Arriving Early with Suspension Chords and Inversions

How to make the five chord and tonic chord equalize.

Coming In For A Landing

When writing music, it is important to take your listeners on a journey. There are many paths to take musically, but the destination is usually known ahead of time because of the tonic. This is the note that all other notes revole around. In the C Major Scale, the note C is the tonic, but we should think of it as the “tonal center” because it’s what defines the roles of all other notes in the scale.

Think of a short melody as a little musical journey. You start somewhere and get moving. You can add more places to go in the form of chords. There are journeys to take in neighboring keys. In the end we have to end the journey.

So how can we arrive at our musical destination in an interesting way so that our listener can get a sense of arriving early? To do this we will ultimately use a chord form known as a V7sus4 or V7sus. We will also talk about Isus2 chords, inversions, and a little bit of voice leading so that we can see and hear how the V7sus4 can help us arrive at the tonic early.

The Authentic Cadence

Music is a lot like a language. We express ideas in a sets of sentences and end thoughts with punctuation. Music allows us to express a thought through sound and still tie off groups of thoughts with types of punctuation called cadences. Today we’ll use the authentic cadence to explore a coll anomaly within suspension chords.

An authentic cadence takes the fifth chord of a major scale and moves to the tonic chord. Below we have G moving to C in the C Major Scale in notation along with a chart. The chart lines up the notes in a G chord with the notes in a C chord.

You do not have to play G to C descending to make an authentic cadence. All that is required is moving from the fifth chord (V) to the tonic chord (I) in any direction. An authentic cadence is one of the strongest ways to resolve a phrase because the fifth chord, or V chord, is a dominant chord that uses specific notes of the Major Scale. In C Major, the note G is called the dominant as it has a dominating presence that supports and moves to the tonic note: C. The note B is the leading tone and is a half-step below the note C. This note leads us up to the tonic. Try singing do, re, mi, fa, so , la, and hang on ti. The leading tone is “ti” and following it with “do” is the tonic, which allows ti to resolve that tension you felt while hanging on that note. F is the sub-dominant in the key of C Major. While this note is not in the chord G, it is implied because the chord G uses G, B, and D as degrees 1, 3, and 5. The next degree to use is the seventh and here we have a ♭7 which is the note F. The sub-dominant always adds a sense of movement in music, but using the sub-dominant and leading tone together creates an interval, or distance between notes, called a tritone. A lot of tension is felt when the tritone is evoked. All of these factors helps the V chord hold a lot of dominating tension that can be resolved when moving to the I chord.

Applying an Inversion

Above we have the same cadence, but the notes of the V chord have been rearranged. In this case the 5th degree of G is in the bass and creates an inversion. Think of inversions as the same collection of notes, but in another order. In this example the second note after G, which is D, is in the bass. This is a second inversion of G.

If that is a little confusing then think of it in these steps.

G = G B D

G in first inversion = B D G

G in second inversion = D G B

The only note to watch for is the one that is in the bass. This allows B-D-G and B-G-D to both be G chords in first inversion. Second inversions of G can be D-G-B and D-B-G.

Above we can also see how this inversion of G moves easily to C. The note G is in both chords, so it simply remains. The note B moves up a half-step to C in a leading tone to tonic motion. The note D is a whole step away from C and E. Since the leading tone moved to C, it makes more sense that D moved to E. I just want to point out that there are many ways to voice G and C chords, so there may be times that D moves to C.

The Vsus4 Chord

Next up we have the same thing, but the G chord has become a Gsus4. In any chord, taking the third degree note and moving up to the fourth degree creates a sus4 or sus. This means to suspend the third upward. We can also suspend down to the second degree note and create a sus2, but we will stick with the sus4 for a good reason.

Gsus4 as G-C-D or in any inversion contains the tonic note: C. This is where the magic happens. By playing a Vsus4 to I we pre-arrive at the tonic but evoking the tonic note. Above you can see how the notes G and C are in both chords and only the note D needs to move. In this case the note D moves up to E, but again, it is good to know that D can move down to C in other applications.

V7sus4 to I

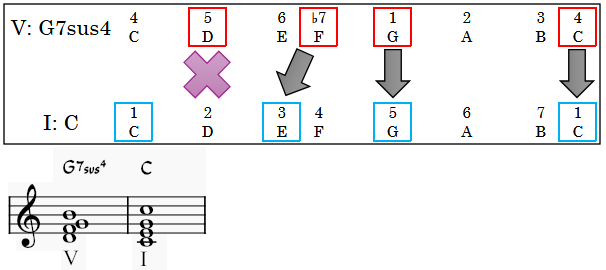

When we talk about “voice leading” in music we treat each note as a voice or singer. To help our singers out, we want to give them as little work as possible. Below we have G7sus4 in second inversion moving to C.

The singers for G and C have nothing to do. This is great because they have nothing to do other than sing their own notes. The singer for the F note can sing an E note. This is also good voice leading because the movement from F down to E is a half-step. The most movement you want is a “major third” or two whole steps.

The singer for the note D can take their note down a whole step to C. Another option would be to omit this singer and allow the C note that already exists to have the role of voicing the tonic note of C. This is where “voicing” comes in. We can take four voices in a G7sus4 singing D-F-G-C and follow it up with three voices singing C-E-G-C, or have three voices sing E-G-C. We can also end on three voices of C-E-G. It all depends on how the composer wishes to “voice” this movement.

The Implied Third

In G7sus4 the thired degree note of B is raised to the fourth degree of C. Since the third is literally suspended upward, the note C is felt like a B♯. This may sound like nonsense, but bare with me as this next little bit can be super technical.

If we take the third degree and raise it a half-step to become the fourth degree, then B is sharpened by a half-step, thus B becomes B♯. C is an enharmonic equivalent of B♯ and are note the same note. Yes, they share the same place on your instrument. Yes, the make the same sound from your instrument. And yes, the are different because when calculating the frequency of B♯ and C you will get two different values.

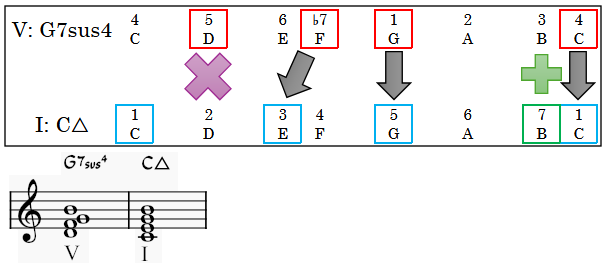

Regardless of the frequency, we can think about this in terms of suspension. If the third is raised a half-step and we feel that as a sus4, then we are feeling that the fourth degree wants to resolve down and become the third degree again. In this way, G7sus4’s C note is a ♯3. Following G7sus4 with C△ let’s the B♯ note (aka C) resolve down to B and act as the leading tone in C.

It’s kind of like saying to our singers that the one voicing C will do so in both chords, but needs to stand where our B note singer is for the first chord so they sound like a B♯. When C△ kicks in, the C note singer steps over to their proper position so that the singer who is only responsible for the B note can have their moment in the spot light. Using the notes D-F-G-C and no B for the first chord uses five voices, but one is silent. The second chord uses E-G-B-C, but no D. Again we have five voices, but one is still silent.

OK. The super technical part is over.

Equivalent Sus Chords

Now that we’ve talked about the V7sus4, inversions, and some voiceleading, it is time to get into the good stuff. Below we have Gsus4 and Csus2. Remember how we can use the same collection of notes and retain the chord as an inversion? Well, check out the notes in these two chords shown below.

Since Gsus4 and Csus2 use the same notes, we can treat them as the same chord. Not only does a Vsus4 allow us to arrive early at the tonic by using the tonic note as the fourth degree, but it is the tonic chord in a sus2 form.

Taking this a step further we can use G7sus4: G-C-D-F and substitute it with C△sus2: C-D-G-B. The notes G-C-D are in both chords and can be thought of as Gsus4 = Csus2. In G7sus4 we have an F and C△sus2 has a B. Remember how the fourth degree note or sub-dominant creates movement and the leading tone pulls us to the tonic? That’s exactly what happens between these remaining notes. F is “moving” us to C and B is “leading” us to C.

Above we have two sets of ii-V-I chord progressions. While the totality of the notes in G7sus4 and C△sus2 are note completely the same, try treating them as the V chord. One version uses the note F and moves us to C. The other version uses the note B and leads us to C. The beauty of this is that C is in both chords and lets us arrive early at the tonic.

Feeling The Landing

Below is an audio clip of the last example. This example is broken up into nine bars so that the G7sus4 and C△sus2 movements can be seen and heard easily. In the fourth bar, listen for G7 to give way to G7sus4 and arrive at C early. G7sus4 can be felt as a substitute for the I chord. Also listen for the note F to “move” us towards C. In C△sus2, listen for this to be a substitute for G7sus4 with a leading tone that pulls us to the note C throughout the eighth bar.

Thanks for reading and have fun swapping V7sus4 with I△sus2. If you have any questions or comments, then please let me know.