tonic functioning chord. By adding F as the b9 of E we are transported into a dominant function because we have the notes F and B. Keep in mind that F is the 4th degree of our scale AND is the b9 of the note E.

If you are playing with someone, then try splitting up the voices. A guitarist could strum an Em chord while a bass player plays an F note. Together an inversion of Em b9 is created. Inversions and multiple instruments are great ways to create broader sounds, but the 4th and 7th degrees still control the tension. Now start experimenting with the 4th degree note of a scale and see what kind of tension control you can do. Until next time.